First published in 2010 by Oberon Books Ltd

Electronic edition published in 2013

Oberon Books Ltd

521 Caledonian Road, London N7 9RH

Tel: +44 (0) 20 7607 3637 / Fax: +44 (0) 20 7607 3629

e-mail:

www.oberonbooks.com

Copyright Neil Bartlett and Handspring Puppet Company 2010

Neil Bartlett and Handspring Puppet Company are hereby identified as authors of this play in accordance with section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The authors have asserted their moral rights.

All rights whatsoever in this play are strictly reserved and application for performance etc. should be made before commencement of rehearsal to The Agency (London) Ltd., 24 Pottery Lane, London W11 4LZ (). No performance may be given unless a licence has been obtained, and no alterations may be made in the title or the text of the play without the authors prior written consent.

You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or binding or by any means (print, electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

PB ISBN: 978-1-84943-100-2

E ISBN: 978-1-8494-3910-7

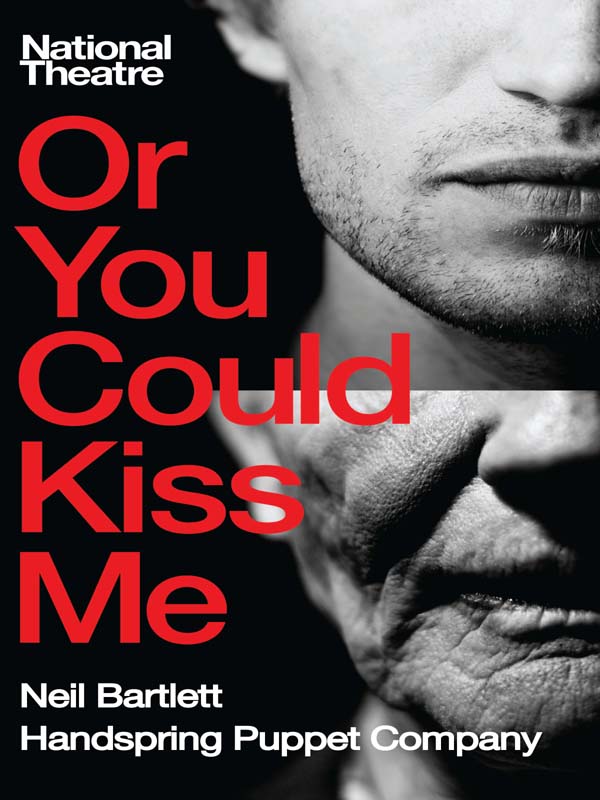

Cover photographs by www.istockphoto.com

Cover design by Charlotte Wilkinson

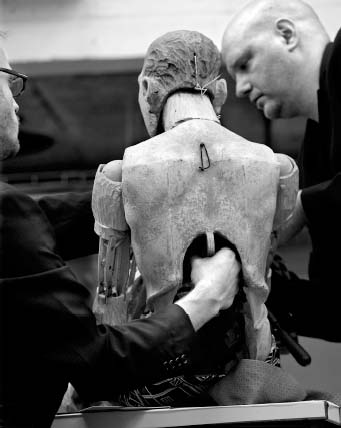

Photographs on pages 7, 8, 12 and 19 copyright Simon Annand Photograph on page 17 copyright Adrian Kohler

Lyrics on pages 54-55, What Are You Doing The Rest Of Your Life. Words and Music by Marilyn Bergman, Alan Bergman and Michel Legrand 1969, Reproduced by Permission of EMI Music Publishing Ltd, W8 5SW.

eBook conversion by Replika Press PVT Ltd, India.

Visit www.oberonbooks.com to read more about all our books and to buy them. You will also find features, author interviews and news of any author events, and you can sign up for e-newsletters so that youre always first to hear about our new releases.

Contents

WRITING SILENCE

AUTHOR AND DIRECTOR NEIL BARTLETT

REFLECTS ON THE GENESIS OF THE PLAY

What is a script, exactly?

