One

GETTING AROUND TOWN

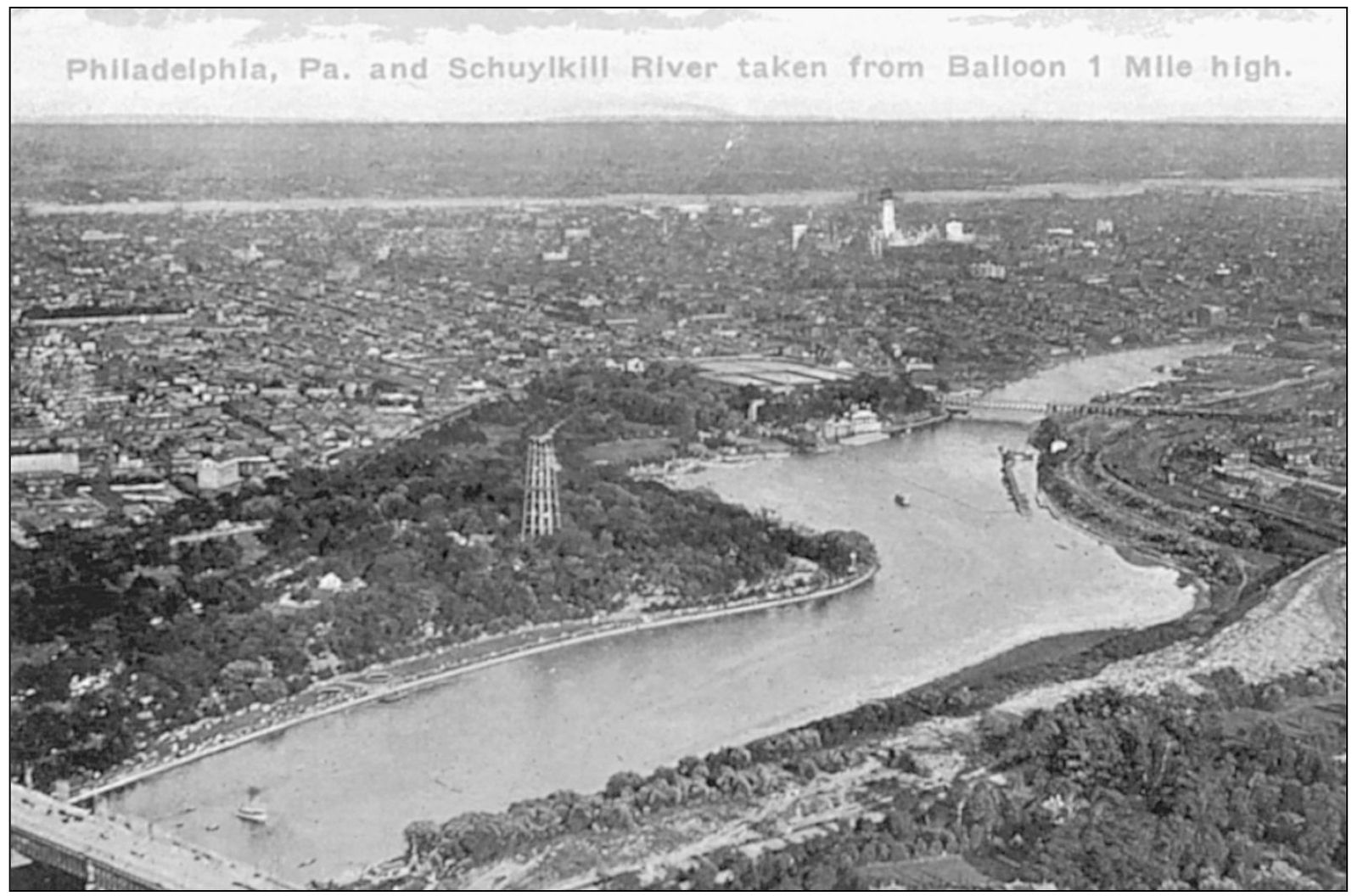

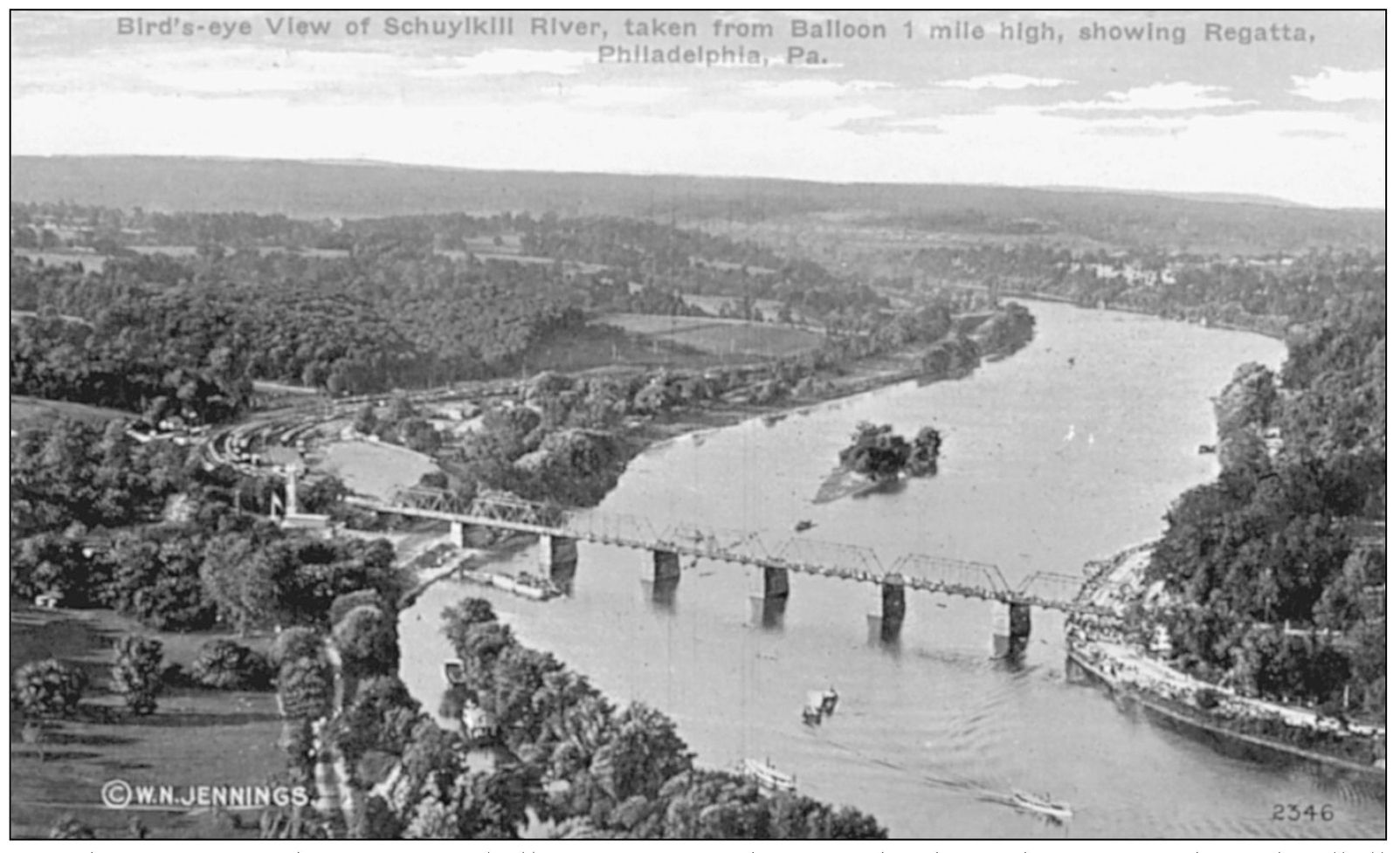

Visitors came to Philadelphia for many reasons during the first quarter of the 20th century. Some came for business, others for pleasure. Many recorded their visit through postcards. Sent to Michigan from Philadelphia in 1913, this postcard was one of a series that featured views of the city as seen from a balloon floating one mile above the landscape. Taken by William N. Jennings on the Fourth of July in 1893, the original photographs were the first aerial images of the city ever recorded. Fairmount Park and the Schuylkill River filled most of this postcard, giving the city a far less urban appearance than was really the case. In reality, Philadelphia had grown to be one of the worlds largest cities by the beginning of the 20th century. Between 1890 and 1930, the number of residents more than doubled as waves of immigrants poured into the city. Philadelphia had also become a manufacturing and industrial giant.

Another image in the Jennings balloon series of photographs showed a view of the Schuylkill River with a regatta in progress. While this postcard would also lead viewers to assume that Philadelphia was a small town nestled in a pastoral setting, the reality was much different. Other views in the aerial series presented views of a densely populated metropolitan area.

