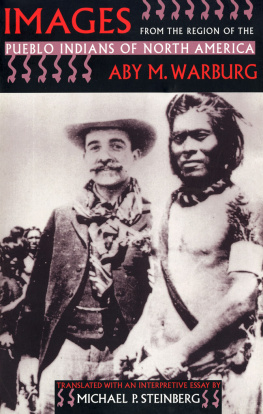

Aby Warburgs Kreuzlingen Lecture: A Reading

Il Fanciullo del West

The story is by now famous. In September 1895, the young art historian Aby Warburg left Florence for New York to attend the wedding of his brother Paul. He had much work planned during his projected three-year stay in Italy, which had begun the previous year, and there is no apparent evidence that he intended his American trip to be a long one. Curiously, his distaste for New York and the society to which he was introduced there served to prolong his American journey and make it into an episode of profound importance to his work and life.

In 1897, Warburg recalled his impression of New York in terms of the practical foundation of this overrichly assorted, largest department store in the world. Paul Warburgs marriage to Nina Loeb reinforced the alliance of two prominent investment banks: M. M. Warburg of Hamburg and Kuhn-Loeb of New The westward escape from New York thus recapitulated Warburgs life path and its two inner exiles: away from banking and away from established modes of art historical scholarship.

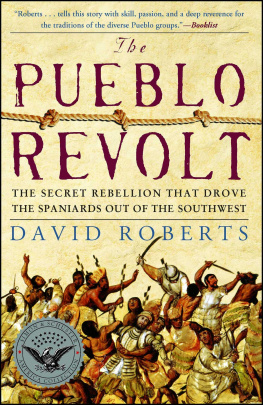

Warburgs American destination became the pueblos of the Native American Southwest. As E. H. Gombrich observed in his biography, Warburgs distaste for gilded American modernity fit into a larger, developing discomfort with the formalist modes of art history in which he had been trained. At this early point in his career, he seems to have begun to formulate ideas of the conjunctions between the production of culture itself and of aesthetic and symbolic images in particular. Thus the desire to reintegrate the viewing of art into the interpretation of culture led to the retrieval of the phenomenon of cultural production in primitive society. In his notes of 1923, and in a somewhat condescending remark on the attitudes of his own youth, Warburg added that the will to the Romantic had contributed to his westward fever.

Gombrich suggests further that Warburg may have been influenced by the Berlin ethnologist Adolf Bastian, who had recently warned that native cultures all over the world were in decline and if the material for a study of primitive man was not collected now, it would be irretrievably lost. possible exception of La pense sauvage) and the evolutionism that looks to primitive cultures for a shared proximity to a pure and prehistorical cultural ground zero (Frazer, Freud, and Eliade). In the 1890s, Warburg was operating within this evolutionary framework. Another distinction, equally important, presents itself as well: that between liberal and romantic evolutionism. To Frazer and Freud, evolutionism meant the transcendence of primitivism qua cultural barbarism. To Jung and Eliade, evolutionism meant the loss of something precious and authentic. Warburgs early evolutionism implies the firstthe liberalagenda, but the evolutionism itself does not last. Images from the Region of the Pueblo Indians offers his new perspective, which took a lifetime to generate.

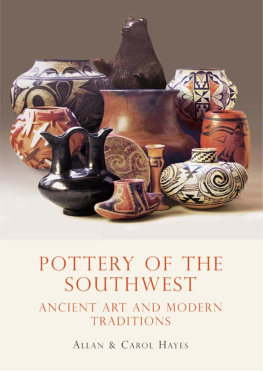

Warburgs American itinerary took form through a series of personal meetings and connections. His brothers new wife was the sister of James Loeb (later the founder of the Loeb Classical Library), who invited Warburg to visit Harvard. An initial interest in Dakota Indian wall paintings took him to Harvards Peabody Museum and onward to Washington and the Smithsonian. Cyrus Adler, the Smithsonians librarian, professor of Semitic languages at Johns Hopkins, and an acquaintance of the Loeb and Schiff families, introduced him to Jesse Walter Fewkes and F. W. Hodge, and James Mooney, who in turn introduced him to Frank Hamilton Cushing. In New York he also met Franz Boas, whose own German-Jewish origin provided an additional point of contact. Adler showed Warburg ceramics that Fewkes had removed from Hopi; Cushing spoke with him about the symbolic ornamentation on the pottery; and Mooney first told him about the Hopi snake dance.

