The INVISIBLE EMPEROR

Mark Braude is the author of Making Monte Carlo: A History of Speculation and Spectacle. He has been a postdoctoral fellow and lecturer at Stanford University and was named a 2017-2018 Public Scholar by the National Endowment for the Humanities. His work has appeared in the New Republic, Los Angeles Times, Globe and Mail, and other publications. He lives in Vancouver with his wife.

ALSO BY Mark Braude

Making Monte Carlo:

A History of Speculation and Spectacle

The

INVISIBLE

EMPEROR

NAPOLEON ON ELBA

Mark Braude

First published in Great Britain in 2018 by

Profile Books Ltd

3 Holford Yard

Bevin Way

London

WC1X 9HD

www.profilebooks.com

First published in the United States of America in 2018 by

Penguin Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

Copyright Mark Braude, 2018

Book design by Marysarah Quinn

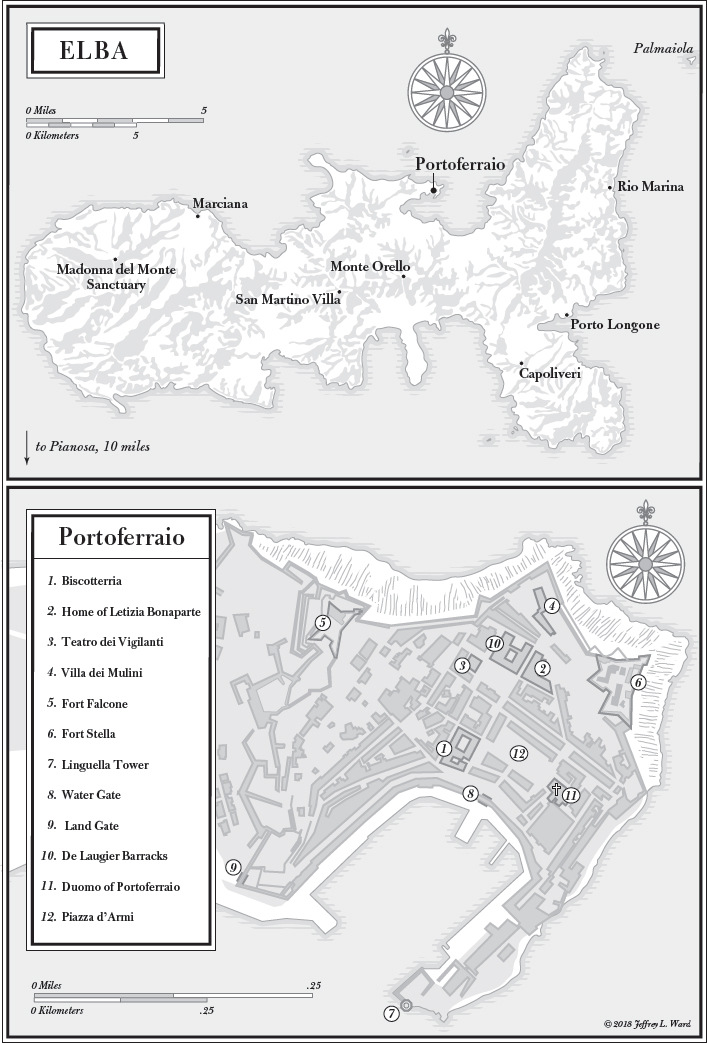

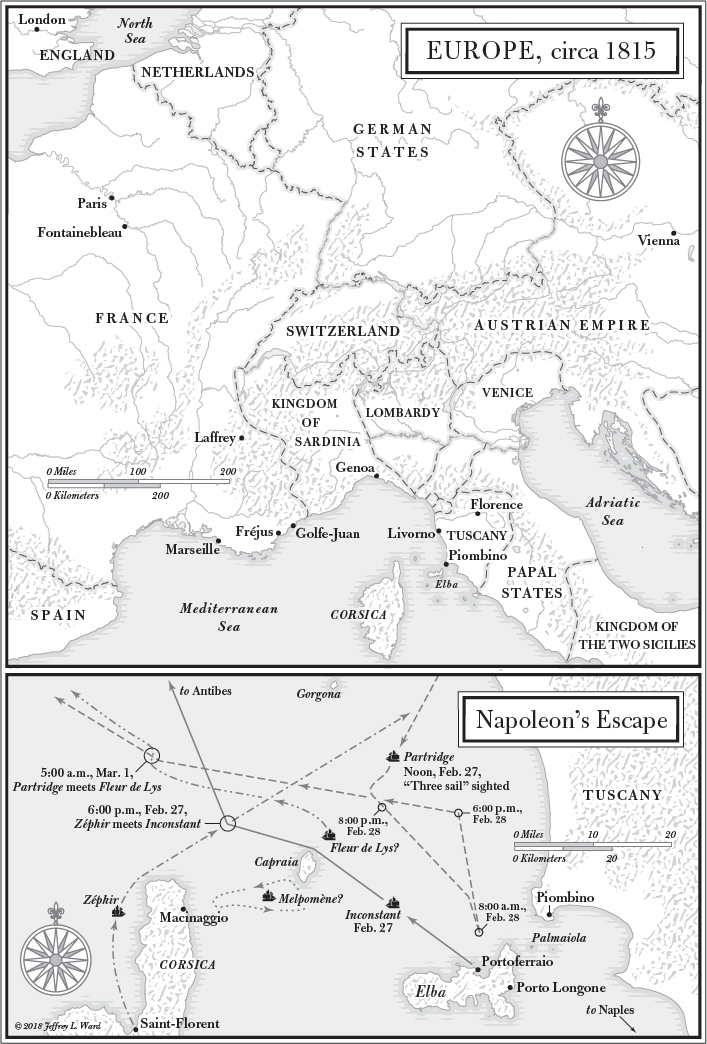

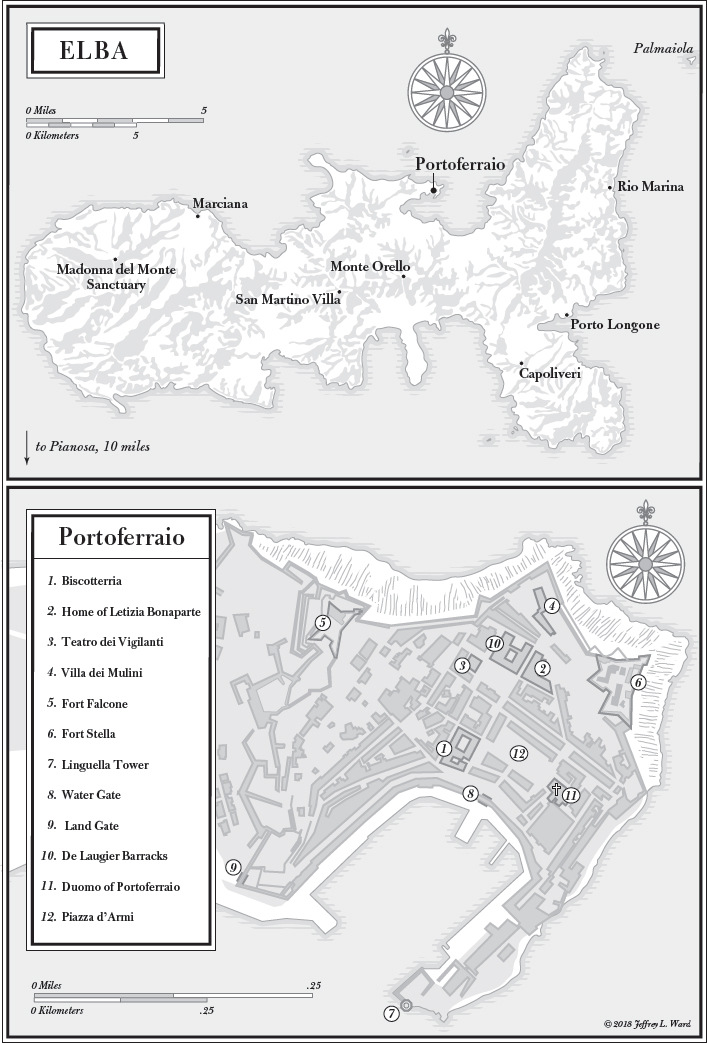

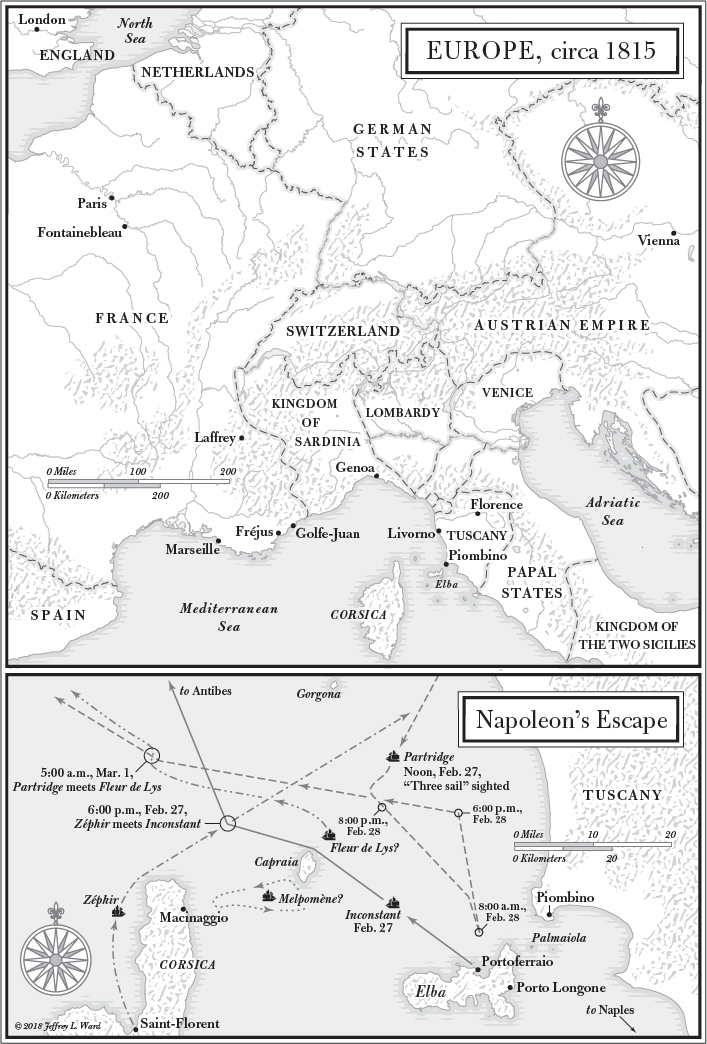

Map illustration by Jeffrey L. Ward

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 78125 802 6

eISBN 978 1 78283 336 9

FOR

Eleanor and Jeremy

Paradise is an island. So is hell.

JUDITH SCHALANSKY, Atlas of Remote Islands (2010)

Lucky Napoleon! This is the most beautiful island. There is no winter in Elba; cognac is threepence a large glass; the children have web feet; the women taste of salt. The Island I love, and I wish I were not seeing it in one of the seasons of hell.

DYLAN THOMAS, postcards and letters from Elba (summer 1947)

The Island of Elba, which a year ago was thought so disagreeable, is a paradise compared to Saint Helena.