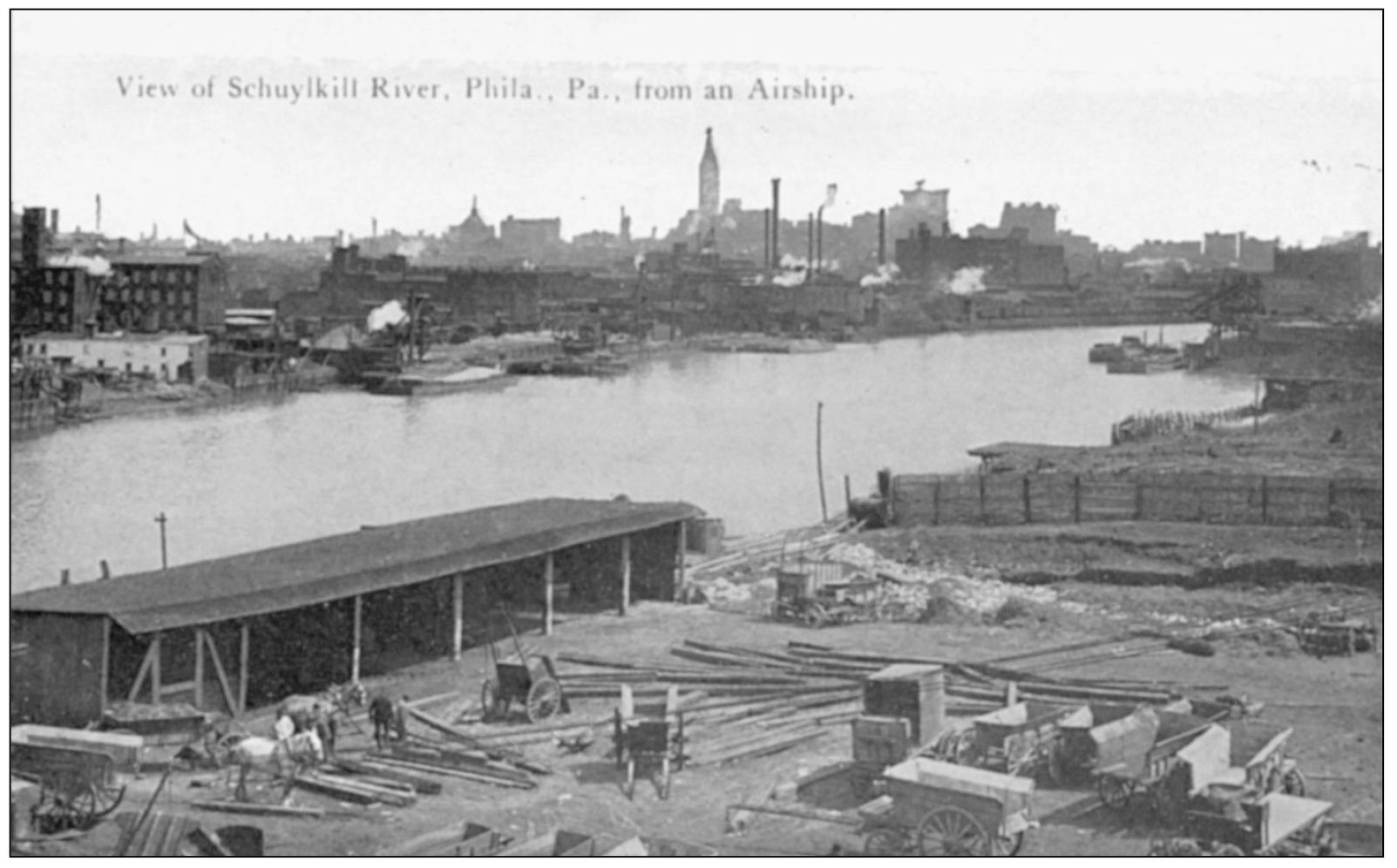

This view of the Schuylkill River and surrounding docks showed the working rather than recreational role that the waterfront played in the life of the city. Taken from an airship rather than a balloon, the image also showed the growth of the city with the recently completed City Hall in the background.

