First published in 2014 by S.I. Publicaties BV

Postbus 188, 6860 AD Oosterbeek, Netherlands

Reprinted in this format in 2016 by Pen and Sword Military,

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

Copyright Guus de Vries, 2016

ISBN 978 1 47385 668 4

The right of Guus de Vries to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor by way of trade or otherwise shall it be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Typeset by Pen & Sword Books Ltd

Printed and bound by Replika Press Pvt. Ltd.

Translated into English by Britta Nurmann.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military, Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social History,Transport,True Crime, and Claymore Press, Frontline Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

Pen and Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail:

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

Introduction

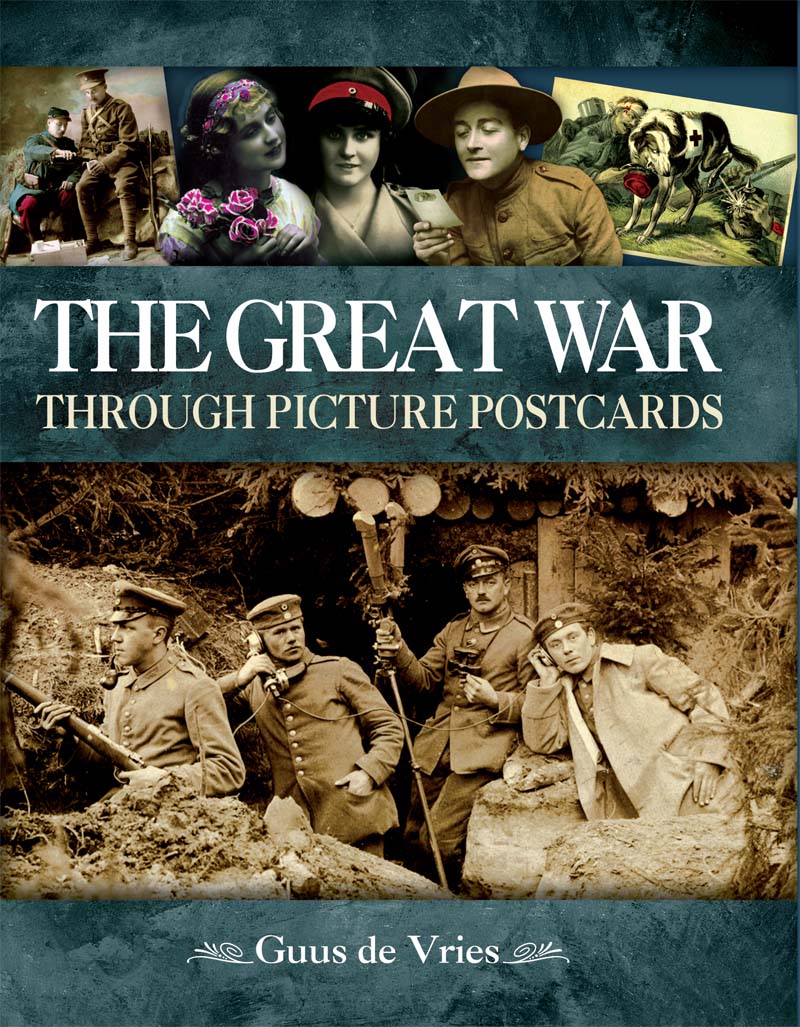

P ICTURE POSTCARDS from the First World War offer a multi-layered source of information, which researchers have only mined to a small degree up to now. The postcards sent by and to soldiers not only mirror the events in the different theatres, but also give a unique view of the daily life both on the front line and at home, in all warring countries. They transport the dreams, wishes and desires of the men on the battlefields and paint a picture of the changing role of women in everyday life. In this way, not only do they offer a complex picture of reality, but also allow deep insights into the minds of the artists, publishers and producers, as well as the people who sent the cards in the first place.

