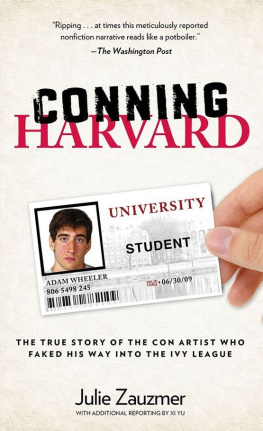

Dedicated to all those who uphold Harvards standards

Copyright 2012 by Julie Zauzmer

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed to Globe Pequot Press, Attn: Rights and Permissions Department, PO Box 480, Guilford, CT 06437.

Lyons Press is an imprint of Globe Pequot Press.

Some of the reporting and research for this book was funded by and conducted for The Harvard Crimson. Such materials are used here with permission.

Project editor: Meredith Dias

Layout: Mary Ballachino

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Zauzmer, Julie.

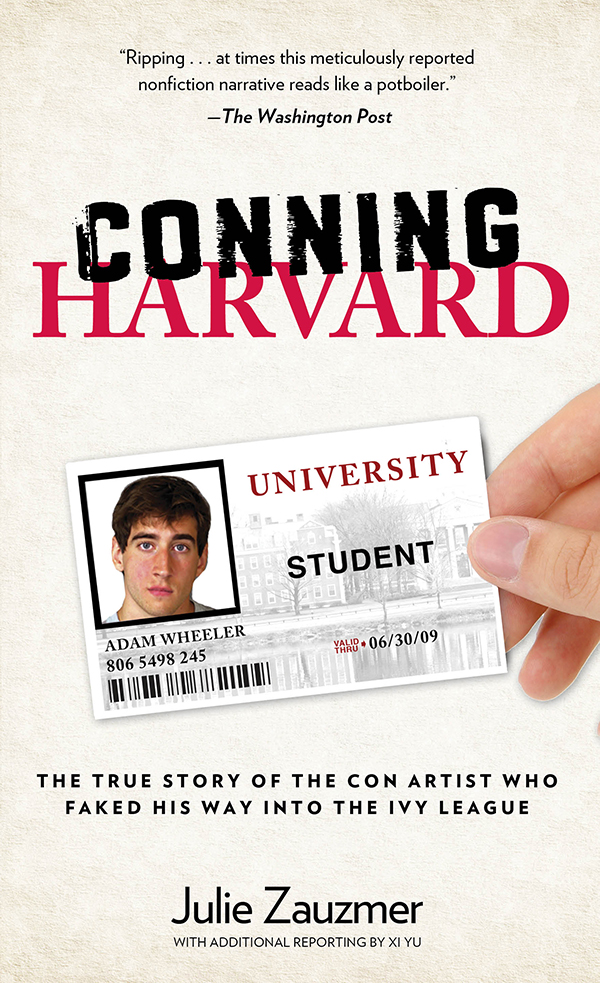

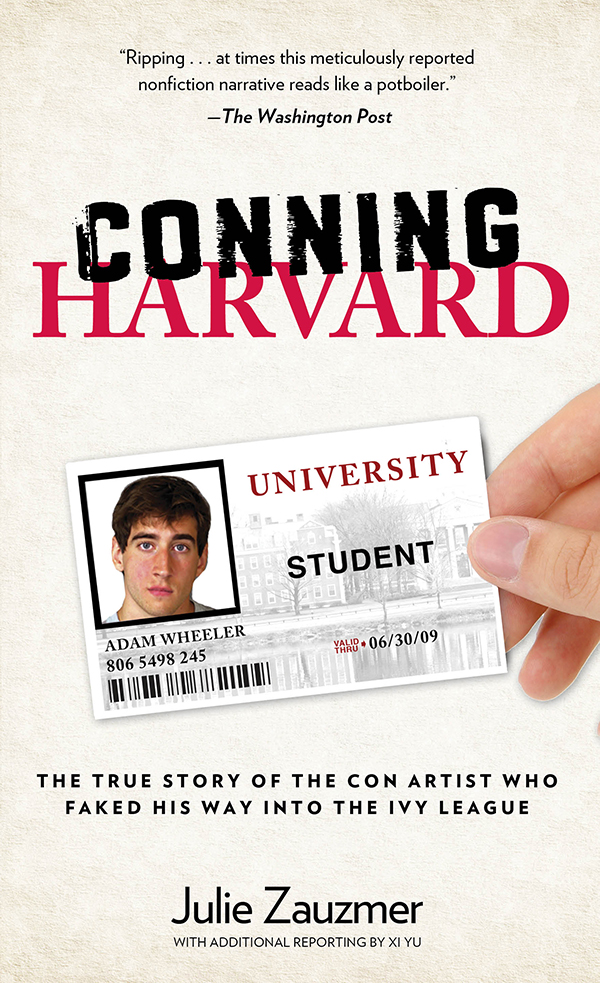

Conning Harvard : Adam Wheeler, the con artist who faked his way into the Ivy League / Julie Zauzmer ; with additional reporting by Xi Yu.

p. cm.

Summary: Conning Harvard tells the story of Adam Wheelers lie-filled path into Harvard, his compulsive conning of grant and scholarship boards after enrolling, and the eventual discovery of his fraudulent pastProvided by publisher.