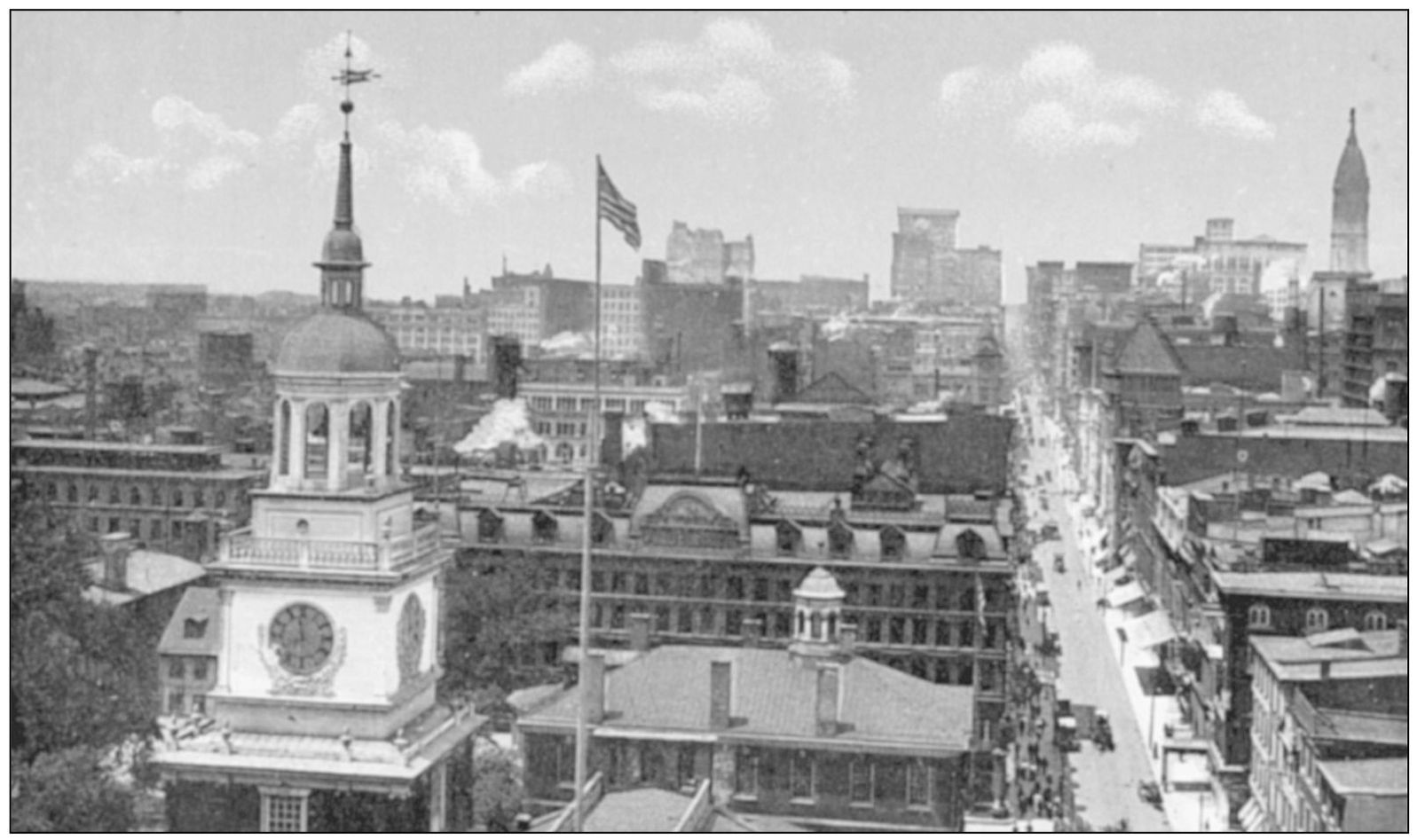

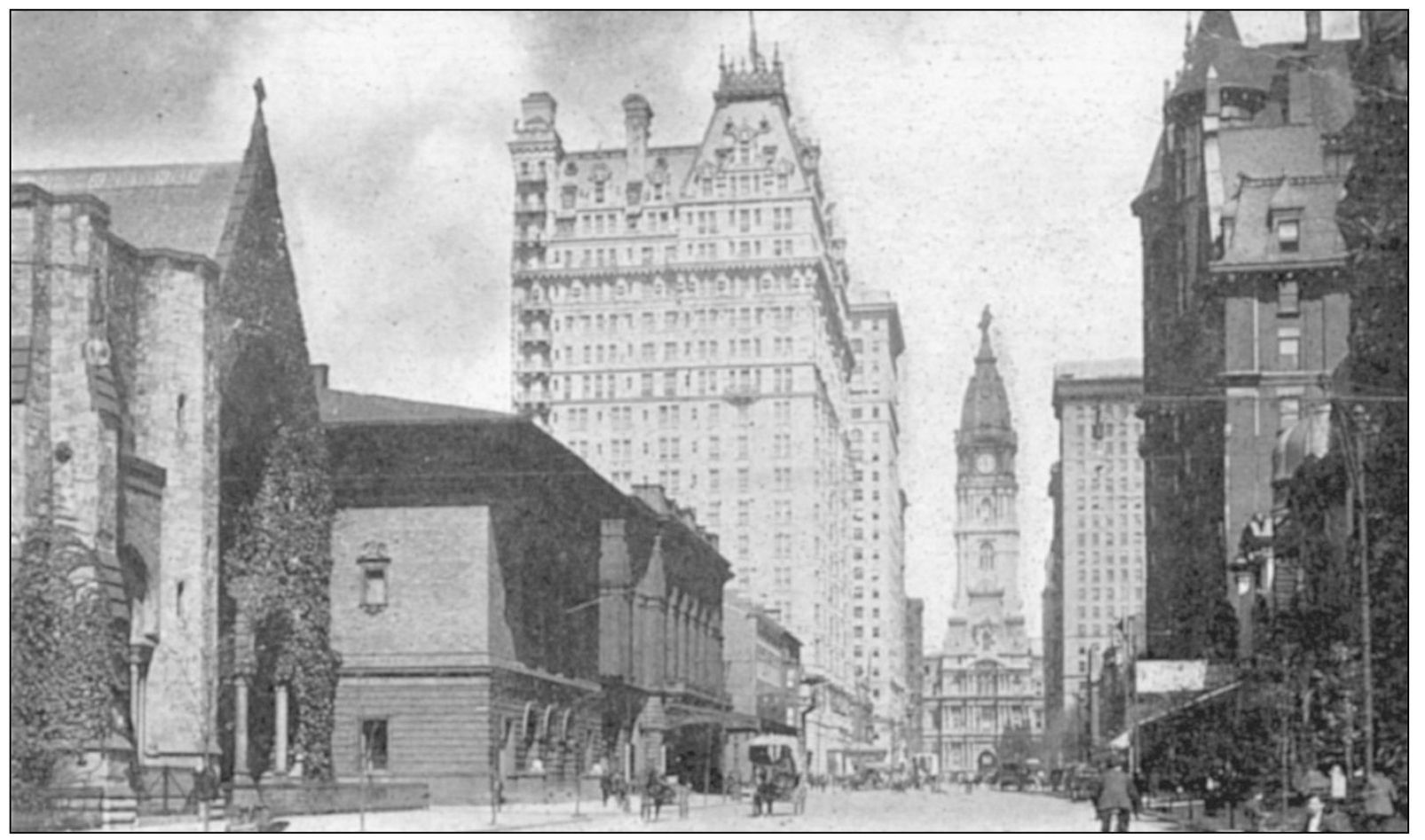

From the tower of Independence Hall looking to the west along Chestnut Street, the city unfolded. The closest buildings were the oldest, many dating from the colonial period. Beyond them were newer commercial buildings and a few modern skyscrapers. City Hall (background, far right) was the tallest building in the city at the time of this photograph. This remained true for many years to come.

