One

THE RISE OF AN AMERICAN SPA CITY

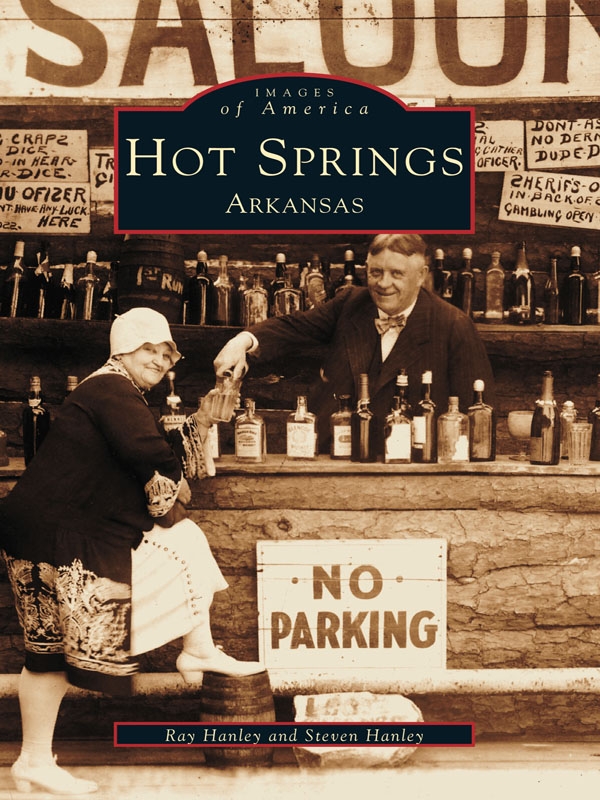

The grand future that had been envisioned for Hot Springs around the middle of the 19th century suffered a major setback with the coming of the Civil War. The areas able-bodied men marched off to battle, and bushwhackers burned much of the town. All but a tiny handful of the towns citizens fled the area, many going to Texas. However, Hot Springs would revive after the war, for the draw of the springs brought back residents and those intent on developing a resort around the geological wonders.

