Contents

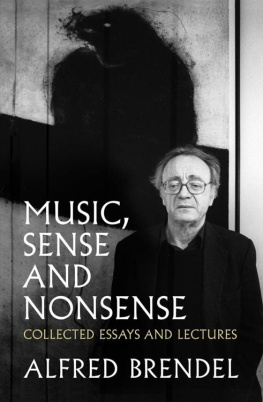

Utter nonsense! is how some of us would react when the firm ground of common sense starts swaying under our feet. For many, nonsense is something plainly negative, bound to make us surrender even more willingly to the blessings of sense. I would like to proceed differently and propose that it is our habitual entanglement with sense, our dependence on sense, our enslavement by sense that makes the pleasures of nonsense truly evident.

Sense is restricted, tied to rules, and finite. Nonsense ignores such shackles. It tells us that sense, the normal, rational, real and natural, lives by its limitations. It is obligatory. Even when nonsense respects certain rules, it remains a game, opposed to conventions and the customary procedures of reason. We savour the temporary escape from the real and habitual. At the same time, our awareness of reality is sharpened.

The early German Romantics were fond of nonsense. Novalis dreamt of poems without any sense and coherence. Similarly, Ludwig Tieck, the author of Puss in Boots, envisaged a book without coherence, full of contradictory nonsense. (It was the Swabian writer Justinus Kerner who provided, with his Reiseschatten, one of the most enticing examples.) Later, Edward Lear and Lewis Carroll became the quintessential nonsense poets for many. But in fact, nonsense poetry had already been alive and well in the Middle Ages, if not in ancient Egypt. Around 1200, the German minstrel Reinmar the Old, besides being a Minnesinger, was paying tribute to a poetry of the impossible (mendacious poetry, Lgendichtung). In a text from the fourteenth century, a fierce battle between a hedgehog and a flying earthworm is arbitrated by a floating grindstone.

Being liberated from rational restrictions, nonsense leads into the infinite. One enters, if so inclined, a religious sphere.

In this volume, a few nonsense texts translated from the Russian and German are interspersed between my own essays, which, if I can make such a claim, are doing their best to make some sense. As for the selection of nonsense, it is embraced here in the widest sense: there is the pure nonsense of Impossibilia a genre that exclusively handles the untrue and inconceivable as well as that of phonetic poems consisting of words that are devoid of meaning. But there is also the ample territory where sense and nonsense become entangled. After all, reality doesnt have to be excluded as long as it is altered, contradicted or compromised. Such texts tend to be comical unless they are written by the mentally ill. Sense and nonsense combined does it not represent the true condition of man? We can also spell it out paradoxically in Paul Valrys words: Two dangers threaten the world: sense and nonsense.

For Immanuel Kant, both music and laughter belonged to the realm of nonsense. One doesnt think of anything yet remains able to be vividly entertained. (The possibility of thinking in purely musical terms seems to have eluded him.) Delightfully, he calls genius dependent on whim (Laune), for whim has spirit (Geist) while order doesnt.

My selection of nonsense texts covers the whole gamut from poetic to the anti-poetic. It makes do without Carroll and Lear who are sufficiently known, as well as without Hugo Balls Karawane or Kurt Schwitterss Ursonate, canonic texts that were amply resurrected during the Dada centenary of 2016. Christian Morgensterns Das Knie remains the quintessential German nonsense poem. Charles Ambergs Tearing Out One of His Eyelashes, on the other hand, is the Dada cabaret song par excellence. Let me start with Daniil Kharms.

Kant, Reflexionen zur Anthropologie, 802 und 922.

translated by Alfred Brendel

THERE WAS A MAN

There was a man.

He owned a nose.

So he owned a nose that looked like a mouth.

So he owned a nose that looked like a mouth with two ears.

ANECDOTES FROM PUSHKINS LIFE

VI

Pushkin loved to throw stones. Wherever he saw stones hed start throwing them.

