ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

A book such as Wings Over Florida , which celebrates Floridas rich and unique aviation history, could not have been written without the assistance of many people. We are grateful to Arcadia Publishing and our editor, Christine Riley, for having the foresight to believe that Wings Over Florida deserves a place in their publishing catalogue.

Florida has many wonderful museums possessing excellent photographic collections. Those museums whose collections proved especially valuable include: the Florida State Archives, the International Sport Aviation Museum, the St. Petersburg Museum of History, and the Tampa Bay History Center. Few libraries can claim a better collection of photographs than the Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library Systems Burgert Brothers Collection, and we are thankful for the opportunity to use them. Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University and Paul Camp, archivist of the University of South Floridas Special Collections, have been immensely helpful.

Florida has always been more hospitable to African-American aviators than most southern states. The many original airmen residing in Florida, including Nasby Wynn, Henry Bohler, and especially, Hiram Mann, have been so instrumental in our understanding of the contributions made by the Tuskegee Airmen. Ruth Clifford Hubert, Dorothy Ebersbach, and Marion Tibbets graciously shared favorite photographs and stories about women in aviation, most notably the Women Airforce Service Pilot (WASP) program in which they participated during World War II. William Kidney, a Civil Air Patrol historian, has been instrumental in helping us understand the contributions of the CAP fliers during the war. Thanks also to the United States Air Force and Navy for the use of their photographs.

The people at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration were superb in their assistance. We are indebted to Ken Thornsley and Margaret Persinger of the Kennedy Space Center, and Debbie Dodds of the Johnson Space Center for their assistance. Thanks also to the Tampa Times , the Lakeland Ledger , Peter J. Sones Jr., M.D., the crew of the MetLife airship, Seminole-Lake Gliderport, and Brenda Geoghagan of the Hillsborough County Aviation Authority. As always, we marvel at the work that Kelly, Bruce, and the staff of Zebra Color Photo Lab perform with old photographs. Their skill helps to make our books what they are.

Edward C. Hoffman Sr., president of the Florida Aviation Historical Society, should be considered as the dean of Floridas aviation history. His input and support are always priceless.

Find more books like this at

www.imagesofamerica.com

Search for your hometown history, your old stomping grounds, and even your favorite sports team.