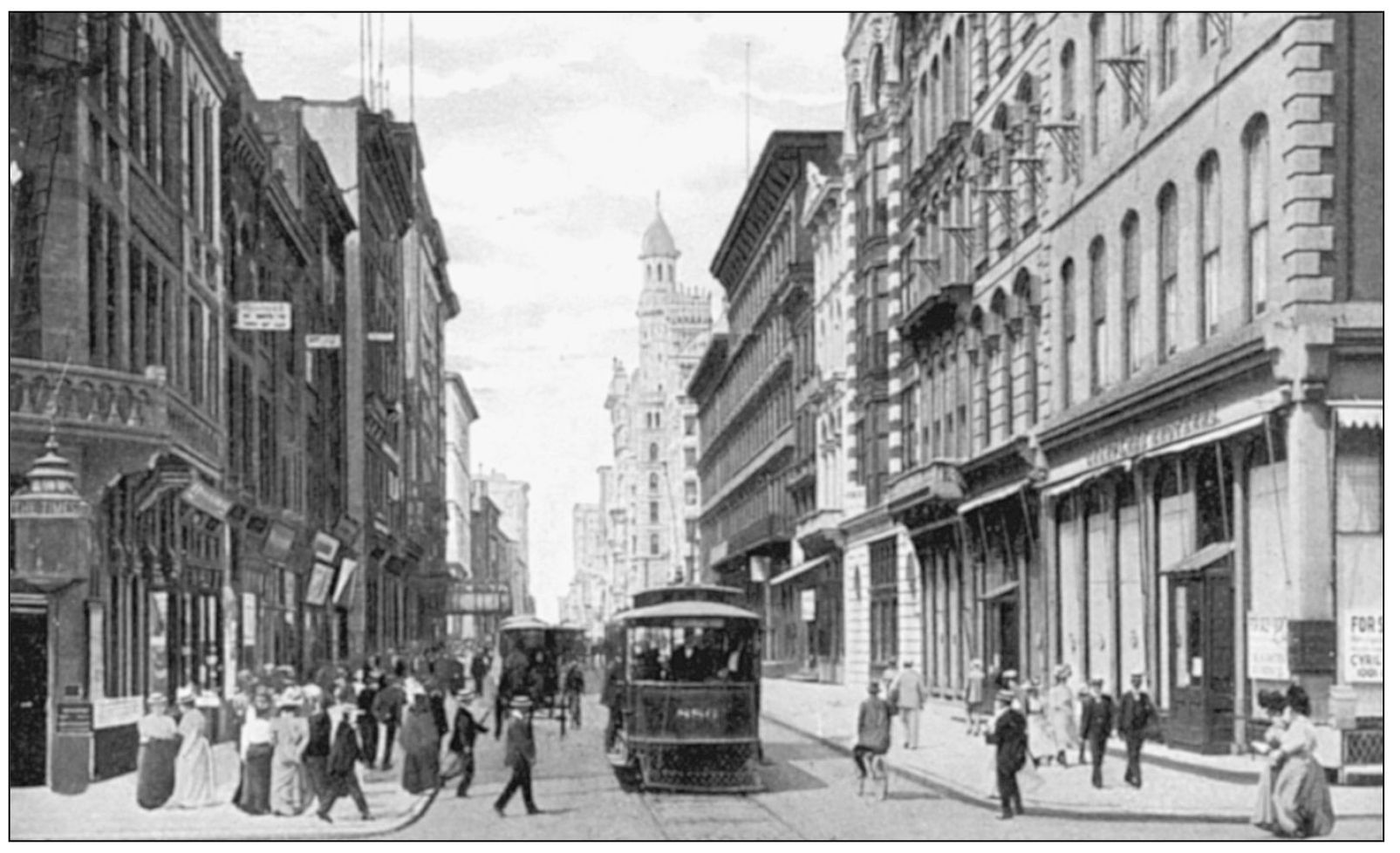

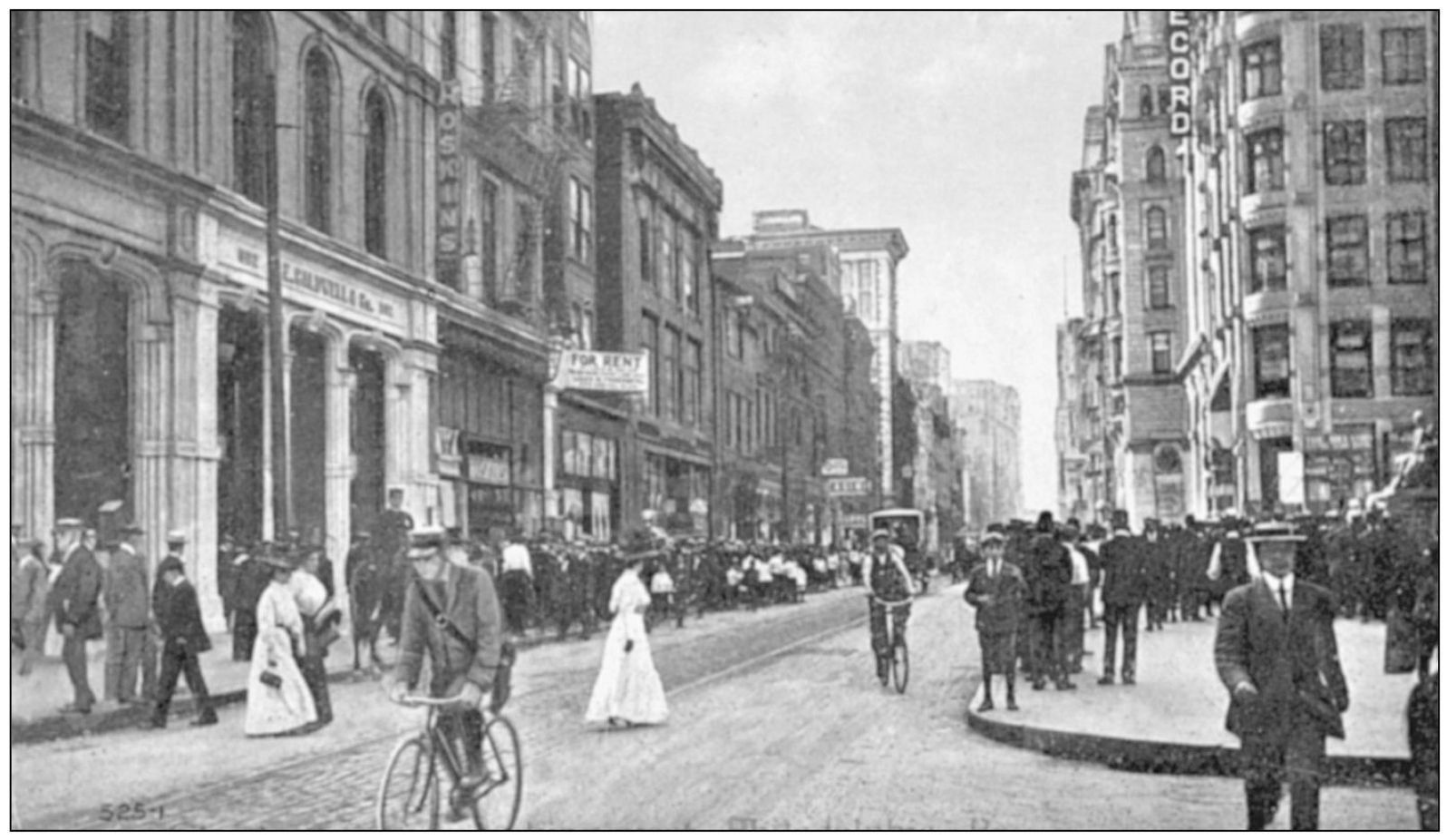

Down at street level, pedestrians had a similar view of the city. Known as juggernauts of death, the first electric streetcars had been introduced in 1892. As the automobile increased in popularity, horse-drawn vehicles, automobiles, and electric trolley cars competed for space on the citys narrow streets, resulting in massive traffic congestion. It was frequently quicker to walk to nearby destinations.