Collecting picture postcards had been a popular pastime since their introduction in 1869 and so many of the cards had survived in albums and boxes along with military mail. The German Reich recognised the positive effects of home contacts on morale, therefore the letters and postcards delivered by the field postal service were subsidised as soldiers mail, handled by special field post offices called Feldpostexpedition and carried between the front and home by the millions. The designs were diverse, ranging from lithographed and sometimes even embossed works of renowned artists, to pictures taken by the writer as a personal greeting from the field, and sent back to loved ones at home.

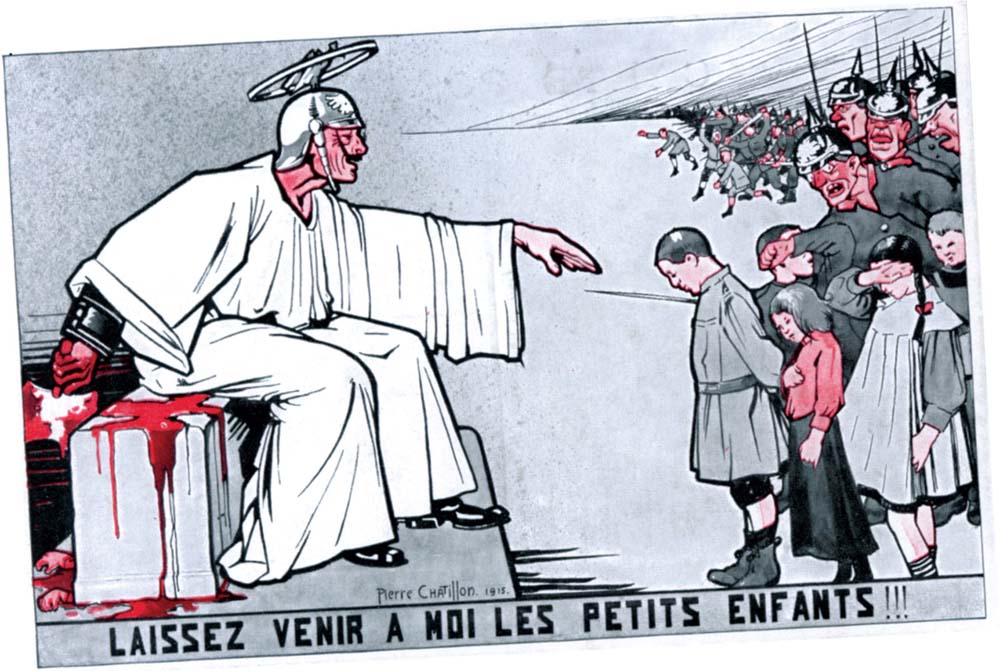

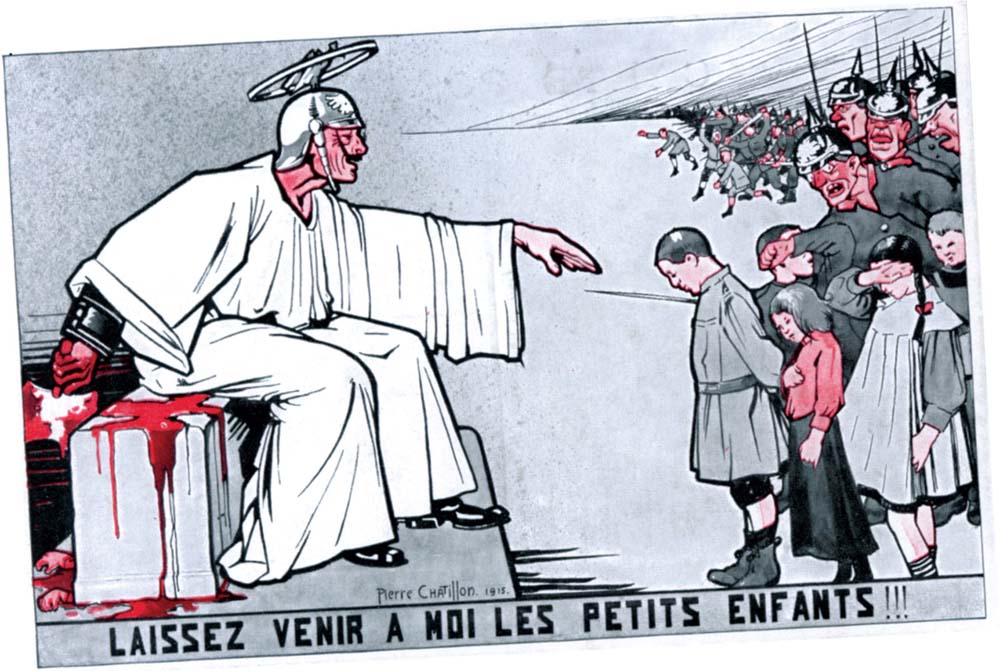

Let the little children come unto me!!!

Picture postcard from 1915 with an illustration by the Swiss graphic artist Pierre Chtillon (1885-1974). He depicted Emperor Wilhelm II as God, chopping off childrens hands. During the war, stories such as this of atrocities allegedly committed by German soldiers were repeated again and again. Even though these rumours would later turn out to be completely unfounded, they still were a popular motif for postcards in order to emphasise the huge guilt of the German troops.

