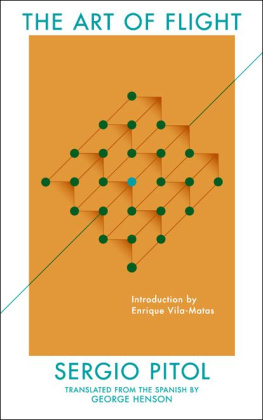

More praise for Sergio Pitol:

Pitol is not just our best living storyteller, he is also the strongest renovator of our literature.

LVARO ENRIGUE, author of Sudden Death

One of Mexicos most culturally complex and composite writers. He is certainly the strangest, most unfathomable and eccentric [His] voicereverberates beyond the margins of his books.

VALERIA LUISELLI, author of Faces in the Crowd

[The Art of Flight] is the most celebrated of Pitols novels It travels through readingsfrom Antonio Tabucchi to [William] Faulkner and Thomas Mannthrough cities, films, notebooks, and recordings, melancholy memories, hypnosis, and dreams.

Letras Libres

The bountiful work of [Sergio Pitol] is one of the most original in the Spanish language.

El Pas

[The Art of Flight] combines cultural density with autobiographical vigora landscape that is classic, desolate, ironic, parodic, and very lively.

CARLOS MONSIVIS

Deep Vellum Publishing

2919 Commerce St. #159, Dallas, Texas 75226

deepvellum.org @deepvellum

Copyright 2015 by Sergio Pitol

Originally published as El arte de la fuga in 1997 by Ediciones Era, Mexico City, Mexico Introduction Pitol baja la lluvia for The Art of Flight 2004 by Enrique Vila-Matas

Translation copyright 2015 by George Henson

First edition, 2015

All rights reserved.

ISBN: 978-1-941920-07-7 (ebook)

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CONTROL NUMBER: 2015930299

Esta publicacin fue realizada con el estmulo del PROGRAMA DE APOYO A LA TRADUCCIN (PROTRAD) dependiente de instituciones culturales mexicanas.

This publication was carried out with the support of the PROGRAM TO SUPPORT THE TRANSLATION OF MEXICAN WORKS INTO FOREIGN LANGUAGES (PROTRAD) with the collective support of Mexicos cultural institutions.

Cover design & typesetting by Anna Zylicz annazylicz.com

Text set in Bembo, a typeface modeled on typefaces cut by Francesco Griffo for Aldo Manuzios printing of De Aetna in 1495 in Venice.

Deep Vellum titles are published under the fiscal sponsorship of

The Writers Garret, a nationally recognized nonprofit literary arts organization.

Distributed by Consortium Book Sales & Distribution.

Contents

PITOL IN THE RAIN

By Enrique Vila-Matas

Life and literature are fused in Sergio Pitol. And I wonder now if there is anything more Cervantesesque than his passion for confusing life and literature. Somewhere in The Art of Flight, Sergio tells us that he is the sum of the books I have read, the paintings I have seen, the music I have heard and forgotten, and the streets I have walked. One is his childhood, his family, some friends, a few loves, and more than a few annoyances.

I think about the streets Ive had the chance to walk with him. There are streets, side streets, and backstreets traveled in Ashgabat, Veracruz, Caracas, Paris, Aix-en-Provence, Prague, Desvari, and Kabul. And Im reminded especially of a rainy day in Aix-en-Provence, where we went to pay tribute to Antonio Tabucchi. I remember the day because there was a pounding rain and Sergio was constantly losing his glasses; the latter was not at all unusual, his penchant for losing and then finding his glasses being legendary. That day he lost them several times, in various bookstores and cafs, as if that were a perfect antidote for not losing his umbrella. I recalled the day that Juan Villoro had found in Pitols tendency to lose his glasses a clue to illuminating new aspects of his poetics: Sergio writes in that hazy region of someone who loses his eyeglasses on purpose; he pretends that his originality is an attribute of his bad eyesight

For Villoro, Pitol does not seek to clarify but rather distort what he sees. In The Art of Flight, Pitol tells us that, on his first trip to Venice, back in 1961, he misplaced his glasses upon his arrival, he misplaced them while wondering if he would find death in Venice, death in the city of his ancestors. We also found death and mist, misplaced eyeglasses, and the compact fusion of life with literature on another rainy day, this time in Mrida, in the Venezuelan Andes. We had climbed to four thousand feet and, upon descending into the city, Sergio became alarmed because he thought his blood pressure was too high. We went into a pharmacy where a fourteen-year-old boy, who obviously didnt know what he was doing, took his blood pressure. You have five thousand four hundred pesos of blood pressure, the boy said. Sergio grew faint and startled. You should be dead, the boy added. Ay! Sergio screamed, and I can still hear today the echo of that scream unleashed in the middle of that Andean city. I explained to him that blood pressure was not measured in pesos and that, besides, the number didnt make sense, but Sergio remained peaked, and I ended up accompanying him to a nearby clinic wheretrue to his naturehe would forget his glasses. There, a nurse, who was dressed in an innocent yet almost obscene way (in an unbelievable miniskirt), after a brief examination, would only say that he was in no danger. None, she told him. Oh, Miss, Sergio added, its as if you had saved my life. Was that obscene nurse literature itself? Sergio always said that literature had saved his life. Shortly thereafter, he had to once again look for his glasses.

In these anecdotes of rainy days past lies the silhouette of his Cervantesesque life, since, as he says, Everything is all things. Reading him, one has the impression of being in the presence of the best writer in the Spanish language of our time. And to whomever asks about his style, I will say that it consists in fleeing anyone who is so dreadful as to be full of certainty. His style is to say everything, but to not solve the mystery. His style is to distort what he sees. His style consists in traveling and losing countries and losing one or two pairs of eyeglasses in them, losing all of them, losing eyeglasses and losing countries and rainy days, losing everything: having nothing and being Mexican and at the same time always being a foreigner.

Translated by George Henson

It was enough just to leave the train station and catch a glimpse from the vaporetto of the faades along the Grand Canal as they came into view to experience the feeling of being one step away from my goal, of having traveled years to cross the threshold, unable to decipher what that goal was and what threshold had to be crossed. Would I die in Venice? Would something arise that could in an instant change my destiny? Would I, perchance, be reborn in Venice?

I was arriving from Trieste; I had not searched for Joyces house or for traces of Svevo, nor had I done or seen anything that was worthwhile. I had arrived in the city the evening before, and as I attempted to find lodging in a hotel, an employee detected some anomaly or other in my visa, an error in the expiration date, I believe, which rendered my stay in the country illegal. I was allowed, reluctantly, to spend the night in the hotel lobby. Early that morning I caught the return train; when it stopped in Venice I decided to get off. It must have been seven in the morning when I first set foot on Venetian soil. I would spend the rest of the day there and continue on to Rome on the night express. It is written that misfortunes never come singly: after checking my bag at left-luggage I discovered I had lost my glasses; I searched my pockets and ran to the platform, hoping to find them on the ground, but the sea of travelers and porters bustling about forced me to abandon my search. Most likely, I thought, I had left them at the hotel in Trieste or on the train car I had left in such a rush.

Next page