Other Books by David Hinton

WRITING

Desert (Poetry)

The Wilds of Poetry (Essay)

Existence: A Story (Essay)

Hunger Mountain (Essay)

Fossil Sky (Poetry)

TRANSLATION

The Selected Poems of Tu Fu: Expanded and Newly Translated

No-Gate Gateway

I Ching: The Book of Change

The Late Poems of Wang An-shih

The Four Chinese Classics

Classical Chinese Poetry: An Anthology

The Selected Poems of Wang Wei

The Mountain Poems of Meng Hao-jan

Mountain Home: The Wilderness Poetry of Ancient China

The Mountain Poems of Hsieh Ling-yn

Tao Te Ching

The Selected Poems of Po Ch-i

The Analects

Mencius

Chuang Tzu: The Inner Chapters

The Late Poems of Meng Chiao

The Selected Poems of Li Po

The Selected Poems of Tao Chien

The Selected Poems of Tu Fu

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

4720 Walnut Street

Boulder, Colorado 80301

www.shambhala.com

2019 by David Hinton

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Shambhala Publications is distributed worldwide by Penguin Random House, Inc., and its subsidiaries.

Ebook design adapted from printed book design by Steve Dyer

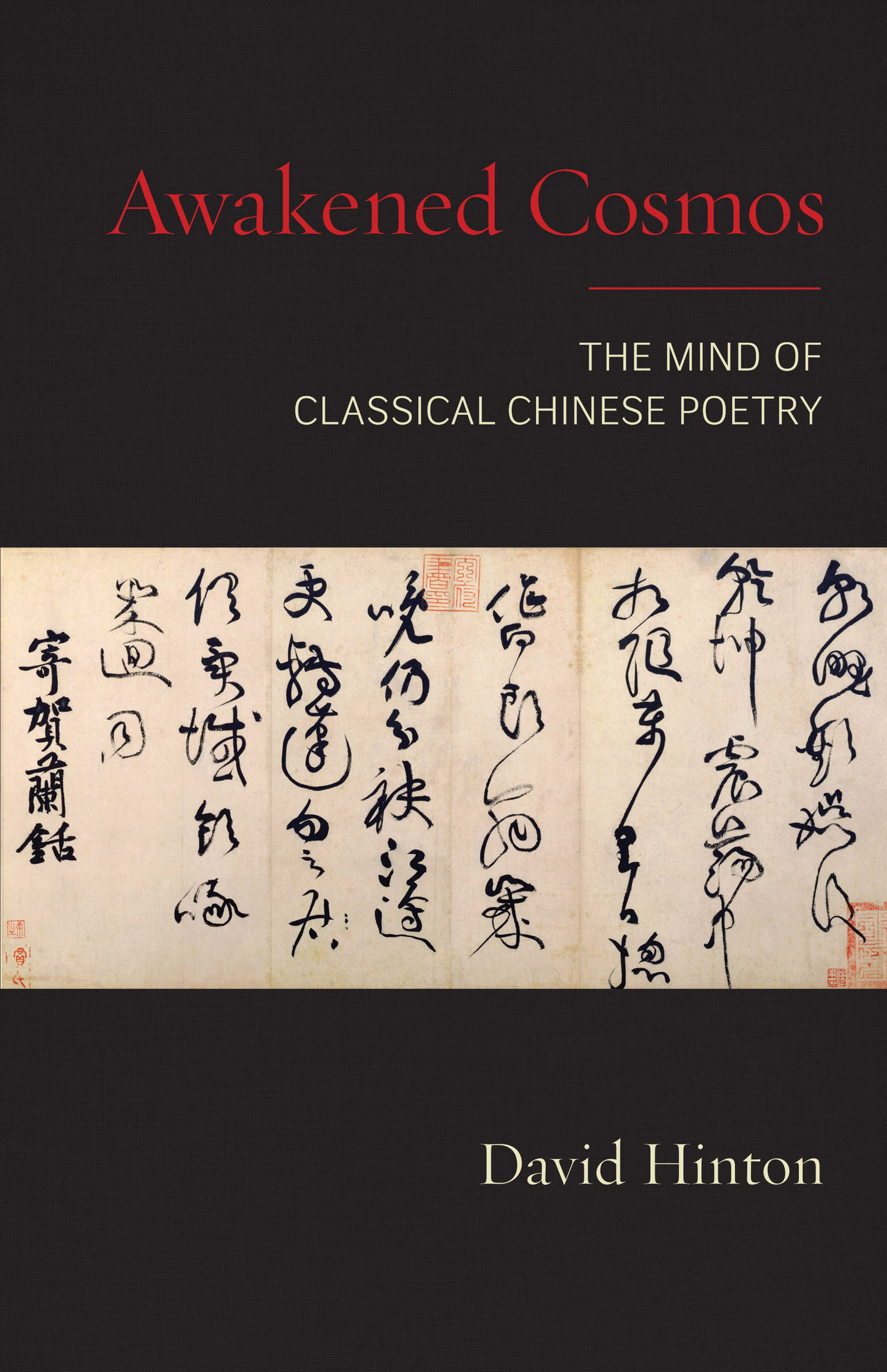

Cover art: Verses by Tu Fu by Huang Ting-chien (10451105). Provided by the Palace Museum.