Philadelphia was famous for the layout of its streets, the plan for which was designed by William Penn. While the original city covered just two square miles, by 1925 there were more than 1,718 miles of streets. In 1684, Penn ordered the cross streets to be named numerically, while the east-west streets were to be named after local trees: Cedar, Pine, Spruce, Chestnut, Mulberry, Sassafras, and Vine.

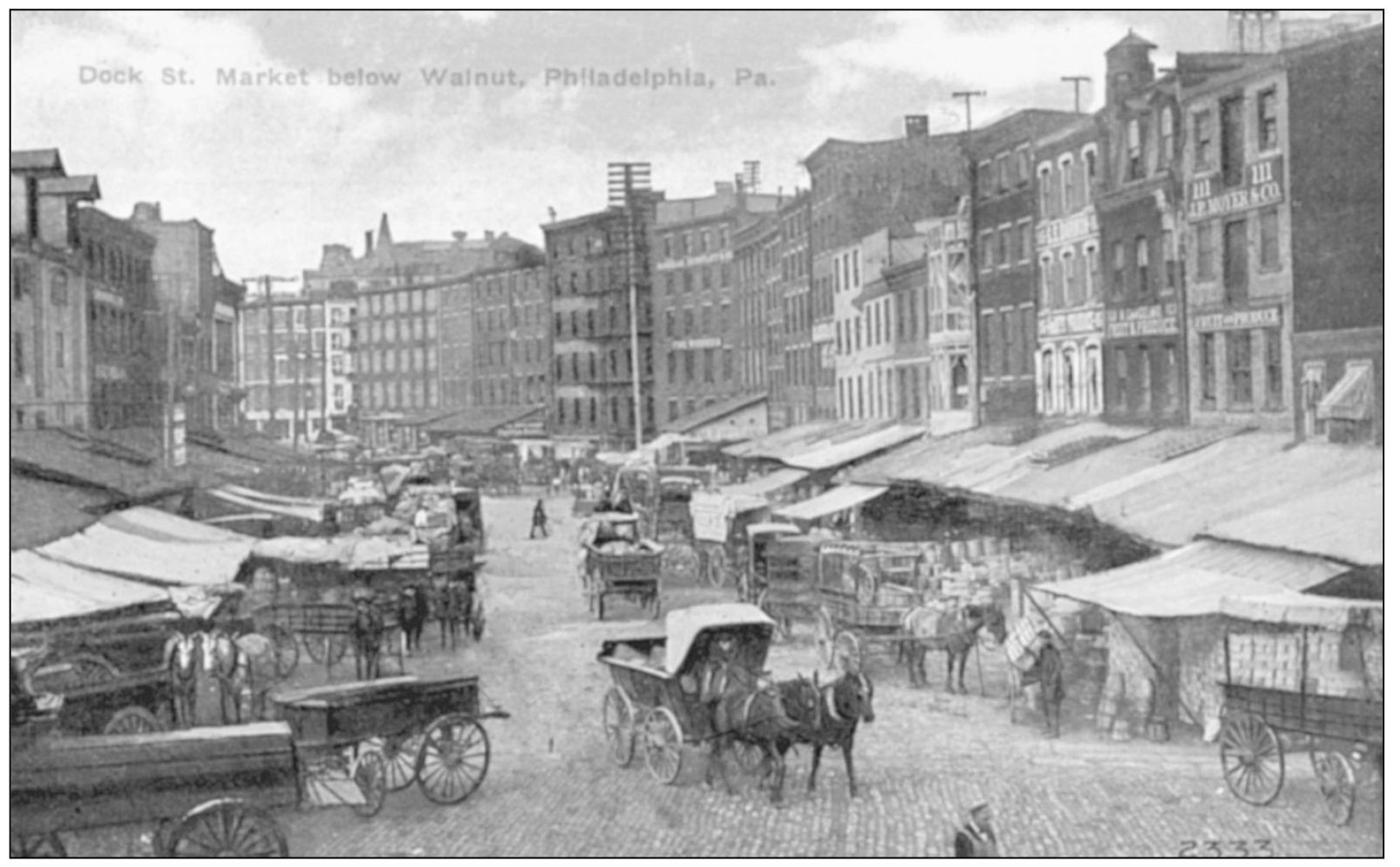

Running east and west from the Delaware River to Sixty-ninth Street, Market Street was the dividing line between the north and south sides of the city. It was also the center of the retail district in center-city Philadelphia. Many of the large department stores for which the city was famous, including John Wanamaker, Gimbel Brothers, Strawbridge & Clothier, Lit Brothers, and Snellenburgs, were located along Market.