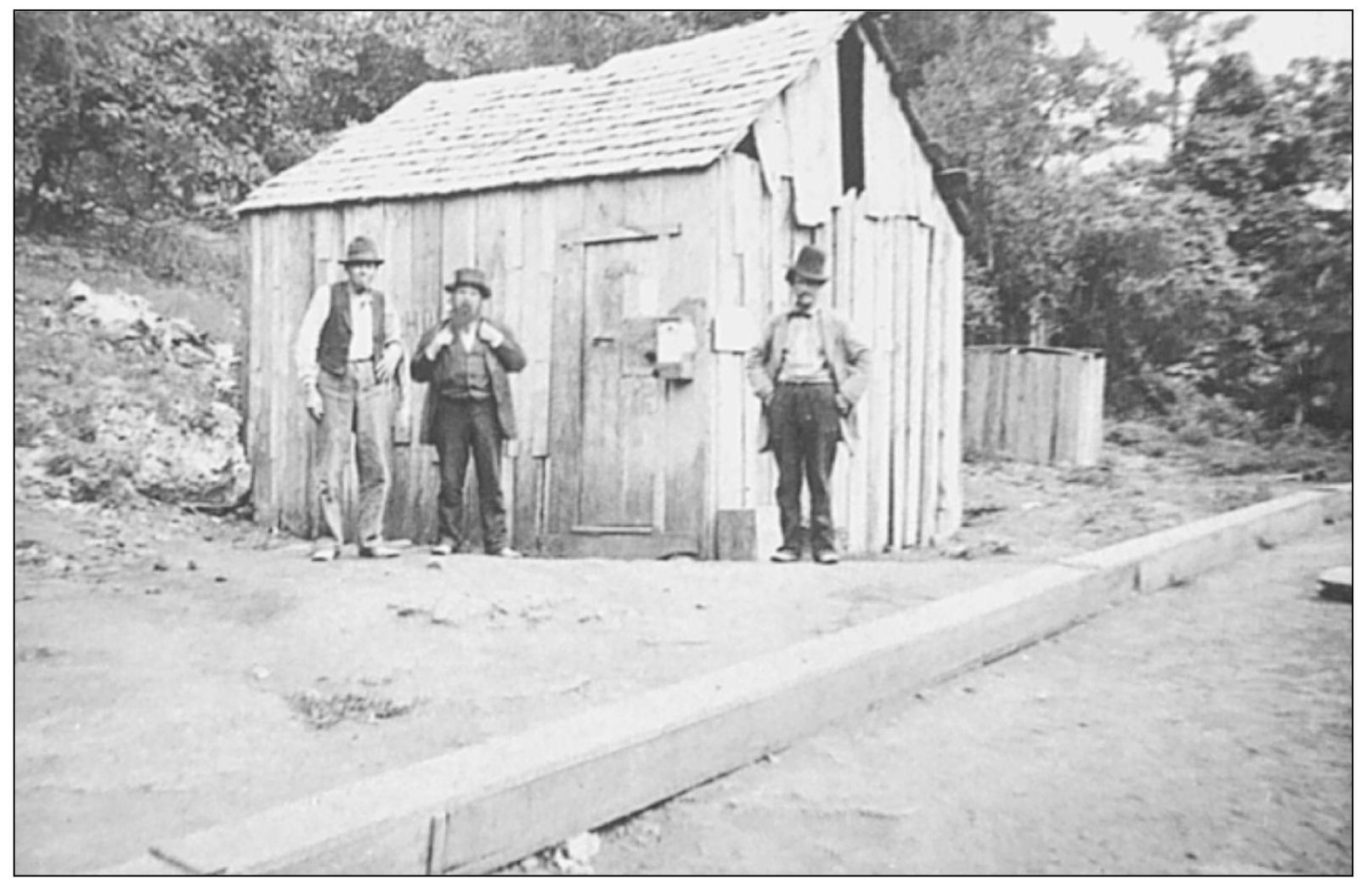

In the first few years following the Civil War, development around the springs was often crude and unregulated. Some bath houses were little more than rough shacks, often built directly over the springs, as seen in this c . 1875 stereoscope card. Concerned about unregulated development and questionable claims on surrounding lands, the federal government took the issue to the United States Supreme Court; in 1876 the Court nullified the competing claims and firmly established government ownership of the springs, thus insuring protection of the resources and orderly future development.

(Photo courtesy of Arkansas History Commission.)