The contact with Mooney proved the most enduring, and it might be fair to speculate as to the intellectual reason for this. In 189293, Mooney had published, in the Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology, his

Claudia Naber has recently reconstructed Warburgs American itinerary with great specificity.

Warburg left Washington at the beginning of November and traveled via Chicago and Denver. He says in his notes of 1923 that the firm of Kuhn-Loeb had procured for him, during his stay in Washington, letters of introduction from the ministers of war and of the interior. In Chicago, he presented a letter of introduction signed by a certain Mr. Seligmann to the railroad magnate Robinson and received a pass for free travel on the Mexican Central Railway, as well as a recommendation to the governor of New Mexico and to other prominent people in the region of the Pueblo Indians and a request

Warburg was guided through the Mesa Verde cliff dwellingsthe American Pompeii, as he described them in a letter to his mother and sister written from Santa Fe on 14 December 1895by John Wetherill, Richards brother. (Richard was in New Mexico at the time, trading for Indian objects.) From Mesa Verde, Warburg traveled into New Mexico and visited the pueblos of San Juan, Laguna, Acoma, Cochiti, and San Ildefonso. He observed the antelope dance while at San Ildefonso. February and March of 1896 he spent in California, enjoying his leisurefor example, a stay at the Coronado Beach Hotel (opened in 1888)but also preparing for a springtime return to the pueblos. As well, he visited the newly founded campuses of Stanford University and the University of California at Berkeley.

At Stanford, Warburg had several discussions on Hegel and F. T. Vischer with Julius Goebel, a German-born professor of literature; and through Goebel he was introduced to Earl Barnes, a pioneer in the study of child psychology. Barnes had spent time in the early 1890s conducting experiments on childhood creativity with students in the California elementary schools. He would first read aloud, from the Struwwelpeter stories, the Johnny-Head-in-the-Air excerpt in which lttle Hans falls into a creek during a storm; then he would ask the children to illustrate the story. Warburg latched on to the specific image of the storm and later conducted the same experiment with Hopi schoolchildren.

At the end of March 1896, Warburg returned from California to the Southwest, arriving first in New Mexico Warburg left the region at the beginning of May and in fact never observed the snake dance around which he later constructed his writing about the Hopi.

The central episode of Warburgs visit to the Hopi was his administration of Earl Barness experiment on a group of fourteen Hopi children at the Indian Service School at Keams Canyon on 24 April 1896. Following Barness model, Warburg told the children the story of Johnny-Head-in-the-Air: It was a dark cloudy day with much lightning. A mother told her little boy not to go out, but he went out into the storm. The storm became so terrible that he turned back, fell over a dog that he did not see and stumbled into a pond where his father found him and got him out with a long pole. ). In Warburgs 1896 conceptualization, therefore, Hopi culture was on the road from primitivism to rationality and modernity.

As far as Warburgs conceptualizations of 1896 are concerned, the question of to what extent the idea of modernization through symbolic form either generated the dialogue with Hopi culture or was generated by it is very difficult to answer. In his notes to the lecture on the Hopi serpent ritual, which he prepared in the Kreuzlingen sanatorium for 21 April 1923, Warburg stated the importance to his subsequent work of his American journey. Although we cannot know where and how to draw the line, we have to allow for the separationdistancebetween his actions of 1896 and his recollections of 1923: I did not yet realize that, as a result of my American journey, the organic connection between the art and the religion of primitive peoples would become so clear to me, so that I could see so clearly the identity, or rather the indestructibility of primitive manwho remains the same in all times, so that I could draw him out as an organic entity precisely in the culture of early Renaissance Florence and, later, in the German Reformation. In a blunter statement of the same sentiment, Warburg wrote, in English, on 17 May 1907, to James Mooney of the Smithsonian: