Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

We hope you enjoyed reading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

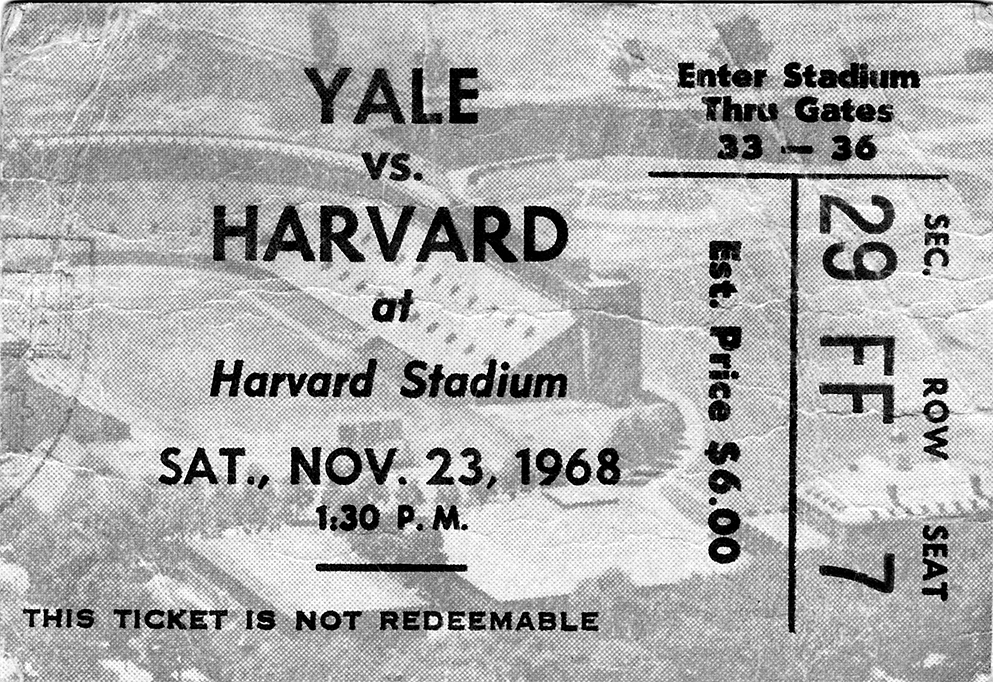

For my father, who taught us to stay until the end of the game. And for my brother Ned, who saved the ticket.

Prologue

I grew up going to Harvard football games in the 1960s. My father, a Harvard alumnus, worked in the colleges fund-raising office, and I lived a Harvard-saturated childhood. I swaddled my schoolbooks in glossy Harvard book covers; I thumbtacked my fathers old Harvard pennants along the molding of my bedroom wall; I listened to Veritas , his album of Harvard fight songs. Each evening when he came home from his office in Harvard Yard, Id fish a copy of the Crimson from his briefcase and read the sports page. On fall Saturdays, my brothers and I followed our parents up the concrete steps of Harvard Stadiumthe ancient, horseshoe-shaped hulk that looked like the Colosseum, but with a wedge missingand took our seats among the tweed-jacketed professors and bow-tied administrators near midfield. A few rows behind us, Harvards president, Nathan Pusey (Dad called him Nate), a thin-lipped man with a face as smooth and immobile as alabaster, sat with his wife, who knitted an endless series of crimson scarves as she watched the game.

When I was twelve, everything about Harvard football seemed outsized and heroic, from the monumental stadium to the musclebound players to the bands trampoline-size bass drum, reputed to be the largest in the world and guarded, according to my father, by the six strongest men at Harvard. (Not to mention the forty-foot-plus urinalssurely also the worlds largestthat lined the east and west walls of the mens room underneath the stands.) It mattered deeply to me whether Harvard won or lost, especially when it came to the Yale game, a clash of civilizations that seemed no less significant than that of Athens and Sparta. (Harvard, of course, was Athens.) I followed the action on the field as closely as the most avid alumnus, and far more closely than the Harvard students, who were so blas that when the cheerleaders shouted Gimme an H! I half expected them to shout back, Why should I? The moment the final whistle blew, my brothers and I raced onto the field to ask the players for their autographs and, if we were feeling brave, their sweat-stained chin straps.