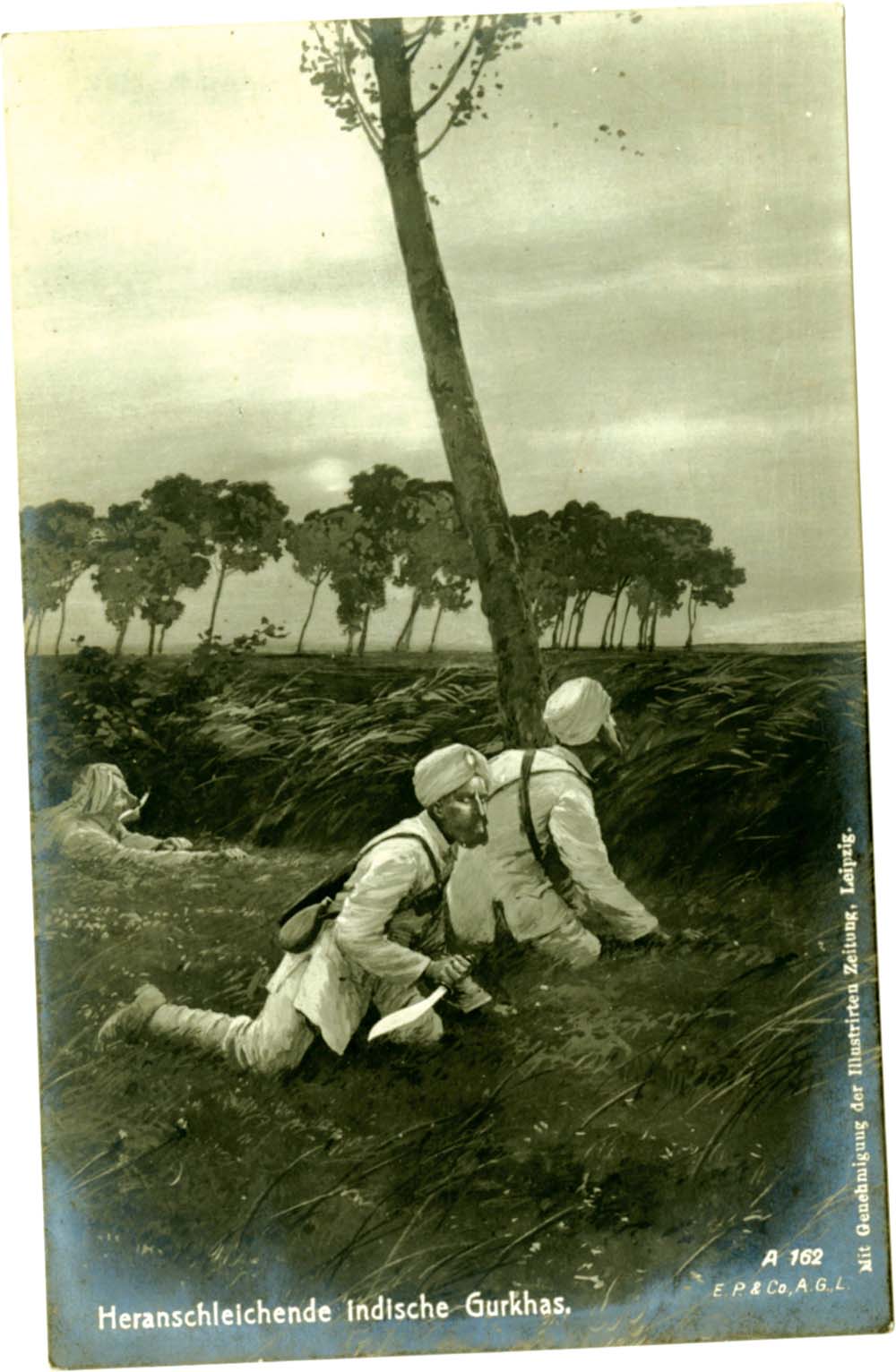

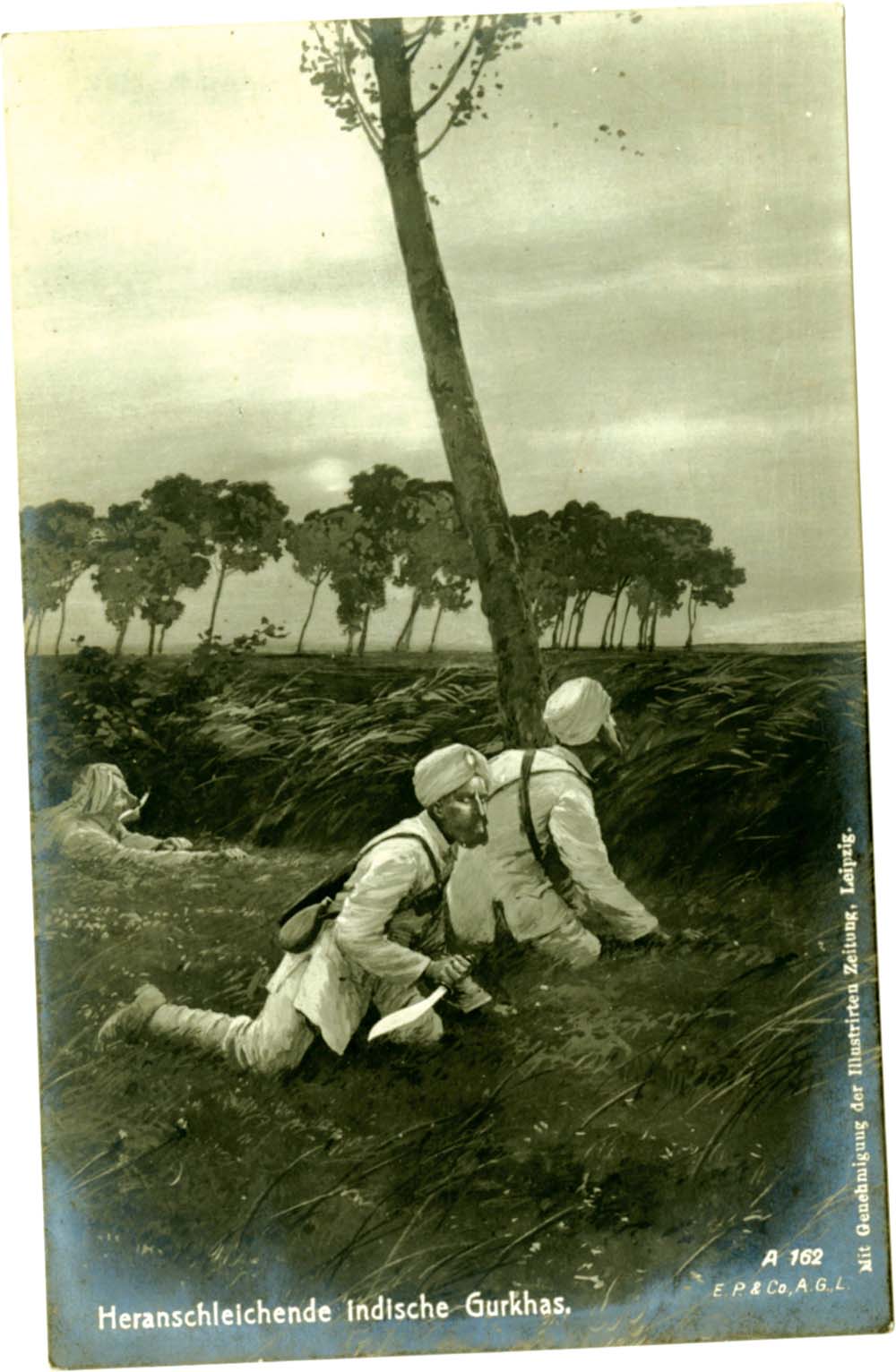

Indian Gurkhas sneaking up.

Among the troops of the British Commonwealth were several battalions of Gurkhas. These professional soldiers from Nepal were feared among their enemies, not least because of their skills in wielding the heavy, curved, all-purpose knife called the Kukri. Motifs portraying the enemy as respectable and even dangerous, such as on this German picture postcard, are relatively rare.

The aim of this publication is to document how the First World War was portrayed by and through picture postcards from three different vantage points:

How were the real events pictured?

How were emotions and perceptions of the war communicated?

Which artistic and stylistic devices were used to influence and manipulate public opinion?

This research is based exclusively on the various motifs of the picture postcards, not the private messages of the senders, which were astonishingly consistent across all countries and often only served to communicate that personal health was still maintained and to express gratitude for received mail and comforts. Critical reports are rare and perhaps more likely to be found in letters, which are not as easily censored as postcards.

The postcards are grouped into twelve chapters in which accompanying texts provide the reader with an overview of the warring states and their armies, the developments at the front and at home, and the weapons in use. The scope of this book allows only glimpses at the four years of the war to end all wars, and military historians will hopefully forgive the author and the publisher for occasional generalisations.

All postcards shown in this book are from the collections of S.I. Publications and VS-BOOKS.

