Klitgaard - Tropical Gangsters

Here you can read online Klitgaard - Tropical Gangsters full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: London;Guinea Equatorial, year: 1991;2010, publisher: I.B. Tauris, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

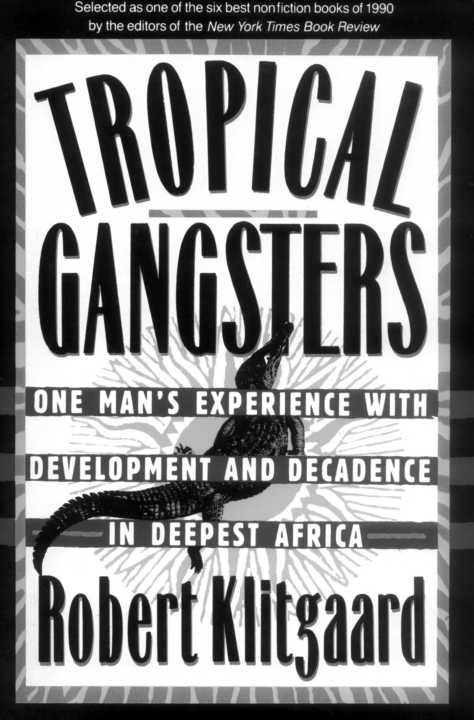

- Book:Tropical Gangsters

- Author:

- Publisher:I.B. Tauris

- Genre:

- Year:1991;2010

- City:London;Guinea Equatorial

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Tropical Gangsters: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Tropical Gangsters" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Tropical Gangsters — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Tropical Gangsters" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

I

OTHER BOOKS BY ROBERT KLITGAARD

Controlling Corruption Elitism and Meritocracy in Developing Countries Data Analysis for Development Choosing Elites

ROBERT KLITGAARD

For Mom and Dad, who taught by example how to love.

Qv OU say you have spent two and a half years with one tribe," the great French anthropologist Marcel Mauss once remarked to a colleague. "Poor man, it will take you twenty years to write it up."1

Sometimes I have feared that Mauss was right: sometimes the "writing up" has seemed endless. Fortunately, however, the present book does not have the aim of "representing a culture," the intimidating task Mauss set for himself and his students. Instead, it tries to tell a story and capture a mood, a story and a mood that I think have importance beyond the borders of the tiny country where I spent my two and a half years.

The story concerns a poor country trying to reform its economy. Today a movement toward the free market is sweeping the globe. Despite all the drama in China and the Soviet Union and especially Eastern Europe, it is Africa that has been at the forefront of change. More than thirty African countries have undertaken major economic reforms in the past half-dozen years, one of them being Equatorial Guinea. Its story, Africa's story, has implications beyond the continent.

Equatorial Guinea is one of the most backward countries in the world. But an extreme case may help us see more clearly what is happening in more typical instances. As in most other countries carrying out tree market reforms, Equatorial Guinea's leaders have not always known quite how to make the new strategy work-or, in some cases, whether they should really try. This ignorance and reluctance, though extreme, are in many ways prototypical, and they raise general questions. How does one go about assessing an economy's strengths and weaknesses? How does one go about developing the institutions needed to make free markets work? And how can one help a recalcitrant, inefficient, sometimes corrupt government move forward? These questions are at the heart of my story; and they are relevant to much of the world.

Another part of my story concerns the role of international aid. In Africa, the key perpetrators of change have been the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund. In the past decade their leverage has grown mightily, to the point where they are accused of neo-imperialism. My story involves a World Bank project that hopes to transform a ruined economy, a project with about one seventh of the country's gross national product under its control. It was a project I administered, working with a team of three Equatoguinean ministers. The country wouldn't get this money unless it agreed to a host of policy changes and would not get more unless our team developed a detailed economic strategy. New questions arise. What are the creative possibilities and the inherent limitations of such outside assistance? What are the tensions between aid and dependency, between benevolence and autonomy? And how would you have gone about the task-how would you have acted-if you were me?

The story I tell raises all of these difficult questions. The mood I try to convey is harder to summarize, and mood may itself be the wrong word.

Africa can be a brutal and paranoid place, and it is the world's economic basket case. But it also has smiles and guitar solos and an awesome ability to persevere. One can be overwhelmed by Africa's problems at one hour and be enthralled by the cultures and natural beauty in another. Africans themselves are, I believe, caught in these radical swings in emotion and perception. Intimacy can soon be followed by intimidation, careful thought by thoughtless rage, discipline by dissipation. Outsiders may perceive in all of this nothing more than African inconstancy and confusion, even deceit. But I feel it and felt it differently. The environment of today's Africa-broadly interpreted to include not only nature but knowledge and tradition and lacks thereof-puts one constantly at the edge, heightens every sense and every moral dilemma, renders one perennially unsure of what comes next. Can we call this a mood?

It is in this context that economic and political changes are taking place in Africa. Distrust, delay, exaggeration, ignorance, exuberance: all enter in unanticipated ways. They complicate the usual questions of reform-the what-to-do and the administrative how. And so the story and the mood interact. The details of their interplay are no doubt everywhere unique, and yet-though I am acutely aware of the limitations of the account presented here-I hope that sharing one particular instance of economic reform may provoke by comparison and contrast an improved understanding of others.

The reader will, I hope, discern throughout this account my sense of privilege in having been able to live and work in Equatorial Guinea. My friends and colleagues there-many of whom could not for reasons of space or story line be included in the book-enriched my life, and my debts to them are immense. Since these debts are of friendship as much as of instruction, I must hope that they were partly discharged in the course of incurring them, for certainly this book alone is insufficient repayment.

The characters and events that appear here are all true, though I have changed most names and a few details to mitigate possible embarrassment. The character I call Saturnino has a particularly sensitive story, and I shared with him the parts of the penultimate draft that told it. He agreed to its inclusion on grounds that "it will help the country." But later he asked that details of his own identity be further disguised-though he admitted that, even so, insiders would know who he was. I have followed his wishes.

Saturnino is the only Equatoguinean who read earlier drafts of this account-mostly because language and logistics made sharing difficult. But other friends and colleagues have kindly read and criticized various stages of the writing up. Foremost among them is Phoebe Hoss of Basic Books, whose extraordinary pains with the manuscript led to major improvements, though perhaps not as many as she hoped. Martin Kessler of Basic Books saw in scraps I showed him the potential for a book, encouraged me, and helped improve the final product. I am also grateful for the advice and encouragement of Will Adamopoulos, Mahenou Agha, Cathy Bartz, Tora K. Bikson, Marilyn Cvitanic, Roger M. DiJulio, Laurence A. Dougharty, Joseph Giampa, Gus Haggstrom, James Hammitt, Cord Jakobeit, Mildred S. Klitgaard, Robert M. Klitgaard, Marc Lindenberg, Anne Marchot, Richard E. Neustadt, H. Lindsey Parris, Jean Parris, John Rolph, Michael Schiffer, Lisa Simonson, Geralyn White, and Maureen A. White. Most of the first draft was written with Geralyn White in mind and heart.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Tropical Gangsters»

Look at similar books to Tropical Gangsters. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Tropical Gangsters and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.