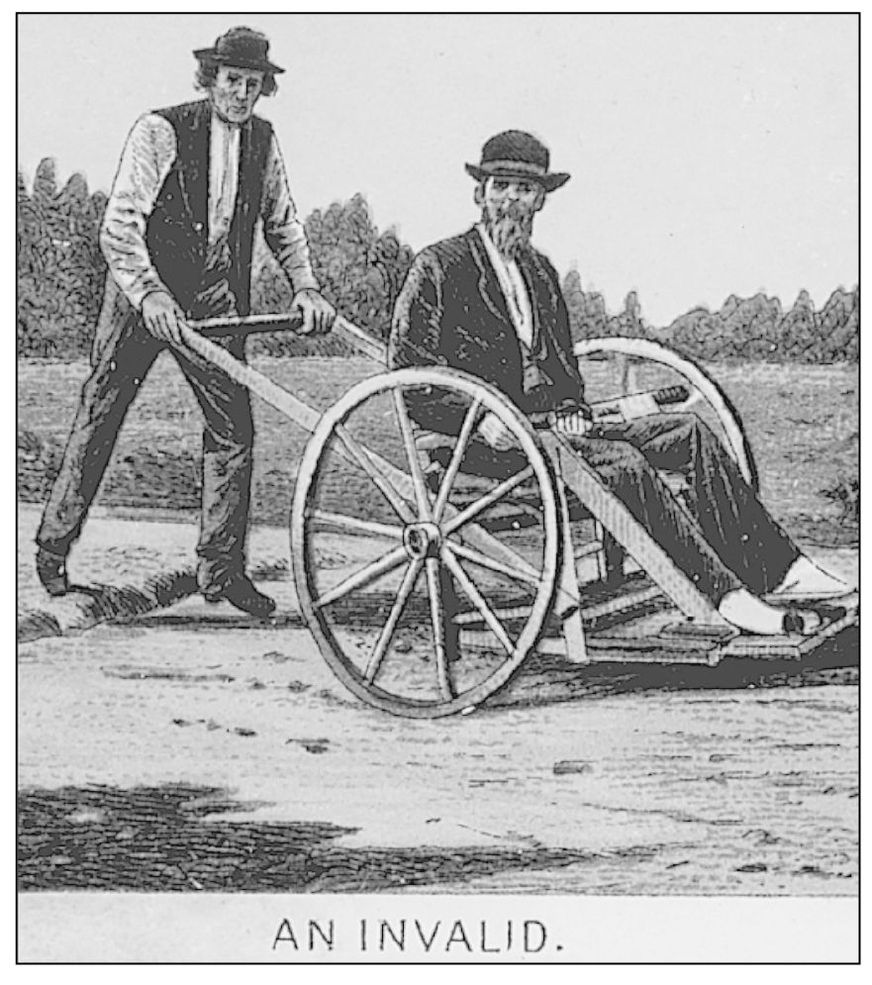

During the 1870s transportation into Hot Springs moved along rough roads that were improved only slowly, yet the sick and lame began to come in great numbers. One visitor described the scene around one open spring as follows: Here may be seen at all times of the day, but more especially morning and evening, the halt, the lame, the blind, some with contracted or crooked legs, or arms, others with a stiff knee, ankle or arm, enlarged or swollen joints, gout, skin diseases, boils, tumors, syphilitic affections, etc. An invalid is shown here being wheeled to a spring in a crude cart modified to serve as a wheelchair.

(Courtesy of Arkansas History Commission.)

