INTERNATIONAL PRAISE FOR SERGIO PITOL

The Journey features one of the worlds master storytellers at work as he skillfully recounts his time as Mexicos Ambassador to Czechoslovakia in Prague and two fateful weeks of travel around the Soviet Union in 1986. From the first paragraph, Sergio Pitol dislocates the sense of reality, masterfully and playfully blurring the lines between fiction and fact.

This adventurous story, based on the authors own travel journals, parades through some of the territories that the author lived in and traveled through (Prague, Moscow, Leningrad, the Caucasus) as Pitol reflects on the impact of Russias sacred literary pantheon in his life, exploring the inspiration for his own novels and stories, and the power that literature holds over us all.

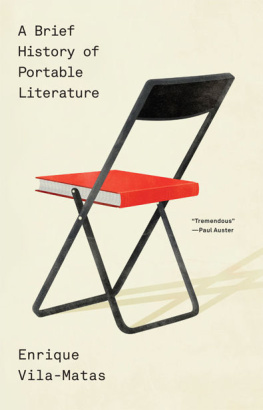

The Journey is the second work in Pitols groundbreaking and wholly original Trilogy of Memory, which won him the prestigious Cervantes Prize in 2005 and has inspired the newest generation of Spanish-language writers from Enrique Vila-Matas to Valeria Luiselli. The Journey represents the perfect example of one of the worlds greatest authors at the peak of his power.

International praise for Sergio Pitol:

Sergio Pitol is not only our best active storyteller, he is also the bravest renovator of our literature. LVARO ENRIGUE on The Journey

Pitol is unfathomable; it could almost be said that he is a literature entire of himself. DANIEL SALDAA PARIS, author of Among Strange Victims

Once again Pitol takes the reader on a transcendent adventure through geography and history. His voice learned and warm is the perfect companion on these flights, giving dramatic glimpses into the intellectual life of Soviet Prague one moment and inimitable insights into literature the next. The reader leaves the pages wiser, more enriched and able to fully appreciate Pitols status in Mexico and the rest of Latin America. MARK HABER, Brazos Bookstore

Reading him, one has the impressionof being before the greatest Spanish-language writer of our time. ENRIQUE VILA-MATAS, author of Dublinesque

Masterful. Dallas Observer on The Art of Flight

For lvaro Mutis, my brother in Russia

SERGIO PITOL, RUSSIAN BOY by lvaro Enrigue

There is a story that Sergio Pitol used to often tell when he still led a public life, and which he recorded in The Art of Flight. At the beginning of the eighties he spent a two-month vacation in Mexico City, after having lived for years in Barcelona, Warsaw, Budapest, and Moscow. At the time, he was 45 and had six or seven published books; he had translated Conrad and James and had been the editor of the legendary collection Los Heterodoxos, published by Tusquets in Spain and with a wide circulation throughout the Americas. Shortly after arriving in Mexico, he received a call from the PEN Club, inviting him to participate in a series of dialogues between writers of different generations a reading, followed by a public talk, between a veteran author and a novice. He accepted, and they announced that he would read with Juan Villoro. The event almost ended in disaster for Pitol: he thought, as he ascended the stage twenty-three years and a pile of books older than Villoro that he was to be the novice at the table. Nothing better describes Pitols eccentricity: he was a referential figure for an entire literature, and he still thought of himself as a promising writer.

It is this eccentricity sine qua non that allowed Pitol to become first a cult author and then the writer who reintroduced Mexican literatures beautiful secular tradition: authors of genreless books, more disposed to suggest a conversation than impose a monolithic idea of the world through a fiction populated with anecdotes and symbolic characters.

Read in the order published, Pitols books tell the story of a detachment. The author who began writing spellbinding yet conventional stories about the remote region of Mexico where he grew up gradually shed the themes and languages that gained prestige during the twentieth century: the peculiarity of a regional culture, the relevance of nationality, the Latin American soul in the solitude of exile.

Simultaneous to this detachment suicide in its time from the proven themes of regional writing, Pitol implemented a riskier experiment: to shed, too, the superstitions of literary form or perhaps expand them. Gradually, his books ceased to be novels or collections of short stories or essays, and became literary sessions in which the distance between fiction, reflection, and memory is irrelevant. Books that are everything at the same time what his contemporary Salvador Elizondo called, half philosophically, half ironically, books to read.

At the time of the publication of The Art of Flight and The Journey, the gesture to forswear genre was seen as defiantly post-modern: in order for writing to be total, it had to dispense with the market-related conventions that asphyxiated Latin American literature during the late twentieth century, in which the large publishing houses seemed to have imposed a short-sighted and dull literary taste as the only option for bookstores.

Over time, it is possible to see clearly that while it is true that the acclaim both books received was unexpected, it is also true that Pitol was not acting like a desperate innovator, rather like the attentive reader of a tradition that always found literary genres claustrophobic. Nor did the books of Martn Luis Guzmn, Nellie Campobello, Jos Vasconcelos, and Alfonso Reyes founders of Mexicos literary modernity possess a clear genre. From the same generation as Sergio Pitol, authors like Margo Glantz, Alejandro Rossi, or Salvador Elizondo himself, all brilliant and relatively unknown outside of Latin America, continued to stress that the countrys most resilient literary production consisted of writings free of generic conventions.

Sergio Pitols later books, then, are not capricious. They are grounded in a tradition and are the product of a process in which he has worked in a consistent and serene way over the last twenty years: human experience lacks value until it is transformed into writing; but if the obtuse geometry of genre writing is imposed onto that, its irrational foundation is betrayed. Inspiration, Pitol notes in The Magician of Vienna, is the most delicate fruit of memory. It is not a new idea: it lies at the bottom of the writing of St. Augustine, Montaigne, and Camus. For the author, the genius that moves literature is correspondence: experience, as Pitol himself says, is just a set of fragments of dreams not altogether understood.

This is why The Art of Flight begins with the myopic description of Venice: in order to see what has value in the world, one must leave their everyday eyeglasses on the desk. The reality is there, but is only meaningful when it is removed by the erasure that implies selecting and assembling a series of episodes, readings, notations. This is also why The Journey includes essays, but also diary pages, anecdotes, and stories so circular that they could not be entirely true but are related as if they were. Literary imagination, according to Pitol, does not progress in the rational order that the novel, essay, or short story demand. It is more like a sea sponge than a freeway. It is a solid block, without a basis, but full of inner paths that connect ideas, notes, invented memories.

The beginning of The Journey could not be more classic. The author, tired and a bit sick, locks himself away to write in a sort of tropical Montaignes tower: a modest, cultured, and provincial city on the Gulf of Mexico. He recalls his years as ambassador in Prague and notices that his favorite city of the many in which he has lived is the only one about which he has never written anything. Surprised, he checks his diaries from the time and discovers a hole: they contain only notes about meetings, readings, and petty office problems not a word about his outings through the never-ending city, its splendid museums, its powerful cultural life. What he does find in his notebooks, however, is a travel diary to Russia that, over time, grew in significance: it records the moment of the Soviet Thaw.