Guus de Vries, September 2014

Chapter 1

War and Picture Postcards

Mail and Morale

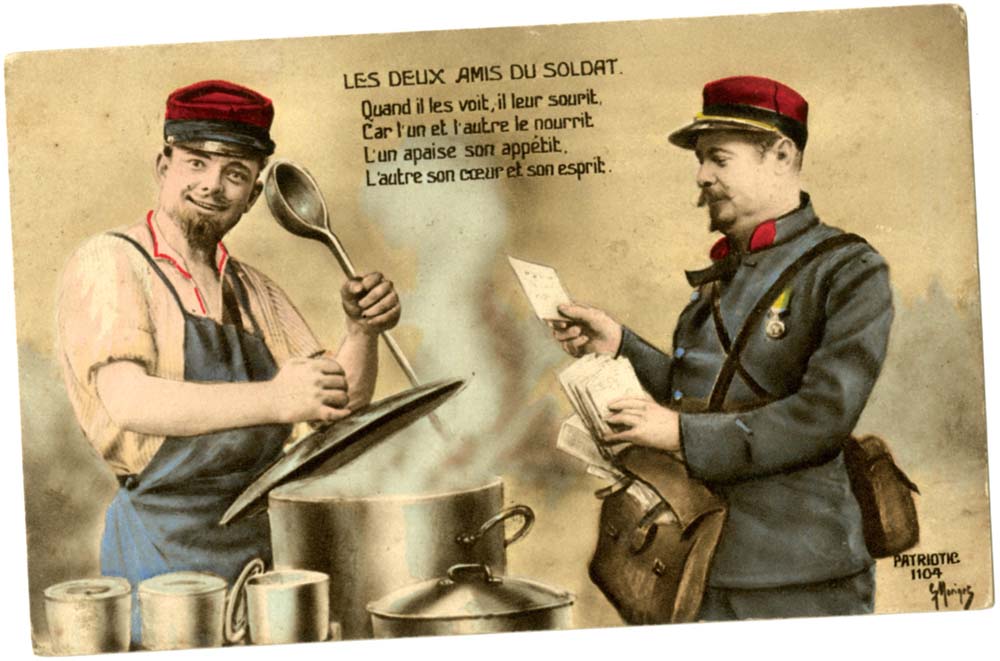

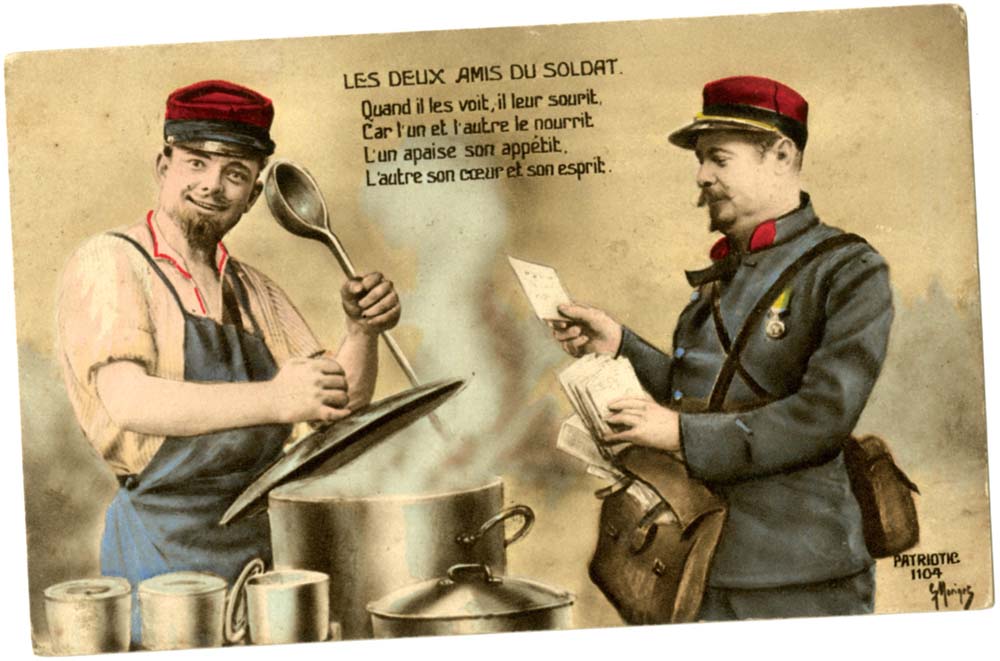

D uring the First World War, the most important people in a soldiers life were the cook and the postman. The distribution of mail and comforts from home were the emotional highlight of the day, and contacts with the outside world were an important support, helping the soldiers to bear many deprivations. Knowing that there was a normal life outside the theatre of war, receiving mail meant a connection to home and was extremely important to the soldiers. It meant that their minds could, temporarily at least, flee the hell they were captured in. On the other hand, receiving military mail from the front was at least a sign of life, and so the daily visit of the postman was eagerly anticipated by those at home.

The military authorities were aware of the massive influence mail had on the morale of the troops. Consequently, sending mail was often very cheap or even free of charge for active soldiers, even though it required extensive and costly organisation. In 1918 for example, the German Armys field post offices were staffed by about 8,000 mail clerks and 5,000 supporting troops, while in 1917, the British Field Post Office employed about 4,000 personnel. Of course, the number of picture postcards, letters and parcels transported by the various field post services is beyond imagination.

Next page

Contents

Contents