Sometimes he would warm to his task, standing there, crimson-faced, waving his arms, throwing stones simply appalling.

VII

Pushkin had four sons, and all were idiots. One of them couldnt even sit on a chair without constantly falling off. But even Pushkin himself had trouble sitting on a chair. As it frequently happened what a hoot! they were all sitting at the table. At one end, Pushkin fell off his chair, at the other end, his son. Quite intolerable.

THE INVENTOR ANTON PAVLOVI ILOV

The inventor Anton Pavlovi ilov sat down on a little bench in the Summer Garden (there is, in St Petersburg, a garden that bears this name, and the incident that I shall now describe occurred in the winter of 1933.)

All right, said Anton Pavlovi. Lets assume the lever is correctly attached and propels the bomb upwards.

As Switzerland was neutral during the First World War, Zurich became a refuge for artists, writers, intellectuals, pacifists, and young men of various nationalities avoiding conscription. In 1916 several of them decided to create a new kind of evening entertainment. They called it Cabaret Voltaire and established it at No. 1 Spiegelgasse, not far from the room occupied by an occasional visitor to the cabaret, Vladimir Ilich Lenin.

The group, which became known as Dadaists, consisted of two Germans (Hugo Ball and Richard Huelsenbeck), one Alsatian (Hans Arp) and two Romanians (Marcel Janco and Tristan Tzara), and was complemented by two women, the German Emmy Hennings and the Swiss Sophie Taeuber. They were soon joined by the Czech national Walter Serner. The youngest, Tzara, was twenty; Hennings, the oldest, thirty-one. All were united in their loathing of the war.

The initiator of the group appears to have been Hugo Ball. He was, like the majority of Dadaists, a writer but he had also worked for theatre and cabaret. As a pacifist he had had to leave Germany. Pale, tall, gaunt and near-starving, he settled with Emmy Hennings in Zurich, and was regarded as a dangerous foreigner. At the Voltaire, he declaimed his groundbreaking phonetic poem Karawane (Caravan) to the bemusement of the public. After a few intense months of Dada activity he parted company, turned to a gnostic Catholicism and died in the Swiss countryside, regarded as a kind of saint. His diary, Die Flucht aus der Zeit (The Flight from Time), remains one of the key accounts of Dadaism.

For Richard Huelsenbeck, noise, according to Hans Richter, seems to have been the most natural form of virility. Within Dada, he was the champion of provocation. A poet and journalist who subsequently travelled the world as a ships doctor and practised for a time in New York as a psychoanalyst, Huelsenbeck persevered with Dada and helped to establish its markedly different Berlin branch.

Among the artists of stature emerging from Dada, Hans Arp was perhaps the steadiest and most consistent. A friend of Max Ernst, Schwitters and Wassily Kandinsky, and a gifted poet, he was considered to be the most balanced member of the group, devoid of malice and envy, and endowed with a superior sense of humour. Sophie Taeuber, who was later to marry Arp, was a notable artist herself, teaching at the Applied Arts School in Zurich. She created marionettes, and was a member of Rudolf von Labans dancing school, which had established a new expressive style of dance. During her Dada appearances as a dancer, she had to wear a mask to disguise her identity.

In Tristan Tzara, calm and self-assured yet endowed with a thunderous voice, Dadaism had its most passionate advocate and its most tireless propagandist. Andr Breton called him a charlatan hungry for fame but was reconciled with him in 1929. Tzaras poems influenced Allen Ginsberg and William Burroughs, and a few of them were translated by Samuel Beckett. Like Arp, he subsequently became a Surrealist. Tzaras fellow Romanian Marcel Janco was described as a handsome melancholic, a ladies man who played the accordion and sang Romanian songs. He was a painter and sculptor who was to become a leading architect in Bucharest and Israel. He created masks for the Zurich Dadaists, and spoke, or rather shouted, simultaneous poems alongside Tzara and Huelsenbeck.