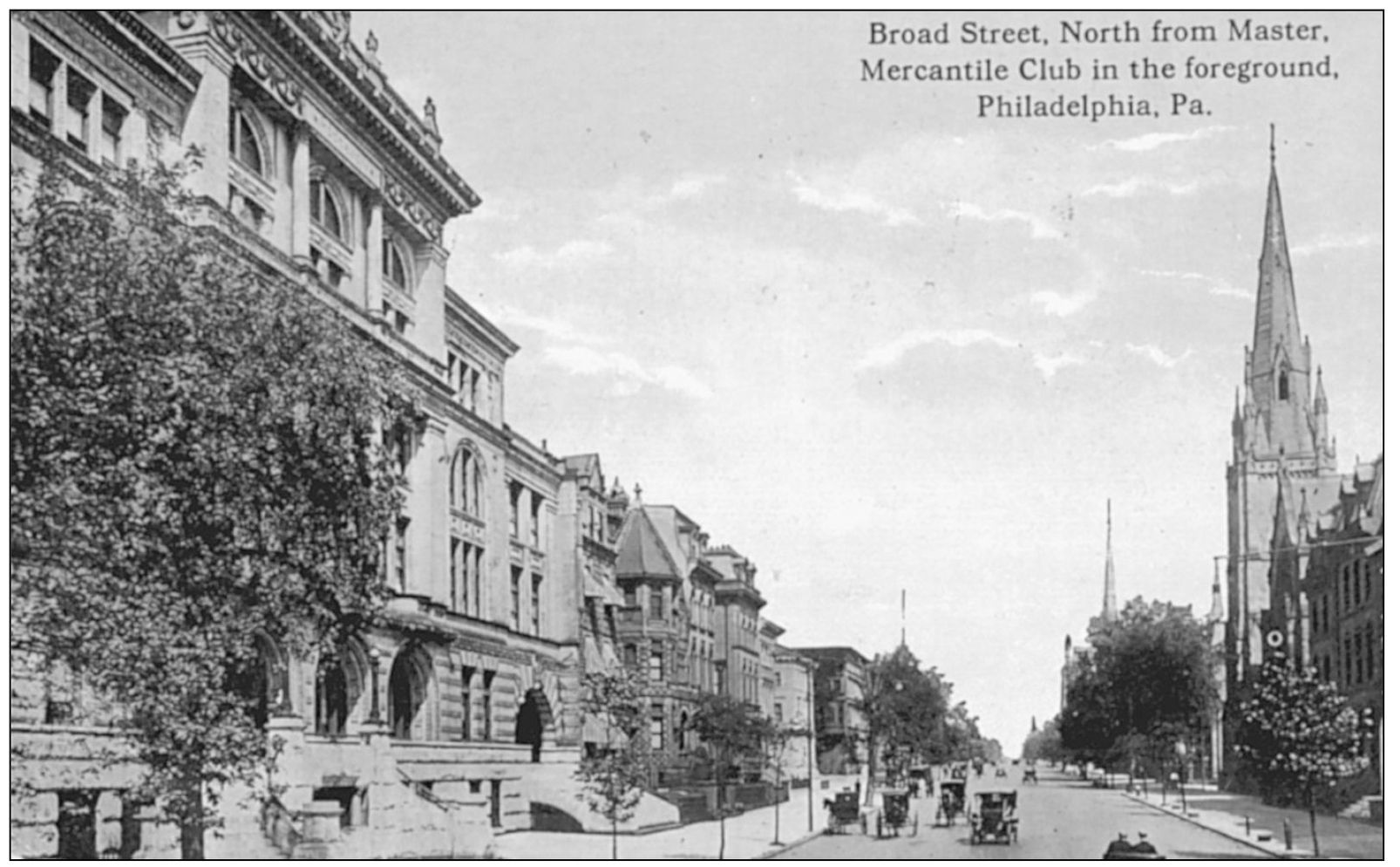

William Penns original design for Philadelphia called for a gridiron pattern of wide streets that intersected large public squares. While most of the streets had a width of only 50 feet, his plan called for High (now known as Market) and Broad Streets to be 100 feet wide, exceeding the widest streets in 17th century London. Broad Street, 12 miles long, was claimed, albeit erroneously, to be the worlds longest street.

While this view of North Broad Street and the massive Mercantile Club still presented an elegant appearance, the portion of Broad Street just north of Market had come to be known as automobile row. In 1914, the Packard Motor Car Company shared the street with Studebaker Automobiles, the Carter Car Company, and the Buick, Hupmobile, and Chalmers dealerships.