One

FLORIDAS FIRST FLIERS

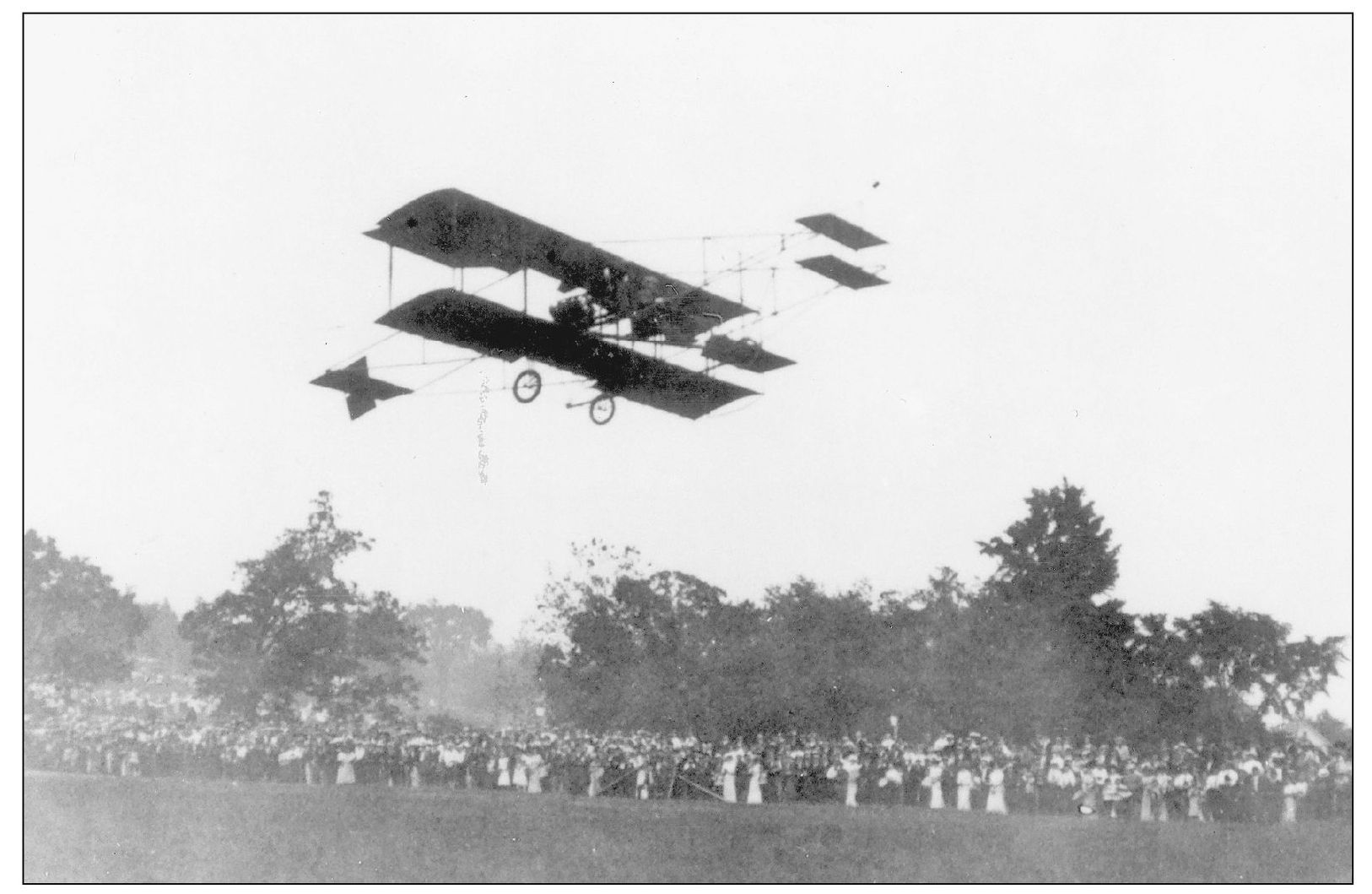

Charles K. Hamilton was one of the first men to fly in Florida. Since the sandy shores of the Atlantic Ocean made an excellent, unobscured runway, Hamilton used Ormand Beach for his experiments with gliders as early as 1906. As pictured, the legendary pilot performed frequent flying exhibitions at Jacksonville. Hamilton, a one-time dirigible pilot, circus parachute jumper, and trick bicyclist, was small in stature, had blazing red hair, and big ears. A consummate showman, he had a propensity for alcohol and was seldom seen without a cigarette hanging from his lips. Trained by Glenn Curtiss, Hamilton was the 12th pilot to be licensed to fly in America. Despite reportedly having broken every bone in his body in aviation accidents, Hamilton died not from injuries, but from pneumonia on January 22, 1914. (Private Collection.)