Cover design by Daniel Urban-Brown

L IBRARY OF C ONGRESS C ATALOGING - IN -P UBLICATION D ATA

Names: Hinton, David, 1954 author. | Container of (work): Du, Fu, 712770.

Poems. Selections. | Container of (expression): Du, Fu, 712770. Poems.

English. Selections.

Title: Awakened cosmos: the mind of classical Chinese poetry / David Hinton.

Description: First edition. | Boulder: Shambhala, 2019. | English and Chinese.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018058003 | ISBN 9781611807424 (paperback: alk. paper)

eISBN9780834842403

Subjects: LCSH: Du, Fu, 712770Criticism and interpretation. |

Chinese poetryTang dynasty, 618907History and criticism.

Classification: LCC PL 2675 . H 56 2019 | DDC 895.11/3 DC 23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018058003

v5.4

a

Acknowledgments

Generous support from UPAYA ZEN CENTER was instrumental to the creation of this book.

Contents

Introduction

P OETRY IS THE C OSMOS AWAKENED TO ITSELF . Narrative, reportage, explanation, idea: language is the medium of self-identity, and we normally live within that clutch of identity, identity that seems to look out at and think about the Cosmos as if from some outside space. But poetry pares language down to a bare minimum, thereby opening it to silence. And it is there in the margins of silence that poetry finds its deepest possibilitiesfor there it can render dimensions of consciousness that are much more expansive than that identity-center, primal dimensions of consciousness as the Cosmos awakened to itself. At least this is true for classical Chinese poetry, shaped as it is by Taoist and Chan (Zen) Buddhist thought into a form of spiritual practice. In its deepest possibilities, its inner wilds, poetry is the Cosmos awakened to itselfand the history of that awakening begins where the Cosmos begins.

In that beginning, there was neither light nor spaceand for consciousness, they are the essentials. During its first moments, the Cosmos was a primordial plasma of subatomic particles. This plasma expanded and cooled until the particles could bond to form the lightest atoms, hydrogen and helium, whereupon the Cosmos became transparent to radiation such as light. Eventually, hydrogen and helium began condensing into proto-galactic clouds under the gossamer influence of gravity, and chance fluctuations in the density of these clouds led some local areas to intensify their condensation until pressure and heat became so fierce that hydrogen atoms began fusing together. In that process, which can only be described as magical, stars were born. And with those stars came the elemental dimensions of consciousness: space and light and the visible.

Those dimensions began to evolve. The stars grew old, like anything else, and died. In the furnace of their old age and explosive deaths, they forged heavier elements and scattered them into space, forming nebular clouds that in turn condensed into new stars. It is the heartbeat of the Cosmos, this steady pulse of stellar birth and death, gravitys long swell and rhythm of absence and presence, presence and absence. And in the third star-generation, our planet was formed, rich in those heavy elements. It cooled and evolved until eventually water appeared: hydrogen, created during the original cosmic expansion, combining with oxygen, one of those heavier elements created in the cauldrons of dying stars. Water formed mirrored pools in hollows on the planets rocky surface, and in these pools the Cosmos turned toward itself for the first time here. It became aware of itself in those mirrored openings deep as all space and light, deep as the visible itself.

Living organisms evolved and eventually developed receptors that allowed them to sense whether or not light was present. Those light receptors provided decisive selective advantages, and so developed into more and more sophisticated forms. The lens evolved as a means to concentrate light on receptor cells, thereby making creatures more sensitive to weak light. This innovation eventually led to image-forming eyes, which combine a lens with highly specialized receptor cells. And with that, the Cosmos turned toward itself once again, eventually giving shape to consciousness, that spatiality the eyes mirrored transparency conjures inside animals. It was a miraculous development: the material universe, which had been-perfectly opaque, was now open to itself, awakened to itself!

Although ancient Chinese poets and philosophers didnt describe it in these scientific terms, this same sense of consciousness as the Cosmos open to itself was an operating assumption for themthough perhaps here existence is a better word than Cosmos, as it suggests the sense of all reality as a single tissue. This existence-tissue is the central concern of Lao Tzus Tao Te Ching (sixth century B . C . E .)the seminal work in Taoism, the spiritual branch of Chinese philosophy that eventually evolved into Chan Buddhism. Lao Tzu called that existence-tissue Tao, which originally meant Way, as in a road or pathway. But Lao Tzu used it to describe the empirical Cosmos as a single living tissue that is inexplicably generativeand so, female in its very nature. As such, it is an ongoing cosmological process, an ontological pathway by which things emerge from the existence-tissue as distinct forms, evolve through their lives, and then vanish back into that tissue, only to be transformed and reemerge in new forms. It is a majestic and nurturing Cosmos, but also a refugee Cosmos: all change and transformation, each of the ten thousand things in perpetual flight, always on its way somewhere else.