Californias Historic Highways

Stephen H. Provost

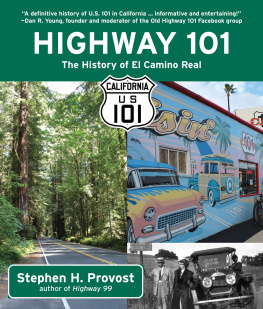

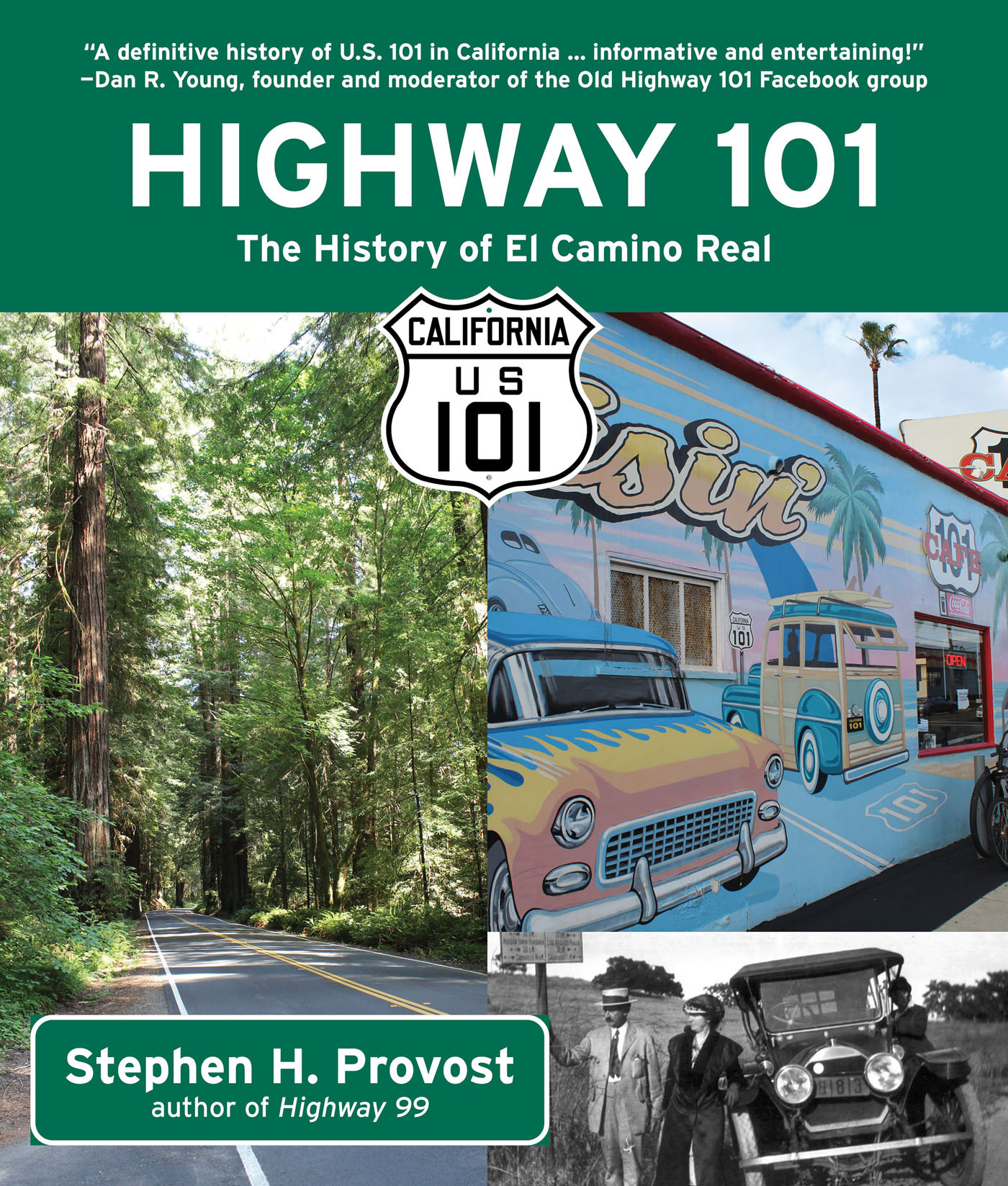

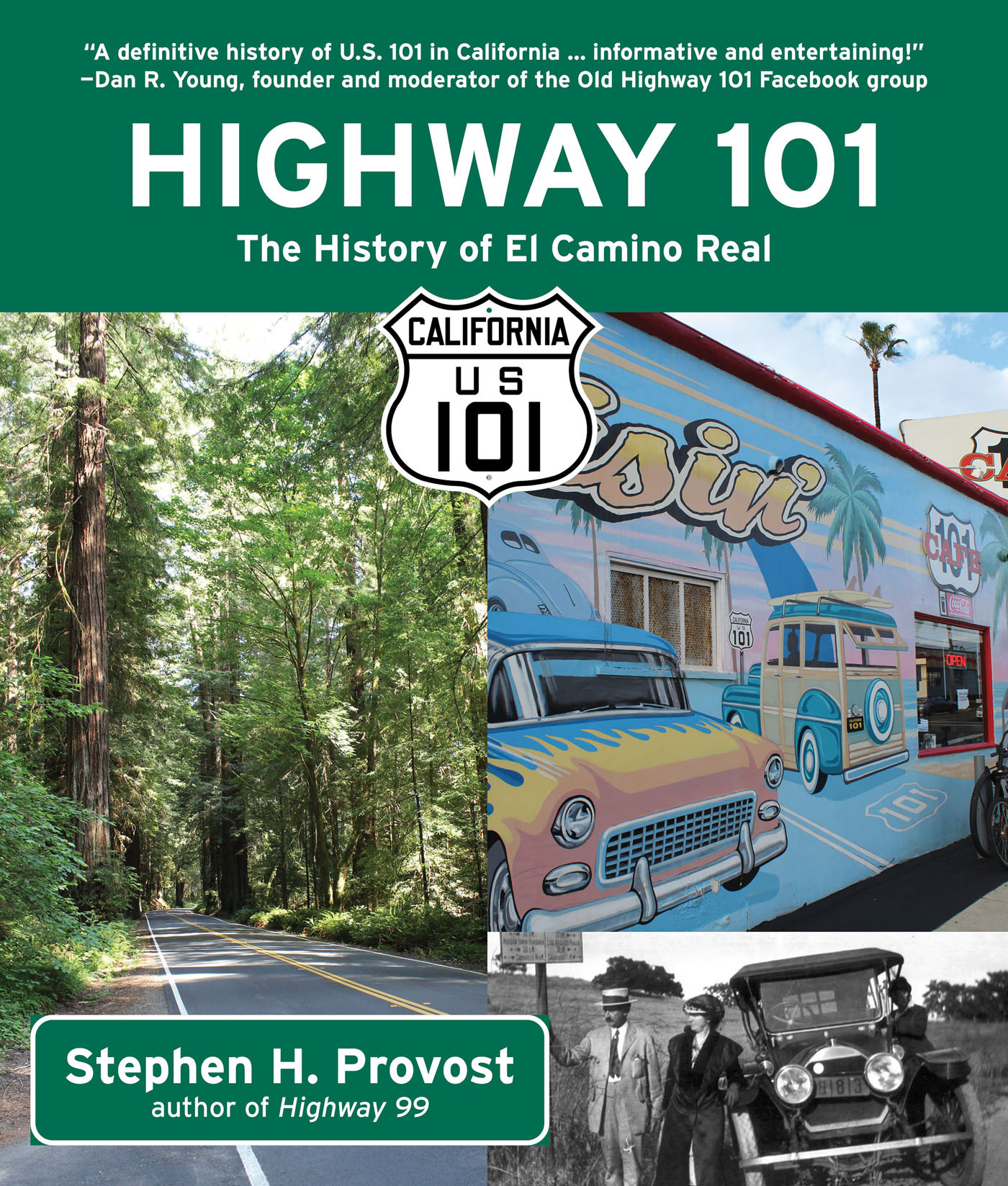

Highway 101: The History of El Camino Real

Copyright 2020 by Stephen H. Provost. All rights reserved.

All photos by author unless otherwise noted.

Book design by Andrea Reider

Published by Craven Street Books

An imprint of Linden Publishing

2006 South Mary Street, Fresno, California 93721

(559) 233-6633 / (800) 345-4447

CravenStreetBooks.com

Craven Street Books and Colophon are trademarks of Linden Publishing, Inc.

ISBN 978-1-61035-352-6

135798642

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data on file.

To the curious, the explorers, and the trailblazers

Contents

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

S everal people were instrumental in helping me make this work possible through their contributions, guidance, and support. Among them U.S. 101 historian Dan Young, who took me on a guided tour over the northern end of the highway, and of course, my wife and traveling companion Samaire Provost, who not only accompanied me on my photo trips up and down the state but served as my guide for the portion of Old 101 that passes through San Diego County, where she grew up.

INTRODUCTION

M y previous book, Highway 99: The History of Californias Main Street, took readers on a tour through the heart of California, down a road I traveled during my childhood. In 2012, I moved west from the San Joaquin Valley, where Id lived most of my life, to the California coast and began driving a different highway: U.S. 101.

It parallelsliterally and figurativelyold U.S. 99, but it has a history all its own thats just as rich and fascinating.

As with Highway 99, Ive explored the history of the road itself as well as the people and places along the way who supplied it with a unique identity: people like Walter and Cordelia Knott, founders of Knotts Berry Farm just a mile off the 101; Florence Owens Thompson, the iconic Migrant Mother in Dorothea Langes famous photo; Anton and Juliette Andersen, who started Pea Soup Andersens in Buellton; and Alex Madonna, who laid hundreds of miles of California highway and built the distinctive Madonna Inn along U.S. 101 in San Luis Obispo.

Up ahead, youll read about the signs along the highway, both porcelain and neon, and youll learn about how the oil industry helped define the road.

