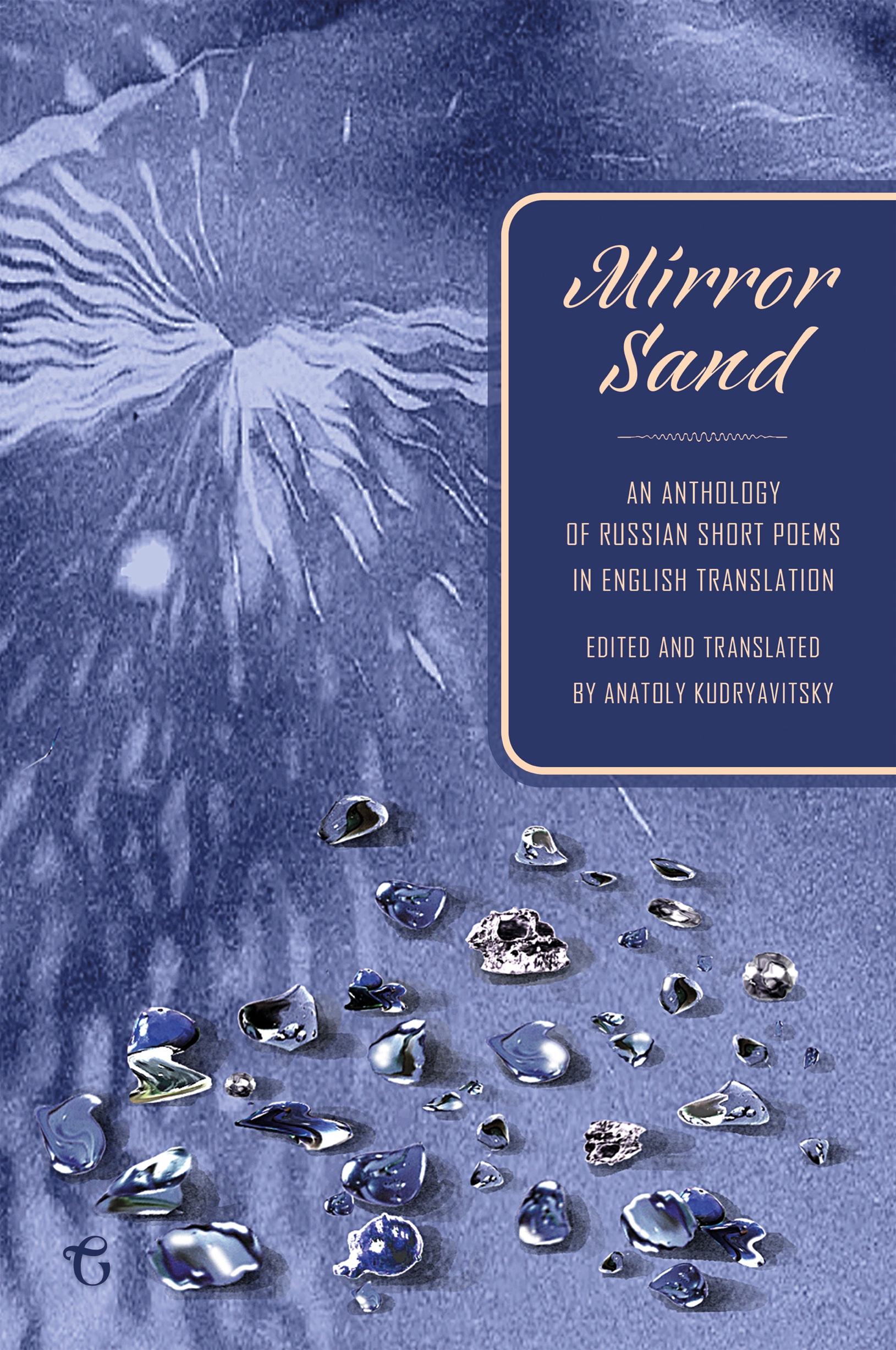

MIRROR SAND

An Anthology of Russian Short Poems in English Translation

Translated by Anatoly Kudryavitsky

MIRROR SANDAn Anthology of Russian Short Poems in English Translation (English only edition ) Edited, translated, and introduced by Anatoly Kudryavitsky, this anthology presents Russian short poems of the last half-century. It showcases thirty poets from Russia, and displays a variety of works by authors who all come from different backgrounds. Some of them are well-known not only locally but also internationally due to festival appearances and translations into European languages; among them are Gennady Aigi, Gennady Alexeyev, Vladimir Aristov, Sergey Biryukov, Konstantin Kedrov, Igor Kholin, Viktor Krivulin, Vsevolod Nekrasov, Genrikh Sapgir, and Sergey Stratanovsky. The next Russian poetic generation also features prominently in the collection. Such poets as Tatyana Grauz, Dmitri Grigoriev, Alexander Makarov-Krotkov, Yuri Milorava, Asya Shneiderman and Alina Vitukhnovskaya are the ones Russians like to read today. This anthology shows Russia looking back at itself, and reveals the post-World-War Russian reality from the perspective of some of the best Russian creative minds.