NAPOLEON, on Saint Helena (February 1816)

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

IT ALL FELL APART quite quickly. From the towers of Notre-Dame and some of the higher rooftops, people watched through telescopes as invaders breached the outskirts of Paris on the night of March 29, 1814. Cossacks crouched round their campfires atop Montmartre, the sounds of their eerie music drifting down into the village below. They were toasting the death of the miller of the Moulin de la Galette, whose ravaged body was tied to one of the mills sails, or so went the rumor.

Parisians had good cause to be terrified just then. Fearing the populaces revolutionary potential as much as any foreign force, French officials decided against distributing arms en masse, even after troops failed to hold the enemy beyond the gates. This left the citys defense to the twelve thousand members of the Paris National Guard, facing a force nearly ten times larger.

Though the result would have been obvious to everyone going in, the spectacle was played out just the same. A British artist who lived in Paris, Thomas Underwood, recalled passing that bright spring day among fashionable loungers of both sexes at a popular caf on the boulevard des Italiens, sitting, as usual, on the chairs placed there and appearing almost uninterested spectators of the number of wounded French and prisoners of the allies which were brought in. Each side suffered roughly nine thousand casualties, making this the deadliest battle of 1814.

Napoleons subjects wouldnt soon forget his failure to appear in the capital alongside his generals. After a year and a half of fighting across much of Europe, an allied coalition led by Britain, Austria, Prussia, and Russia had driven French soldiers out of German territory and crossed into France. Instead of falling back to Paris, the obvious target, Napoleon had opted to dig in by the Aube River about a hundred miles east of the city, thinking he could cleave the attacking forces in two and defeat each half in succession. This had freed other allied troops to reach Paris largely unchecked.

Allied and French representatives had been trying to arrange Napoleons surrender for months. Joseph Bonaparte warned his brother that people would turn against him as soon as they realized he preferred prolonging war to making even a disadvantageous peace. But aside from a few brief moments of armistice, Napoleon had kept fighting, forever seeking the one dramatic victory that would allow him to negotiate from a position of strength. Having risen from artillery officer to general to First Consul to Emperor of the French on the promise of constant and glorious triumph, he feared he would be overthrown at the first sign that he was even considering bending to an opponents demands.

Napoleon had ridden for Paris as soon as he realized his mistake, switching out his exhausted horses for fresh ones borrowed along the way at intervals. But by the time he reached a posthouse just south of the city, around midnight on March 30, he was too late; a column of French cavalry had already arrived with news of the capitulation signed hours earlier by representatives of his trusted general and confidant, Marshal Marmont.

Realizing they could avoid a wider massacre by surrendering, Parisians had rushed into the streets to welcome the occupying soldiers with shouts of Down with the Emperor! and Death to the Corsican! Imperial eagles and Ns gave way to fleurs-de-lys, the stylized lilies of monarchy. People waved handkerchiefs of white, the traditional color of the Bourbon dynasty that had once ruled France. They brought down the statue of a laurel-crowned Napoleon that had topped the Colonne de la Grande Arme in the Place Vendme, built from melted-down cannons seized in the battle of Austerlitz, his gift to the city he had promised to make the most beautiful that ever existed.

After a short sulk by the side of the road, Napoleon retreated to the castle complex of Fontainebleau, nearly forty miles to the southeast, sending his aide-de-camp Armand de Caulaincourt to negotiate in Paris on his behalf.

At Fontainebleau, surrounded by his marshals, with soldiers bivouacked on the lawn and injured men recuperating in the outbuildings, he spoke of launching a counterattack on the occupied capital. He had about forty-five thousand troops at his disposal. But while his harangues drew cheers from the members of his Guard, beyond the castle confines such talk would have been dismissed as madness. Every village and town in Europe had been marked by the two decades of nearly perpetual war, with estimates of the death toll in the major conflicts since 1803 ranging from one to six million. Most of these deaths came not in the quick of battle but from festering wounds, or from dysentery, or from frost, or from being marched past the point of exhaustion. It was common to see mental patients forced out of asylums to free up space for incoming injured men.