ISBN 978-0-7627-8742-5 (hardback)

1. Cheating (Education)United States. 2. Wheeler, Adam (Adam B.) 3. Harvard UniversityStudents. 4. Harvard UniversityFunds and scholarships. 5. Swindlers and swindlingUnited States. I. Yu, Xi. II. Title.

LB3609.Z38 2012

378.198dc23

2012018145

CONNING HARVARD

To indicate as explicitly as possible the instances where the author could not know the exact words spoken by the participants in this story, some dialogue in this book appears without quotation marks. That dialogue should be read as the authors effort, based on statements made by one or more participants in each conversation, to reconstruct actual conversations in the manner most faithful to the likely words exchanged between the speakers.

This book chronicles an academic fraud of stunning proportions. Over a period of six years, Adam B. Wheeler tricked the smartest institutions in the country time and time again. He plagiarized application essays to get into one of the countrys best liberal arts colleges. He stole a Pulitzer Prize winners work to win a poetry prize. Then he took on Harvard Universitythe worlds most recognized institution of higher education, whose very name has meant prestige, privilege, excellence, and exclusivity for centuries.

Adam Wheeler was an expert forger and a skillful liar with seemingly few scruples about fabricating his academic credentials whenever the occasion arose. In snagging admission to Harvard, he unfairly attained an honor that millions of students worldwide dream of. In striving to scam institutions at the pinnacle of higher educationYale, Brown, Stanford, the Rhodes and Fulbright scholarships, and morehe astonished the nation with the story of his audacity. Many were outraged that he took a precious spot at Harvard that could have gone to an honest applicant, not to mention thousands of dollars in prizes that selection committees could have bestowed on deserving young scholars. Others were impressed by his skillful cons or even smugly amused to see Harvard outsmarted for once.

But whether one perceives him as the hero or the villain of his tale, this ultimately is not about Adam Wheeler. His fraudulent path is extraordinary, but on its own, his story is unimportant.

What is important is that high school students today face unprecedented pressure when it comes to college admissions. What is important is that as many as 14 percent of essays are plagiarized, 50 percent of transcripts are faked, and 90 percent of recommendation letters are forged among some groups of college applicants. What is important is that a generation of teenagers, raised in an educational system that emphasizes standardized testing and in an age of abundant technological options for untruthfulness, cheats on tests and homework with shocking frequency. As the pressure to win an ever-more-elusive ticket to a top-tier college ratchets higher each year, college admissions could be facing a crisis of honesty.

Far more than a victimless hoax, deception on an application is a violation of ethical and often legal precepts that affects the larger community. In the absence of integrity, a diploma is a meaningless piece of paper on the wall, a mockery of true intellectual achievement. To anyone who has ever been tempted to inflate some details on a rsum, to scribble answers on his hand or peek over her classmates shoulder, to pass off writing downloaded from the Internet as original, or to ink in a plus next to a grade on a transcriptthis book is a cautionary tale.

In the fall of 2009, life seemed to be going great for Harvard senior Adam Wheeler. His friends knew him as a lanky 21-year-old with muscles that showed his near-obsessive hours at the gym, a tall frame that made heads turn, and penetratingly blue eyes that drew women to him at parties. He was respected among his classmates as an academic all-star, working diligently for five or even six classes at a time on a campus where the norm was four. He had won awed recognition from his peers for the rare feat of winning Harvards top writing prize as a junior.

Though quiet, he was part of a large circle of friends who threw parties and played video games in their spacious suite. He had a steady girlfriend, an attractive Wellesley undergrad whom he had met the previous spring. He could frequently be found tossing a Frisbee across the courtyard of his dorm, Kirkland House.

To all appearances, Wheeler was in an enviable position. He was not only respected and well-liked among his peers, but also in a spot that students around the world pine for. He was a Harvard student, part of the minuscule percentage of applicants accepted each year. And in that rarified world of Harvard, Wheeler had essentially reached his peak. As his senior year started, he was on top of his game.

But one fall day in 2009, Wheeler was not playing Frisbee in Kirkland courtyard. Rather, he was indoors, sitting formally in an office, and the flawless identity he had built was about to come crashing down.

He did not know why the dean of Kirkland House had called him into his office, but a summons from the resident dean typically was not a good omen.

It was about his applications for the Rhodes and Fulbright scholarships, Dean Smith said. These were two of the most prestigious awards a graduating senior could win. Based on the strength of his application materials, Wheeler had a good shot at getting Harvards recommendation for one or both of them.

But what Dean David Smith said now was not, Congratulations. Instead, it was, You plagiarized your essay.

Wheeler froze. I must have made a mistake, he said. I didnt really plagiarize it.

Smith picked up two items and offered them to Wheeler. One was a copy of the essay Wheeler knew he had recently submitted to the judging committees, and the other was a crimson-colored book.

Smith had opened the book to a certain page. Centered at the top in capital letters, it said, By STEPHEN GREENBLATT. Wheeler knew the name: Greenblatt was his English professor from sophomore year, not to mention one of the worlds most famous Shakespeare experts. Then he glanced at the other piece of paper, his own essay.

The text is almost identical, Smith pointed out.

He started telling Wheeler about what would come next: a meeting with another dean. A hearing before the colleges disciplinary board. Intimidating procedures. He was invited.