Here we find a poetry of dissent and of quiet observation, of fierce emotions, and of deep inner thoughts . Introduction copyright Anatoly Kudryavitsky, 2018 English translations Anatoly Kudryavitsky, 2006, 2018 Original Russian-language poems their individual authors, 2018 This collection copyright Glagoslav Publications, 2018 Front cover image Jassemine Darouiech, 2018 Cover and layout design by Max Mendor www.glagoslav.com ISBN: 978-1-91141-474-2 ( Ebook ) A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library . This book is in copyright. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser .

Contents

Acknowledgments

Grateful acknowledgement is made to the editors of the following, in which a number of these translations, or versions of them, originally appeared :

Haydens Ferry Review, Cyphers, Das Gedicht, Poetry Ireland Review, The SHOp, Shot Glass Journal, SurVision, Public Pool, Four Centuries, World Poetry Almanac (Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia),

A Night in the Nabokov Hotel anthology (Dedalus Press, 2006 ). Some of these poems, in English translation, were first broadcast on RT Radio . Every effort has been made to trace the holders of the copyright to the works by Vladimir Burich, Mikhail Finerman and Arkady Tyurin, and to obtain permissions to reproduce their works.

Please do get in touch with any enquiries or any information relating to their poems or the rights holders .

Introduction

A saying has it that Russia produces more than it can consume locally. Should this refer to Russian poetry? Western readers are well acquainted with poetry written in that country over the last three centuries, from Alexander Pushkin to Anna Akhmatova, mostly through translations. Some other Russian poets, including Vladimir Nabokov and Joseph Brodsky, felt at home at writing in English. This book offers an opportunity to hear a few newer voices . As Vladimir Nabokov once put it, Literature belongs to the department of specific words and images rather than to the department of general ideas.

Unfortunately, the general idea in Communist Russia was to encourage and publish only those writers who supported and even glorified the regime. It was Government policy, especially strict after the last world war. It is inconceivable now that any European poet could write a paean for the President of the European Council, but we have to bear in mind that in Communist Russia, even in the 1980s, this sort of poetry was a commonplace. Other poets ran the risk of being treated with suspicion by each and every literary vigilante. Should we be surprised by Marina Tsvetayevas line: All the poets are Jews ? After Pasternak, Russian poetry sustained a pause, the late Genrikh Sapgir used to say. It was destined to be a long pause.

In fact, the generation of Russian writers that emerged in the early 60s grew up reading and studying in college Russian poetry from the 1920s. Some of them were particularly inspired by Boris Pasternak and Osip Mandelstam, others by Velimir Khlebnikov and other Russian Futurist poets. What appeared in Soviet fat magazines in those times were, to quote Anna Akhmatova, rhymed editorials, or otherwise third-rate imitations of Symbolist poetry from the late nineteenth century . In these circumstances some Russian poets chose to refrain from publishing anything openly, while others were banned from publishing. Writing into the table became customary for them. Many of them explored the possibilities of so-called open poetry.

By stripping their pieces down to a most basic expression, and outlawing most literary devices or even emotional colouring, they focused their attention on individual words, or even on fragments of those words and sound units from them. This style was later defined as minimalism. One can trace the sources of modern-day minimalist texts to Dadaist, Surrealist, Concrete and even Zen poetry, and it definitely displays parallels to the visual arts. Minimalist poets focused on bare words or phrases, sometimes rearranging them on the page so that their most basic and individual properties disclosed something unexpected about themselves . The work of these poets wasnt minimalist in the sense that they had little to say; quite the contrary, it captured the frustration, suppressed ambitions and hidden energy of several generations of Russian people. As Vassily Kandinsky once put it, Even absolute silence is a loud speech.

Joseph Brodsky in one of his lectures compared Mark Strand and Charles Simic, well-established American poets of silence, as he called them, to unofficial Russian poets who had to dwell in silence, due to having no other literary space. Rea Nikonova, a poet from the South of Russia, even produced a catalogue of different kinds of silence. She knew very well what she was talking about as she first lived in Yeysk, a small Russian town on coast of the Azov Sea and then on the other shores of exile, in Germany, until her untimely death . In the 1960s and 1970s, Genrikh Sapgir, Vsevolod Nekrasov and Igor Kholin were the most prominent among the Moscow writers that came to be associated with the now well-known Lianozovo group. These poets sought out new models and positions, and exploited the possibilities of inserting common speech directly into their texts. Each of them had a Dostoyevskian eye for everyday Russian life, which made their work immediately accessible.

No wonder that they at once found themselves uncomfortable with authority and orthodoxy, and also with the authorities and the Orthodox Church, suppressed under the Communists but still powerful, as far as the minds of the Russians were concerned. These were real rebels, unlike a few other Russian poets who enjoyed virtual pop-star status, unthinkable if transposed to other parts of Europe. In reality, the latter were far from any sort of protest against Soviet totalitarianism and therefore could not be regarded as anything else but naughty children of the regime . The idea of a cultural centre was particularly dispiriting for those who were geographically based far from Moscow and therefore felt marginalised. Gennady Aigi and Arvo Mets are typical of the rise of poets who settled down in the Russian capital and preferred to write in Russian rather than in their mother tongues, in this case respectively Chuvash and Estonian. The sources of their poetry were different; no wonder that their verse sounded so fresh and enriched the Russian language to such a great extent.

Next page

![Dzhejms CHejz - The Mirror in Room 22 [short story]](/uploads/posts/book/853161/thumbs/dzhejms-chejz-the-mirror-in-room-22-short-story.jpg)