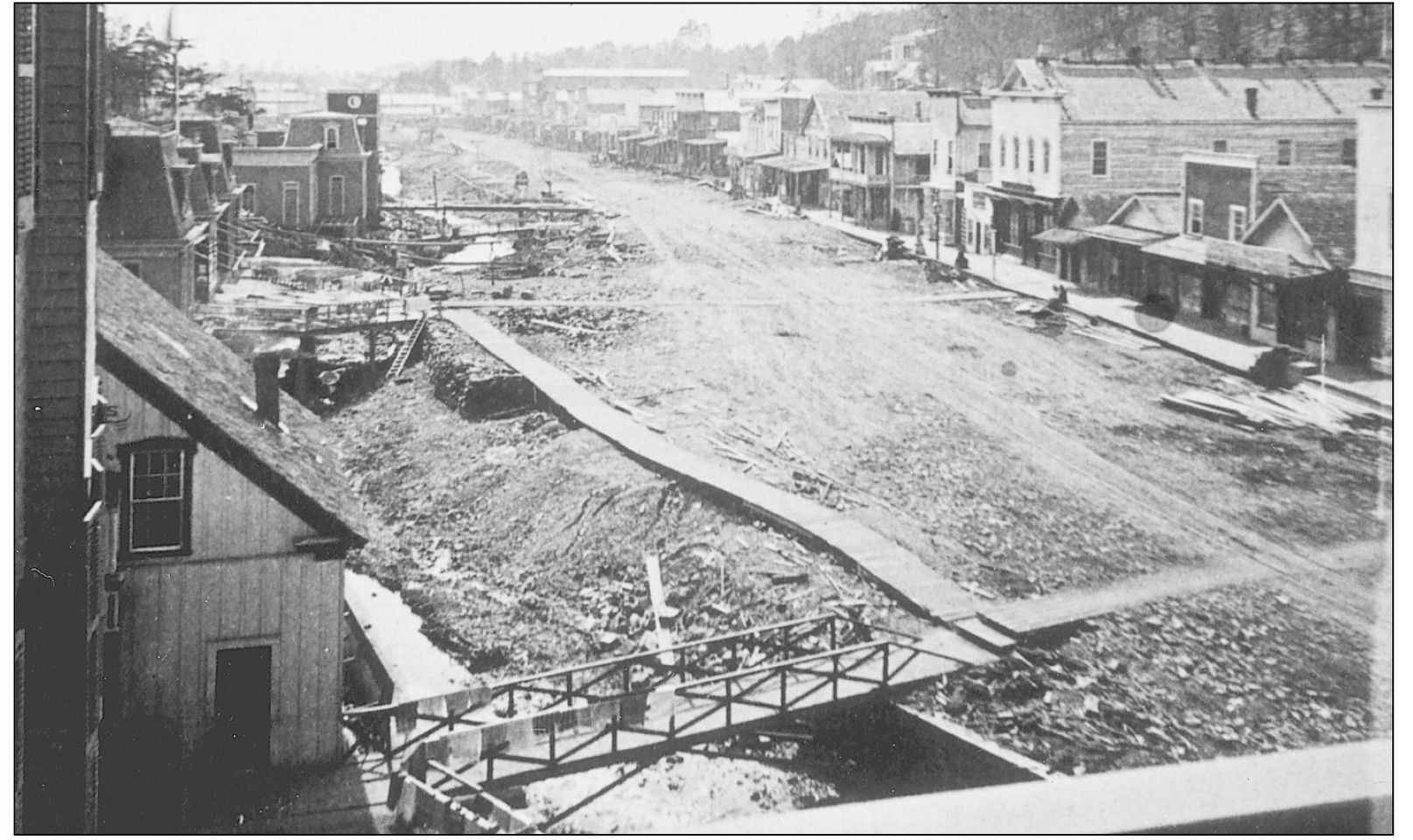

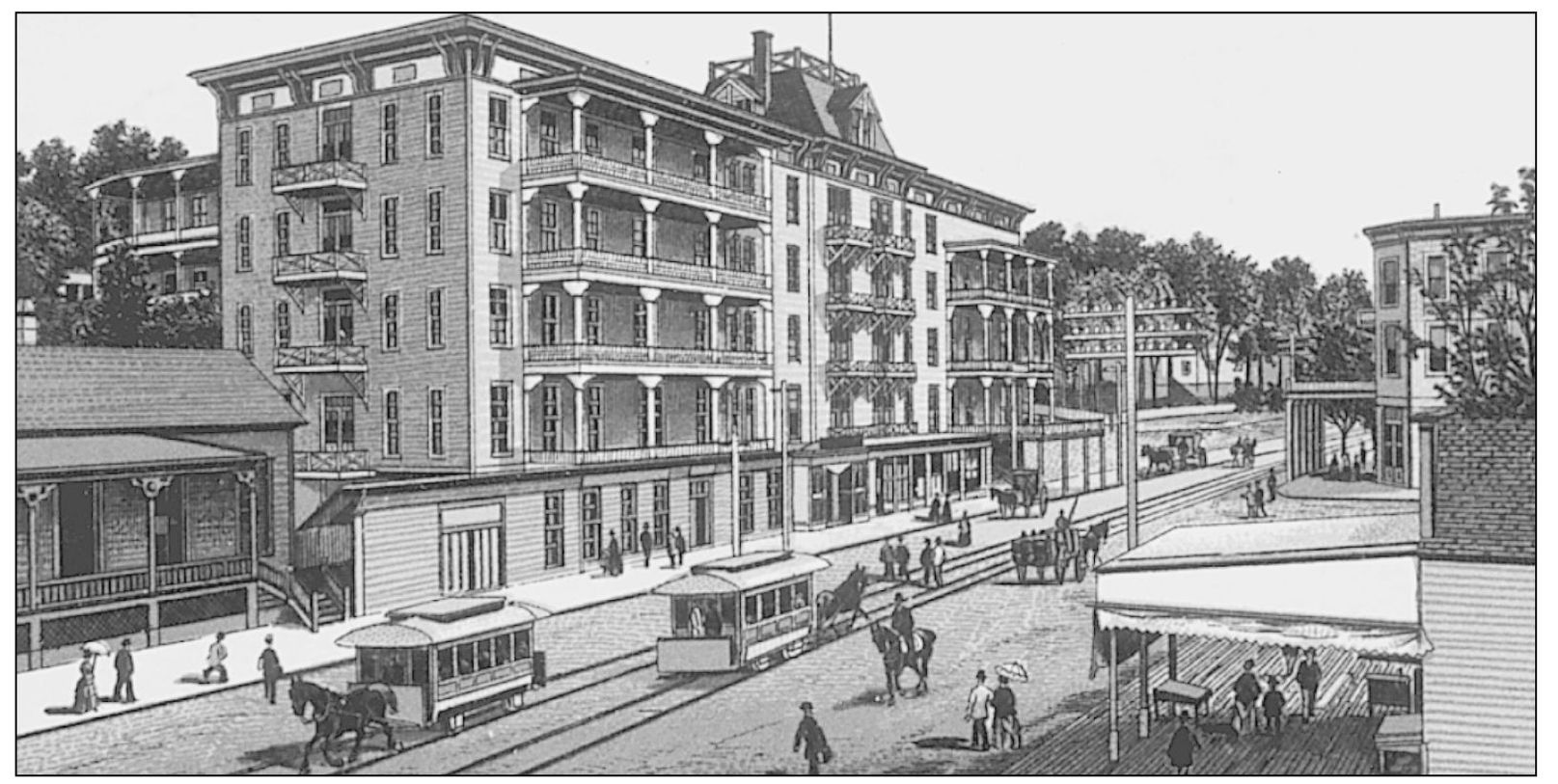

Central Avenue, known initially as Valley Street, was the heart of the main business and bath house district. The muddy thoroughfare was lined with frame structures to host the visitors that began to come in the 1870s. Hot Springs Creek, seen to the left of the road in this view, was an open ditch that often drew criticism from visitors, such as this penned by a New Yorker in 1876: When I add that there must be millions of pigs of all sizes and colors running at large, you can understand how unpleasant pedestrianism must be. Hot Springs Creek runs along the valley and crosses the road a least a dozen times in a mile, there are no bridges except foot bridges. In the mid-1880s the creek was covered over in the manner of a storm drain, creating a broad walkway running in front of the bath houses. This c . 1880 photo was taken from the one of the porches of the Arlington Hotel.