Often, the answer to that question is simple; its the words. But equally often, the answer is less clear. In many kinds of theatre (pantomime, performance art, physical theatre not to mention ballet or musicals or opera) words alone can never provide a complete guide to any would-be performers, or to the audience. Even in a straight play, a category of western theatre where the words of the author are usually considered the primary determinant not only of what occurs on the stage but of what it all really means, words are still only the tip of various kinds of unspoken icebergs. Even in the most written of theatre events in, say Wildes The Importance of Being Earnest, Pinters No Mans Land or Racines Athaliah (to pick three plays which have only one thing in common, namely that the words are peerless) what we feel and see is happening to those people up there under the lights is just as important as what we can hear them saying.

Which is all by way of a preamble to saying that this particular script presented me with a very particular challenge as a writer for the theatre. Since the commission was to create perhaps a better word in this context than write a theatre piece for puppets, I had to acknowledge right from the start that this was going to be a text in which the words would have a subordinate or tangential role in communicating meaning. Basically, silence not speaking was always going to be the main event. This is because (to state the obvious) puppets may be able to do some things on stage more conveniently than actors ever could like swimming across the stage in mid-air, for instance but they can never, ever express themselves by speaking dialogue. The puppeteers can talk for them, to them, about them, and even across them, but that is not the same thing as the puppets themselves speaking. When puppets are on stage, whatever words are used are only ever there to provide a context for or guide to their essential silence. That is where their real (and often uncanny) power lies. It is also true (I have found, in the course of my work with the company on Or You Could Kiss Me), that a puppets action the life given it by the puppeteers is in some strange sense always qualified by and even given its true meaning by its essential stillness, its natural immobility. This is why, perhaps and this is, appropriately, hard to put neatly into words the situations in this play (ranging from the embarrassing to the terrifying) have all turned out to be unspeakable; that is, situations in which men find themselves rendered at best inarticulate and at worst speechless. And I suppose it is also why the elephants in the various rooms and landscapes of this play are the ones in the face of which we must all eventually fall silent: lust, love and death.

This play, despite its conventional billing, and although it did involve me spending hours alone in my study typing, was not authored in a conventional way. The process began with a chance meeting over a canteen cup of tea during rehearsals of the first run of War Horse at the National Theatre in London. I was introduced to Adrian Kohler and Basil Jones (the founders of Handspring Puppet Company) by my colleague Rae Smith, the designer of War Horse and now, our collaborator on Or You Could Kiss Me. Adrian and Basil knew my work as a writer of novels, but were unaware that I worked in the theatre. We started talking, got excited about the idea of working together, and, one conversation in another caf later, came up with a plan. In contrast to the epic scale of War Horse, the new piece was to be small-scale, intimate, in a contemporary setting, performed using human puppets instead of animals and (crucially) with Adrian and Basil themselves performing, as lead puppeteers. Then, in the privacy of several emails, we talked more. Mostly about very personal things (things which had happened to us in hospitals, in parked cars, on rocks, on squash courts and in bedrooms and on the telephone), but sometimes about the very different times and places we had lived in during the 1970s and 1980s they in South Africa and I in London. Out of our conversations I proposed transforming these autobiographical anecdotes into a fiction: a fiction whose unlikely spine would be a fragment of text I had been carrying in my mental back pocket ever since I was a bookshop-haunting adolescent Ovids unforgettably mysterious description, in the seventh book of his Metamorphoses, of the transformation (that word again) and death of Philemon and Baucis two lovers who have spent their entire lives together. On the basis of this back-of-an-envelope proposal, the National and its Studio encouraged and allowed us to do two things: to spend ten days in South Africa visiting possible actual locations for such a half-documentary, half-mythical story; and then another ten days with some puppeteers and some mock-ups of the proposed puppets, back in London, trying out some ideas.