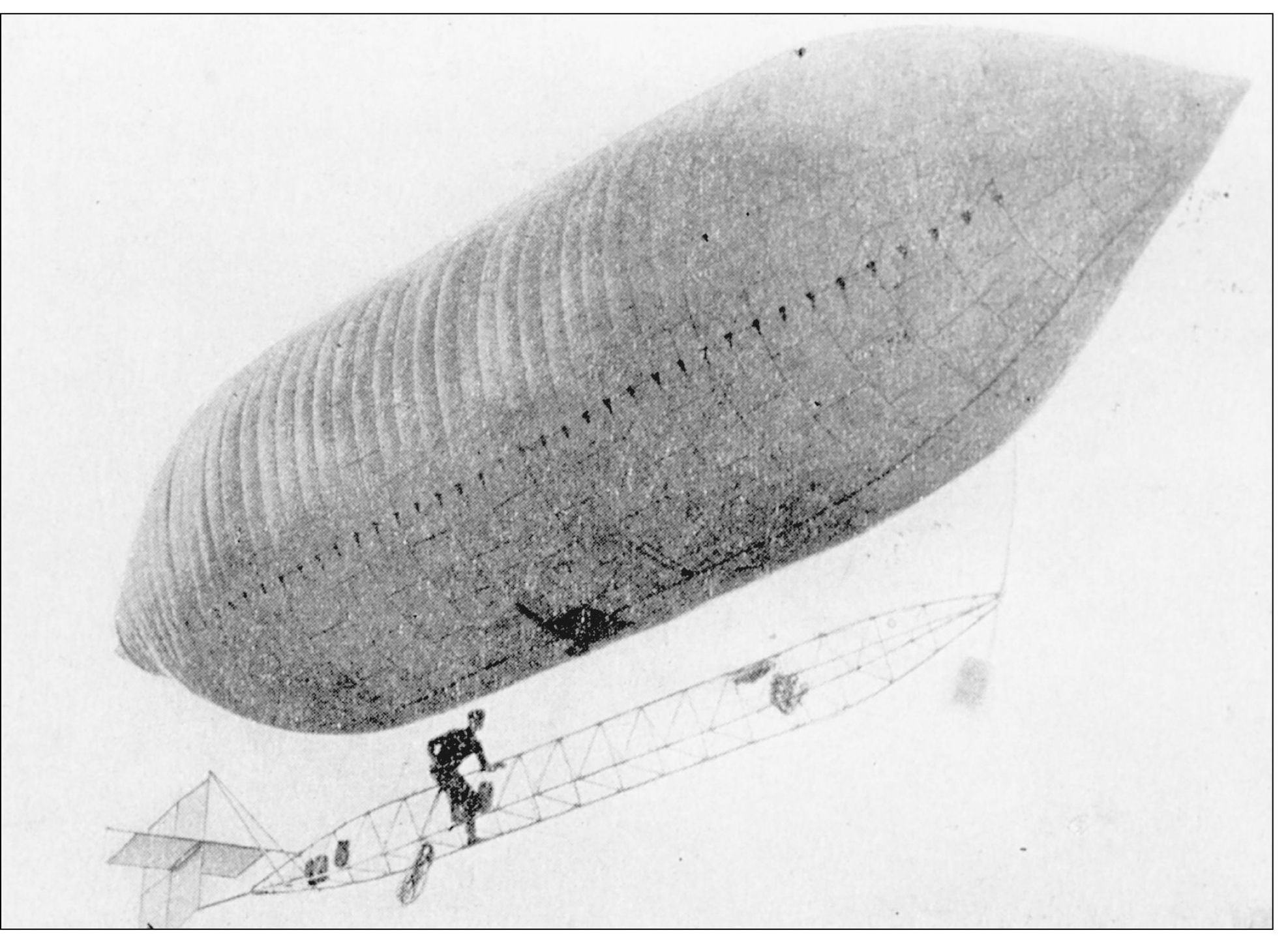

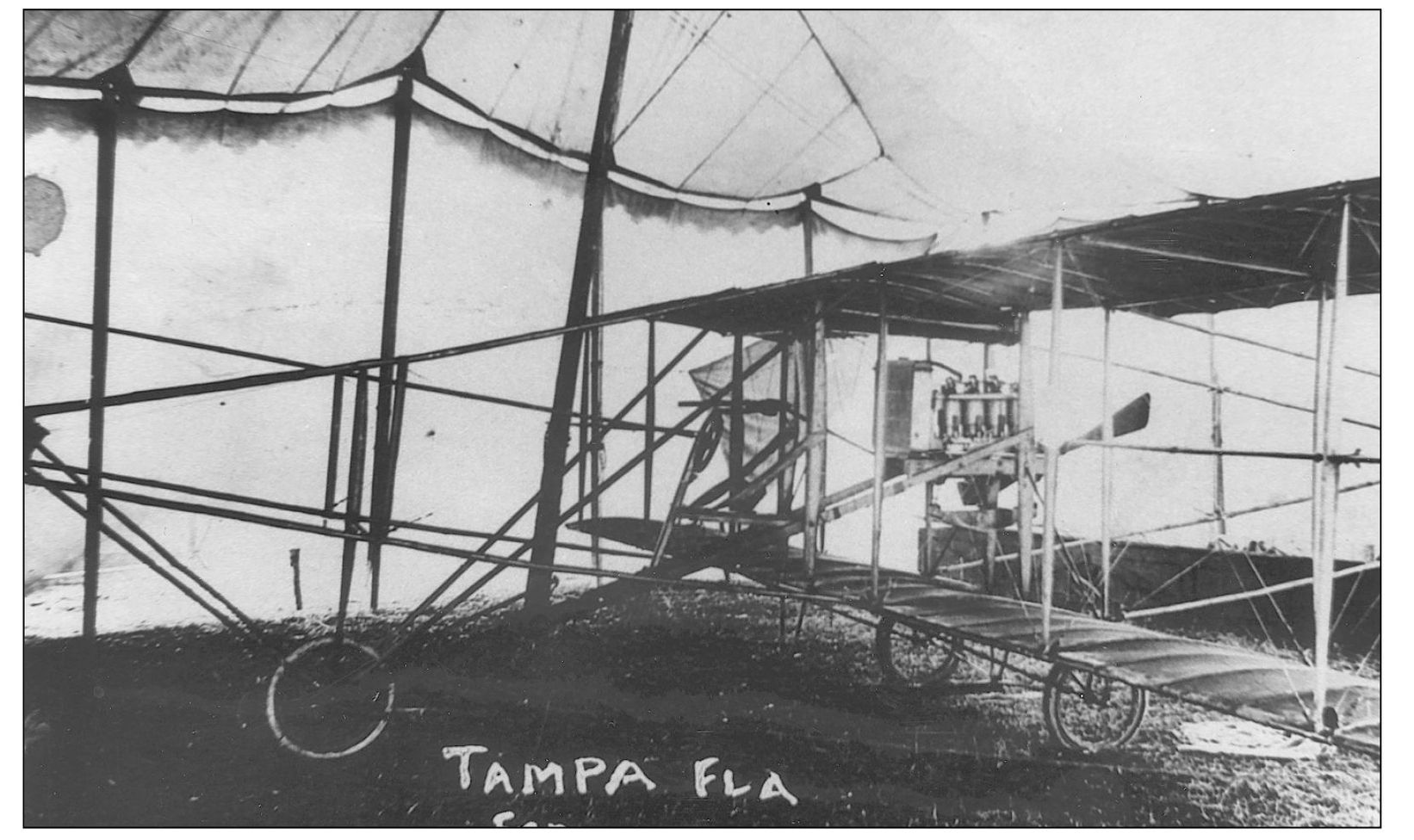

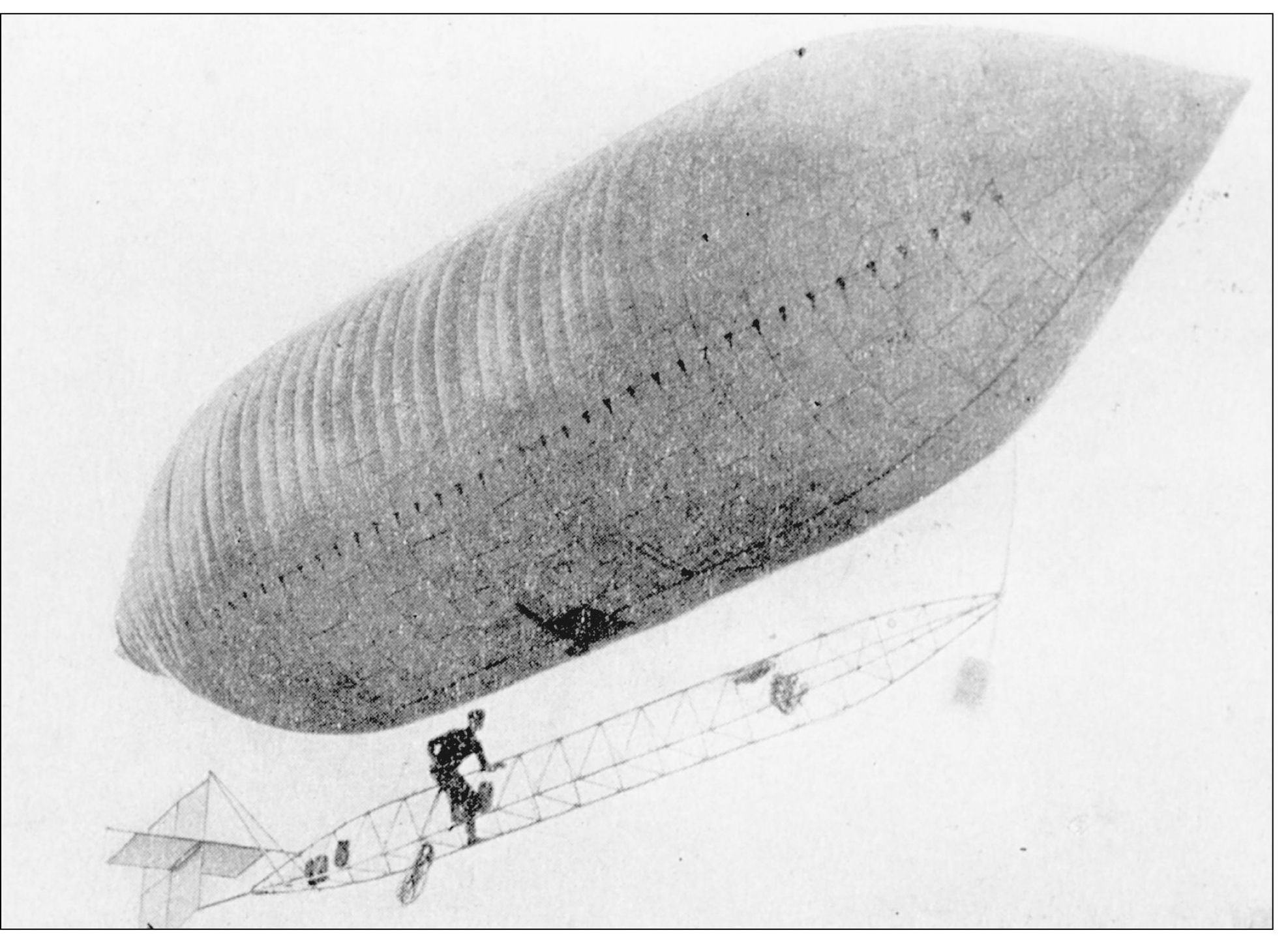

Aviation came to Tampa in the form of a lighter-than-air airship in February 1910. As the city celebrated the Great Panama Canal Exposition, thousands of people turned out to see dirigibles, balloons, and a promised flight of a Curtiss biplane. On the afternoon of February 14, E.J. Parker piloted the Stroebel dirigible past the Tampa Fairgrounds grandstands at an altitude of only 20 feet above the field. Then, despite a heavy breeze, Parker ascended and flew over Tampa. As Frank Goodale piloted a second dirigible past the grandstand, he steered toward the minarets of the Tampa Bay Hotel and then crossed the Hillsborough River toward Ybor City. The remaining pilot, Stanley Vaughn, tilted the nose of his dirigible upward and in minutes attained an altitude of several hundred feet. With three airships in the air, the flight was described as spectacular in character. The highlight of the event, however, was the nighttime dirigible flight guided by a powerful searchlight. Promising to bring another flying extravaganza to Tampa the following year, Charles J. Stroebel stated, Climatic conditions in South Florida during the winter months are as near perfect for airship flights as could be desired. (Private Collection.)

The best-known early exhibition flyer, Lincoln Beachey brought his Curtiss Flyer to Tampa in February 1910 as part of the Great Panama Canal Exposition event. On December 27, 1908, over Jacksonville, he piloted the first motor-propelled airship to fly in Florida. In February 1910, the first heavier-than-air flight in Florida took place in Orlando when he won a $1,500 prize for keeping his Curtiss-built, pusher biplane in the air for five minutes. Returning to Tampa in March 1911, Beachey made the first publicly viewed night flight in an airplane. (Burgert Brothers Collection, Tampa-Hillsborough County Public Library System.)