Ive followed a format similar to the one I used in Highway 99, dividing the book into two sections: the first topical, and the second a south-to-north tour of the road that will help you follow the modern route and retrace the old. Each of the chapters in Part II is named for what I considered to be the most recognizable stretch of highway in each area Ive covered, although there are often other names for each section.

So hop in your vintage Model T or your modern Chevy Malibu, buckle up, and enjoy a ride down memory lane, a.k.a. U.S. Highway 101.

The open road awaits.

PART I:

THE STORY OF OLD 101

BELLS, NO WHISTLES

H ow do you choose the path for a highway?

Its a question we may not think about as were rushing down the interstate, hurrying to get to whatever our destination may be: the office, a romantic dinner with our sweetheart, Christmas dinner at Grandmas house. But road builders had to think about it a lot at the dawn of the automotive age, when there werent any paved roads to speak of.

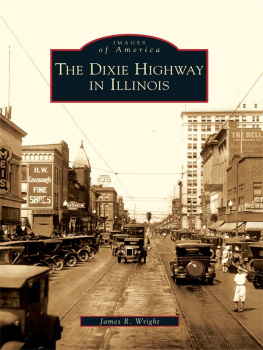

When they charted a course for the first primitive highways, they had their own agendas. Many of them were businessmen who had a stake in getting people to the front door of their restaurants or retail establishments. What better way to attract customers than to create a highway that ran right outside that front door? Thats what Carl Fisher, the brains behind Dixie Highway from Detroit to South Florida, did: He owned a lot of land in and around Miami, and he wanted to create a road that would bring snowbirds south for the winter.

In between, it would pass through established cities and towns, even if they werent exactly in a direct line from Point A to Point B. The result, Fisher admitted, was the equivalent of a four-thousand-mile wandering pea-vine.

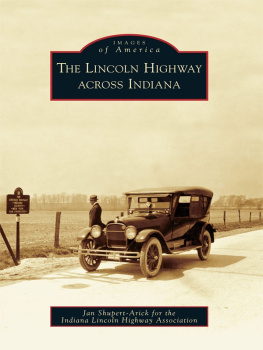

Where there were no towns to speak of, highways often followed the path of least resistance. If they had to cross mountain ranges, they went around hills and through canyons. This was necessary in an age when highways were carved out using steam shovels and mules pulling Fresno Scrapers. More sophisticated machinery was still a long way off in 1912, when the nation still had just 250 miles of concrete roadbefore asphalt replaced concrete as the material of choice in building a highway.

A couple stands near a decorative bell between Ventura and Calabasas on El Camino Real in 1906, two decades before the road was signed as U.S. 101.Public domain.

Even when technology advanced, the cost of upgrading roads was often prohibitiveat least at first.

Cy Avery, the Tulsa man who was the force behind the legendary Route 66, put it this way in a 1955 interview with the Tulsa World: Highways were routed around hills instead of through them, bridges were built eighteen feet wide, and section lines were followed despite the resulting right-angle turns because these made roads cheaper. There wasnt any big earth-moving machinery then, and we could build miles of road for what it would have cost to cut through one little hill. If we had made bridges two feet wider, we couldnt have built as many bridges. We had just so much money, and there was never enough.

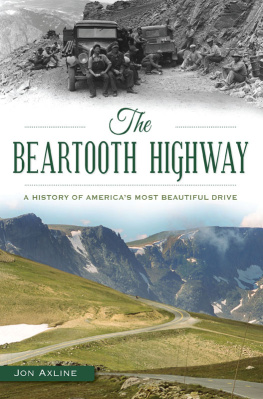

The Cuesta Pass north of San Luis Obispo shows what happened when road builders took the long way around. If you look off to the west as you descend the steep grade heading south toward the city, youll see a narrow band of concrete curled like a serpent around a low hill. This is a portion of the highways original alignment. Early builders couldnt blast their way through the mountains, so they went around them, creating horseshoe bends such as Dead Mans Curve, a similar segment of concrete that was once part of U.S. 99 between Grapevine and the Tejon Pass. As the name indicates, these were treacherous segments of road. At about 15 feet wide, they offered barely enough room for cars to share the road as they headed in opposite directions: The slightest miscalculation at an unsafe speed could send a vehicle tumbling over the edge.

Then there were the hairpin curves on the Conejo Grade along the Old 101 in Ventura County, winding steeply downhill from Thousand Oaks toward Camarillo. And on the San Juan Grade heading out of Salinas.

Elsewhere, highways snaked their way through canyons and riverbedswhich proved a problem during the rainy season, when flash floods, like the road builders, like the highway builders, followed the path of least resistance. Roads washed out. Vehicles got stuck. It was one heck of a muddy mess. Again, the Cuesta Pass offers a good example: The modern freeway is elevated and runs along the side of the mountain, the earth beneath it held in place above the canyon by a huge retaining wall. The original road, which extends from the concrete horseshoe bend described above, is a few hundred feet below, at the base of the canyon. When it was built back in 1915, one report counted 71 hazardous curves along its length through the canyon and over the pass.

Next page