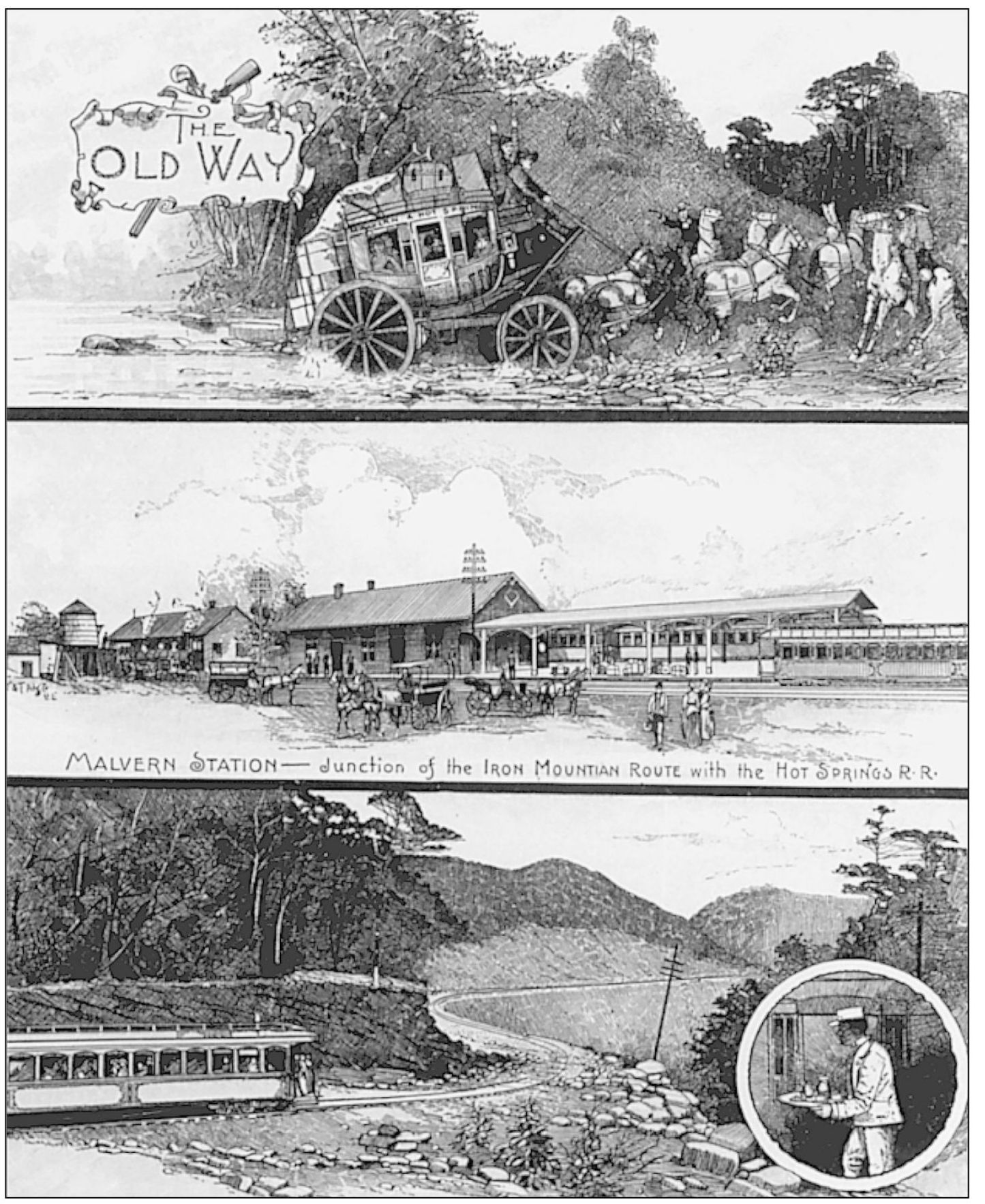

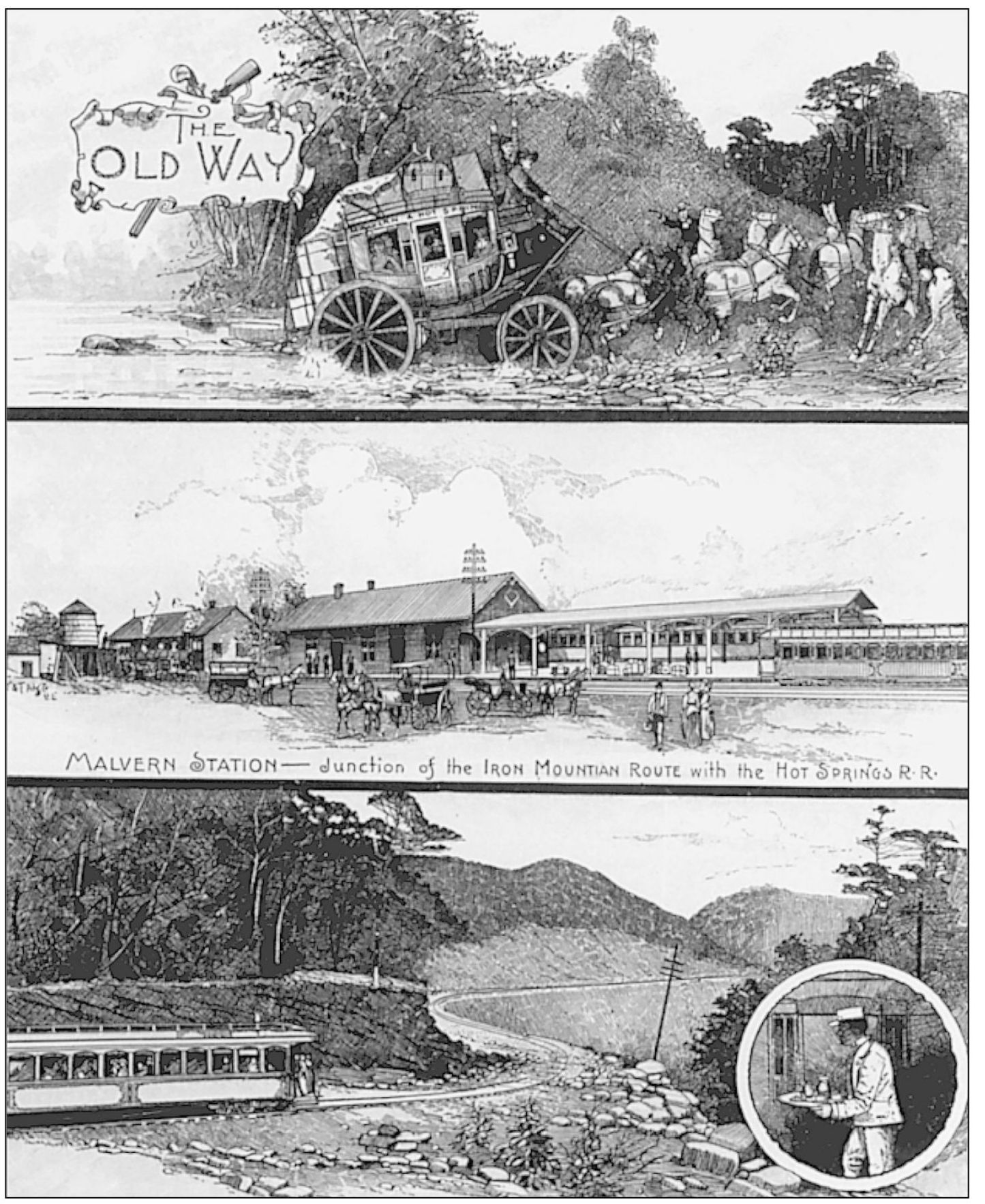

Travel into Hot Springs was rough and hazardous for decades, with stage travel beginning around 1836. By the 1870s visitors could come by train as near as Malvern, some 20 miles distant, but still had to switch to a stage for the jarring ride over a rough mountain road. Stage robberies were a particular hazard; at least one of these was thought to have been committed by Jesse James. One complaining visitor expressed hope in 1873 that before another year the iron horse with its shrill whistle would be heard throughout these valleys and mountain tops. In 1874, a wealthy northern robber baron named Diamond Joe Reynolds made this wish a reality. He had come to Hot Springs for the treatment of his rheumatism and vowed to replace the stage with a train, for he intended to return to Hot Springs often and in the comfort he could afford. Reynolds built a narrow gauge railroad from the depot at Malvern (center picture). Travelers bound for Hot Springs then left their large Pullman coaches for the smaller but richly appointed narrow-gauge railcars seen in the bottom drawing. Officially the line was called the Hot Springs Railroad, but to most it was the Diamond Joe.