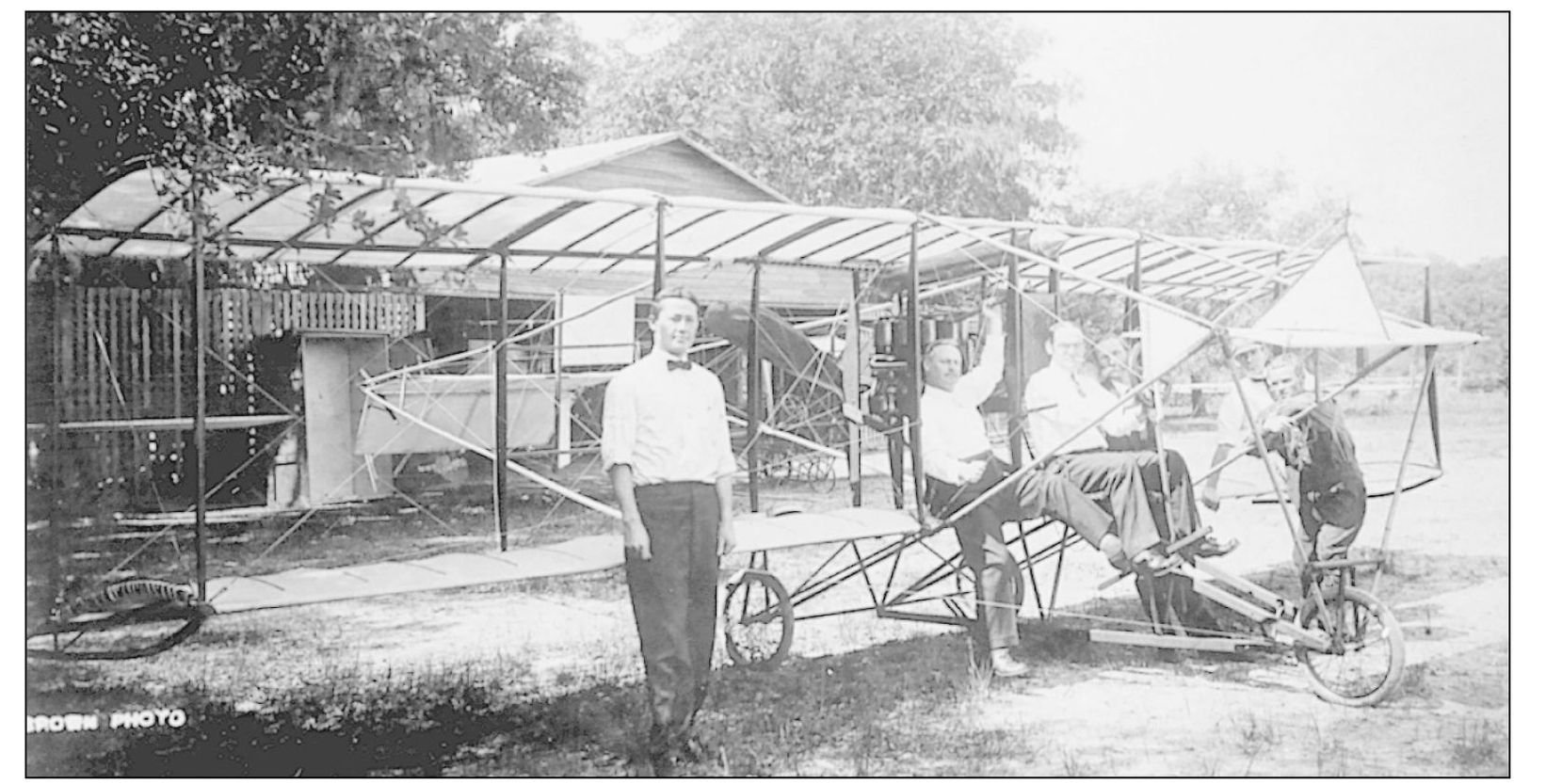

This home-built biplane, displayed outside a private hangar at Kissimmee in 1910, was not much more advanced than the one used by the Wright brothers in 1903. On July 17, 1908, the Kissimmee Valley Gazette reported a proposed municipal ordinance intended to regulate the height over the city within control of the law and set the amount of licenses to be paid by owners of aircraft. Although never adopted, that ordinance gave Florida the dubious distinction of being the birthplace of aviation legislation. (Florida State Archives.)