In 1968, I was fourteen. I was no longer going to every Harvard home gameand I was certainly no longer running around on the field afterward asking players for their chin straps. I was letting my hair grow a little longer. I had bought my first pair of bell-bottoms (striped). On my turntable, Veritas had been replaced by Sgt. Pepper. I still devoured my fathers copy of the Crimson each night, though I read it as much for news of antiwar protests as for news of the football team. I still enjoyed Harvard football games, even if I now looked forward to the halftime show, in which the band made fun of LBJ, the Pentagon, and everyone over thirty, almost as much as to the game itself. And in mid-November when my father asked me whether I wanted to go to the Yale game, I said of course.

I

Two-a-Days

W hen Pat Conway decided to play football again, the one thing he didnt want to do was embarrass himself on the field. Now hed embarrassed himself before hed even gotten to the field. It was the first day of practice. In the locker room, listening to the other players joking and laughing as they put on their uniforms, he had pulled on his football pants and drawn the laces tight. But something didnt feel quite right. He snuck a glance at the players nearby and realized what it was. He had forgotten to put on his girdle, the thick cloth wrap that contained pads for his backbone and hips. The girdle went on before the pants. He looked around sheepishly, worried that someone had noticed, but everyone was busy lacing up shoulder pads or putting on cleats. Conway took off his football pants, cinched the girdle around his waist, and pulled the pants back on. He reached for a crimson stirrup sock and tugged it up his leguntil he realized that the socks, too, went on before the pants. He felt like a fool. Hed forgotten how to put on a football uniform. He unlaced his pants one more time.

Of the 117 candidates for the 1968 Harvard football team who returned to Cambridge on September 1 for three weeks of preseason practice, Pat Conway was, perhaps, the most unlikely. He was twenty-four years old, six years older than some of his teammates. He hadnt played football in more than three years. He knew almost no one on the team. Hed be trying out for safety, a position he had never played. Six months ago, he had been dodging mortar fire in Vietnam.

Conway had played football for Harvard before. A Sporting News high school All-American from Haverhill, Massachusetts, he had arrived in the fall of 1963 and quickly established himself as a star halfback on the freshman team. (On November 22, after his 48-yard touchdown run gave Harvard a 76 lead over Yale, he had been standing on the goal line, ready to receive the second-half kickoff, when the referee walked over and told him that President Kennedy had been shot. Although shaken, the hyper-competitive Conway pleaded with the official not to tell anyone else so they could finish the game.) Sophomore year, Conway started at fullback for the varsity, but he was floundering academically and Harvard put him on probation. The following autumn, falling still further behind, he left school, enlisted in the Marines, and was sent to Vietnam. While his Harvard teammates were playing Yale in November 1967, he had been digging foxholes at Khe Sanh Combat Base. His tour almost up, he had reapplied to Harvard for the spring semester. By the time his paperwork came through, more than 30,000 North Vietnamese troops had surrounded the base. It would be months before Conway was able to fly home.

Conway hadnt expected to play football when he returned to Harvard for his senior year. But that summer hed gotten a letter from Coach John Yovicsin saying he had a year of eligibility left; did he want to rejoin the team? Yovicsin told Conway they already had someonethe captain, Vic Gattoat right halfback, his favorite position. But they needed a safety. Conway said hed give it a try.

The last time he had touched a football was at Khe Sanh, before all hell broke loose. Someone had come across a battered old ball, and Conway and a few other marines had tossed it around for half an hour one afternoon. Conway never saw the ball again; he assumed it had blown up in a mortar attack.

He had no real expectation of making the team. But ever since hed started playing Pop Warner in the seventh grade, fall had meant football. Returning to college after almost three years away wouldnt be easy. Playing football might help him get back to his old life.

Next page