(Courtesy of Arkansas History Commission.)

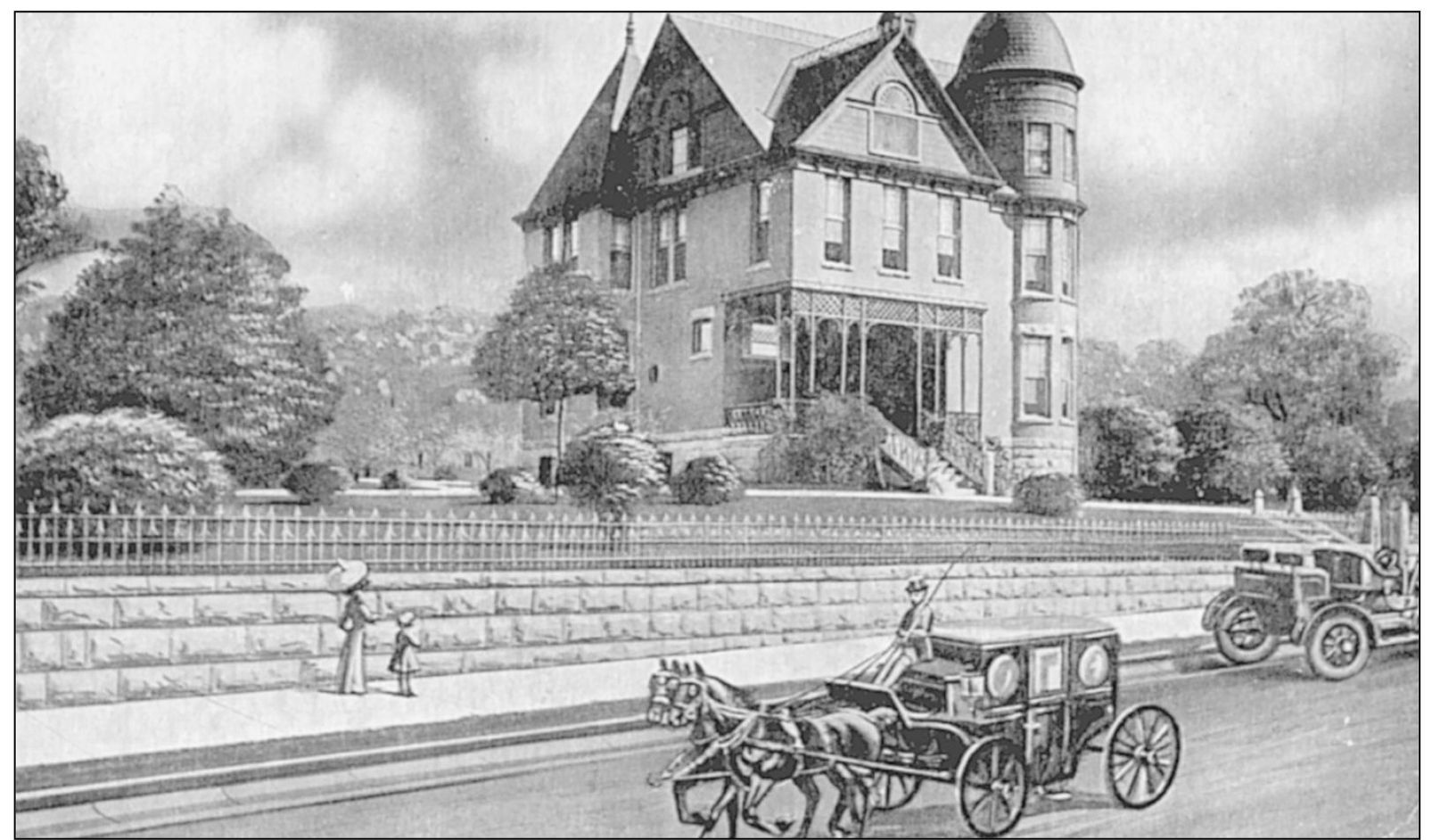

The Diamond Joe Sanitarium, named for the railroad baron, was operated at 313 Cottage Street by Dr. and Mrs. J.W. McClendon, who also lived in the facility. One of several sanatoria in the city, such a business was a cross between a hotel and bath house. It offered lodging and bathing, with the implication of greater medical benefits due to the physician on-premises. Dr. McClendon was elected mayor of Hot Springs in 1913, the same year the building was destroyed in a fire that ravaged 50 blocks of the city.

