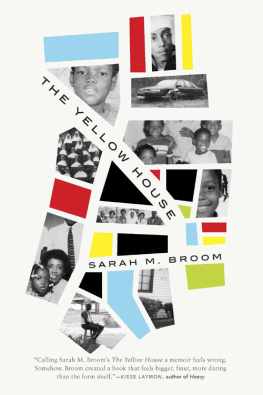

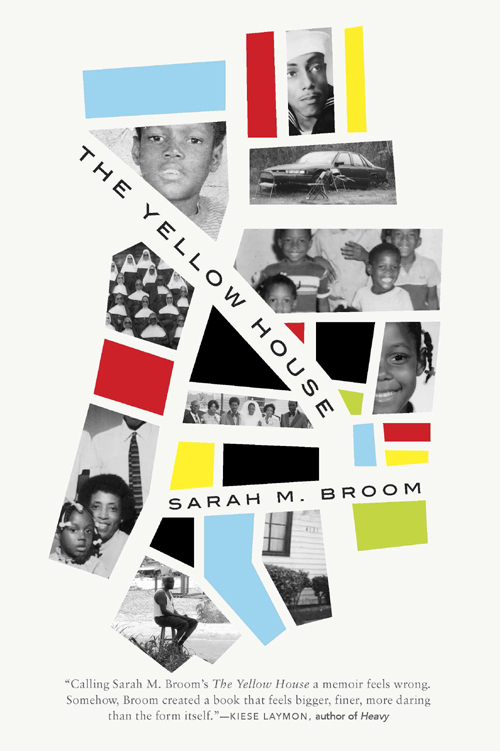

THE YELLOW HOUSE

Sarah M. Broom

Copyright 2019 by Sarah M. Broom

Cover artwork Alison Forner

Kei Miller, excerpt from The Cartographer Tries to Map a Way to Zion (Carcanet Press Ltd); Peter Turchi, excerpt from Maps of the Imagination: The Writer as Cartographer (Trinity University Press); excerpt from The Poetics of Space by Gaston Bachelard, translated by Maria Jolas, copyright 1958 by Presses Universitaires de France, translation copyright 1964 by Penguin Random House LLC. Used by permission of Viking Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved; Tracy K. Smith, excerpt from Ash from Wade in the Water. Originally from the New Yorker (November 23, 2015). Copyright 2015, 2018 by Tracy K. Smith.

Reprinted with the permission of The Permissions Company, Inc. on behalf of Graywolf Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota, graywolfpress.org; LeAlan Jones, Public Domain; Yance Ford, excerpt from the film Strong Island; John Milton, excerpt from Paradise Lost.

Public Domain; Unified New Orleans Plan, Public Domain; Lil Wayne, excerpt from AllHipHop.com interview in early 2006; Adrienne Rich, the lines from Diving into the Wreck. Copyright 2016 by the Adrienne Rich Literary Trust. Copyright 1973 by W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., from Collected Poems: 19502012 by Adrienne Rich.

Used by permission of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc; Joan Didion, excerpt from In the Islands from The White Album by Joan Didion. Copyright 1979 by Joan Didion.

Reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus and Giroux; Sam Hamill, excerpt from Narrow Road to the Interior: And Other Writings (Shambhala Classics).

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or permissions@groveatlantic.com.

FIRST EDITION

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in the United States of America

First Grove Atlantic edition: August 2019

This book was designed by Norman E. Tuttle at Alpha Design & Composition.

This book was set in 12-pt. Bulmer by Alpha Design & Composition of Pittsfield, NH.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available for this title

ISBN 978-0-8021-2508-8

eISBN 978-0-8021-4654-0

Grove Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

19 20 21 22 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

for three women, with love and heart

Amelia Lolo

Auntie Elaine

Ivory Mae

draw me a map of what you see

then I will draw a map of what you never see

and guess me whose map will be bigger than whose?

Kei Miller

To learn how to read any map is to be indoctrinated into that mapmakers culture.

Peter Turchi

From high up, fifteen thousand feet above, where the aerial photographs are taken, 4121 Wilson Avenue, the address I know best, is a minuscule point, a scab of green. In satellite images shot from higher still, my former street dissolves into the toe of Louisianas boot. From this vantage point, our address, now mite size, would appear to sit in the Gulf of Mexico. Distance lends perspective, but it can also shade, misinterpret. From these great heights, my brother Carl would not be seen.

Carl, who is also my brother Rabbit, sits his days and nights away at 4121 Wilson Avenue at least five times a week after working his maintenance job at NASA or when he is not fishing or near to the water where he loves to be. Four thousand fifteen days past the Water, beyond all news cycles known to man, still sits a skinny man in shorts, white socks pulled up to his kneecaps, one gold picture frame around his front tooth.

Sometimes you can find Carl alone on our lot, poised on an ice chest, searching the view, as if for a sign, as if for a wonder. Or else, seated at a pecan-colored dining table with intricately carved legs, holding court. The table where Carl sometimes sits is on the spot where our living room used to be but where instead of floor there is green grass trying to grow.

See Carl gesturing with a long arm, if he feels like it, wearing dark shades even if it is night. See Rabbit with his legs crossed at the ankle, a long-legged man, knotted up.

I can see him there now, in my minds eye, silent and holding a beer. Babysitting ruins. But that is not his language or sentiment; he would never betray the Yellow House like that.

Carl often finds company on Wilson Avenue where he keeps watch. Friends will arrive and pop their trunks, revealing coolers containing spirits on ice. Help yourself, baby, they will say. If someone has to pee, they do it in what used to be our den. Or they use the bright-blue porta potty sitting at the back of the yard, where the shed once was. Now, this plastic, vertical bathroom is the only structure on the lot. Written on its front in white block letters on black background: CITY OF NEW ORLEANS .

I have stacked twelve or thirteen history-telling books about New Orleans. Beautiful Crescent; New Orleans, Yesterday and Today; New Orleans as It Was; New Orleans: The Place and the People; Fabulous New Orleans; New Orleans: A Guide to Americas Most Interesting City. So on and so forth. I have thumbed through each of these, past voluminous sections about the French Quarter, the Garden District, and St. Charles Avenue, in search of the area of the city where I grew up, New Orleans East. Mentions are rare and spare, afterthoughts. There are no guided tours to this part of the city, except for the disaster bus tours that became an industry after Hurricane Katrina, carting visitors around, pointing out the great destruction of neighborhoods that were never known or set foot in before the Water, except by their residents.

Imagine that the streets are dead quiet, and you lived on those dead quiet streets, and there is nothing left of anything you once owned. Those rare survivors who are still present on the scene, working in those skeletal byways, are dressed in blue disposable jumpsuits and wearing face masks to avoid being burned by the black mold that is everywhere in their homes, climbing up the walls, forming slippery abstract figures underfoot. While this is going on and you are wondering whether you will find remains of anything that you ever loved, tourists are passing by in an air-conditioned bus snapping images of your personal destruction. There is something affirming, I can see, in the acknowledgment by the tourists of the horrendous destructive act, but it still might feel like invasion. And anyway, I do not believe the tour buses ever made it to the street where I grew up.