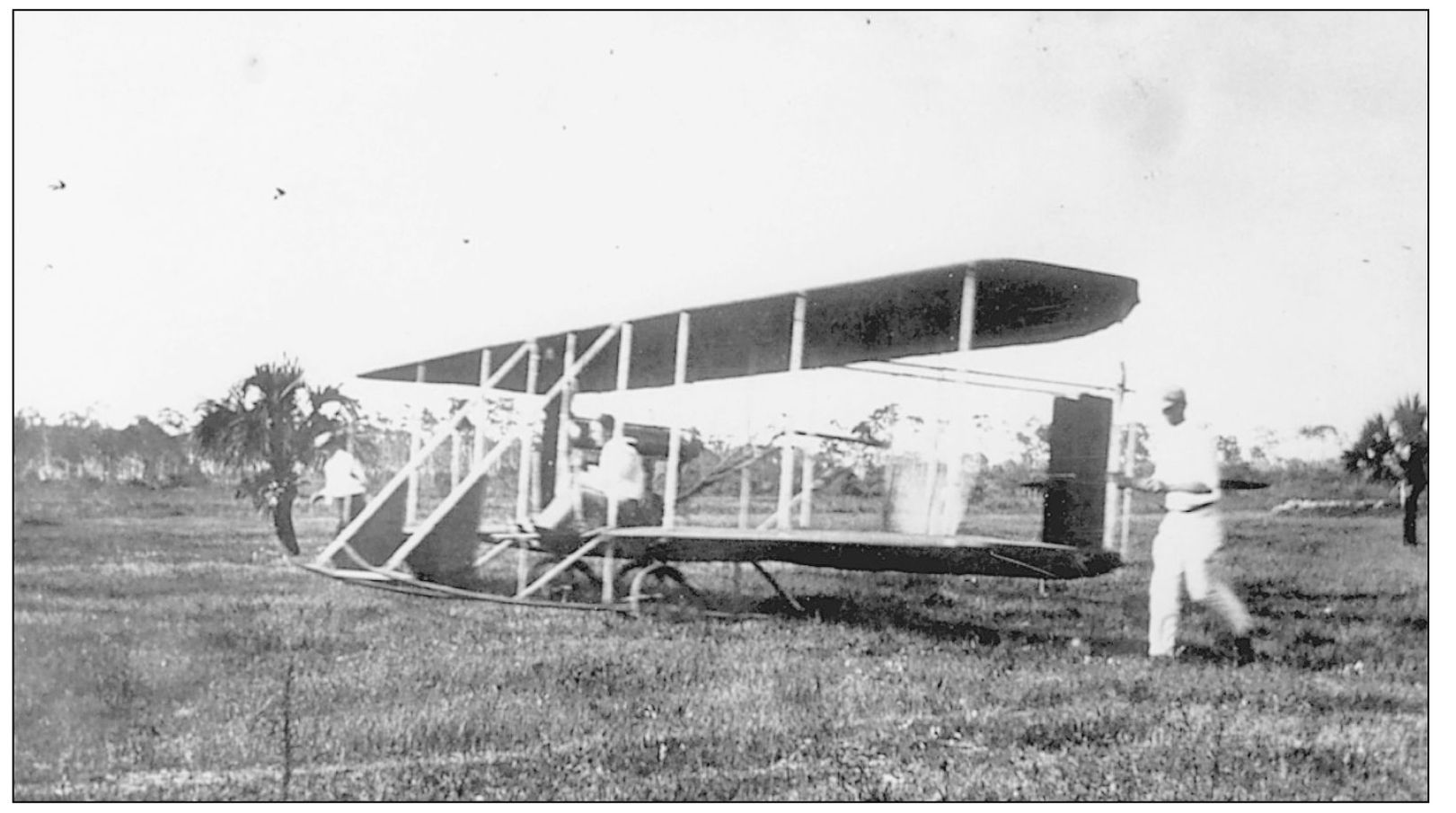

Fair managers and promoters frequently hired aviators to insure large crowds at their events. Howard Gill, of Baltimore, Maryland, was trained by the Wright brothers and became part of the Wright exhibition team that toured the United States. When Gill was retained to fly his skeleton-framed pusher biplane in celebration of Miamis 15th anniversary in 1911, he received $7,500 for making the first airplane flight over the city. (Florida State Archives.)