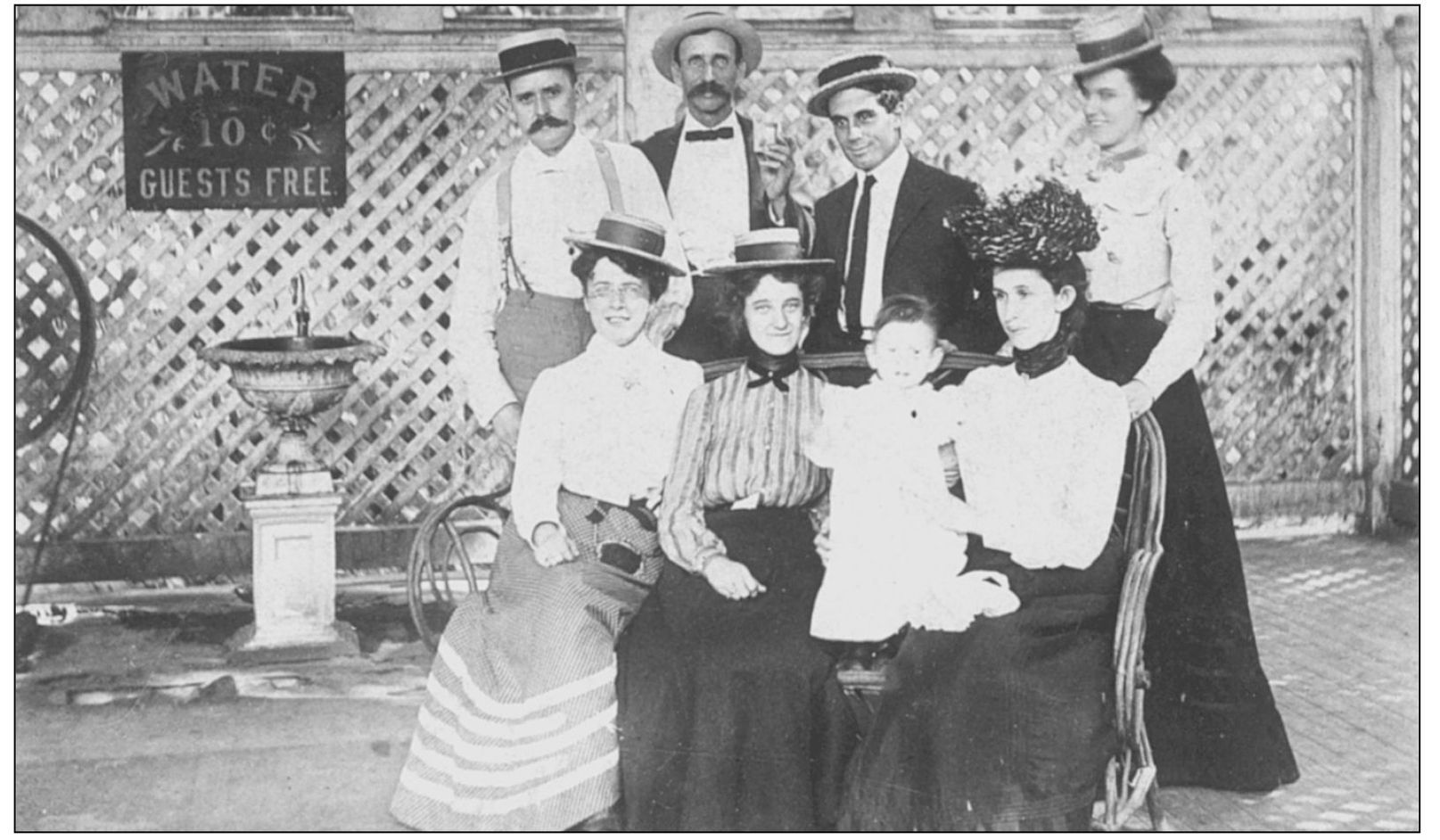

Visitors to Hot Springs came both to bathe in the water and to drink it, ascribing healthful benefits to both uses. This group was photographed around 1890 on a visit to Arsenic Spring at 103 Mount Ida Street. The man in the center is holding a glass of water taken from the fountain to the left. Arsenic Spring has been used since before the Civil War and may still be visitedthe business is not closed.