Acknowledgments

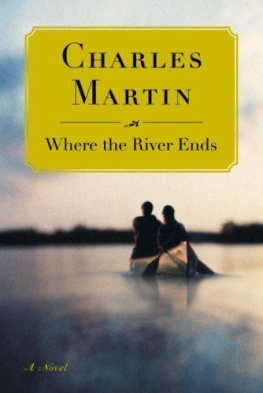

Books, like rivers, have many origins. The headwaters of this narrative are two actual journeys, our December 2008 family paddling vacation in Costa Rica and my eleven-day trip down the Santee in March and April 2009. These trips offered the concrete outlines of the present narrative, but various texts also contributed to its texture and meaning.

In January 2006 I discovered a childrens picture book published in 1941 called Paddle-to-the-Sea at the South Carolina Book Festival, and I began to imagine a trip from my backyard to the ocean. Written and illustrated by American author and artist Holling C. Holling, Paddle-to-the-Sea tells the story of a boy who carves a toy canoe with a wooden Indian paddling it. On the canoes bottom the boy writes, Please put me back in the water. I am Paddle-to-the-Sea, and drops it in Canadas Lake Nipigon. Paddle-to-the-Sea travels all the Great Lakes and finally reaches the Atlantic Ocean. Along the way the tiny, carved toy canoeist encounters and endures a sawmill, storms on the Great Lakes, a shipwreck, currents, a forest fire, a plunge over Niagara Falls, and large seagoing ships.

Paddle-to-the-Sea made an impact in the literary world and was recognized as a Caldecott Honor Book in 1942. Some argue it is an early ecology book because it introduced a whole generation of children to the idea of watersheds. Twenty years later, a film (also called Paddle-to-the-Sea) was produced by the National Film Board of Canada and directed by Bill Mason of Path of the Paddle fame. It too had its success when it was nominated for an Oscar.

The tributaries feeding my narrative through the years of composition are various as its original sources. I consulted a variety of primary and secondary works for the factual and literary information: Robert Millss Atlas of the State (1825); John Pendleton Kennedys Horse-Shoe Robinson (1852); J. D. Baileys The History of Grindal Shoals (1921); Arthur Henry Hirschs The Huguenots of Colonial South Carolina (1928); Julia Peterkins Scarlet Sister Mary (1928); W. J. Cashs Mind of the South (1941); Henry Savages River of the Carolinas: The Santee (1956); William P. Cummings The Southeast in Early Maps (1958; revised and enlarged by Louis De Vorsey Jr., 1998); Archibald Rutledges Deep River: Collected Poems (1960); Bobby Gilmer Mosss The Old Iron District (1972); Walter Edgars History of Santee Cooper, 19341984 (1984) and South Carolina: A History (1998); Mike Hembree and Paul Crockers Glendale (1994); Billy Kennedys The Scots-Irish in the Carolinas (1997); David Taylors The Ned Beatty and Me in Upcountry Review (Fall 1999); Rick Basss The Call of the Congaree in Sierra Magazine (July/August 2002); Robert F. Durdens Electrifying the Piedmont (2003); Susan Millar Williamss biography of Julia Peterkin, A Devil and a Good Woman Too (2008); Vennie Deas-Moores Columbias Riverbanks: A History of Its Waterways (2008); and Robert Kapschs Historic Canals and Waterways of South Carolina (2010).

I also used various Internet sources, common and obscure, including online applications for the National Register of Historic Places for the sites in the piedmont such as Pinckneyville, the Broad Rivers Fish Dam Ford, and the Lockhart Canal; I found The Narrative of Richard Jones, a Boatman on the Broad River in an interview conducted in Union County, South Carolina, by the Federal Writers Project on July 9, 1937; the New York Times provided numerous articles about the Santee basin and particularly the rise of nuclear power in South Carolina in the 1960s and 1970s; and as noted in the narrative, the South Carolina Gazetteer was the source for my primary travel maps.

Above all, Id like to thank Venable Vermont for paddling with me on the first leg of trip and for his river knowledge, friendship, support, Dutch-oven meals, spirit, colon blow, and world-class stories of rivers and river running; Steve Patton for his river journal, his friendship, his J-stroke, and for accompanying me on the final leg of a good river trip; Chris Cogan and Tom Byars for allowing the tables to be turned as in this narrative they become characters in my movie; Bernie Dunlap for predeparture stories about his uncle Henry Savage and keeping the Good Ship Wofford College on stable course; Woffords academic dean David Wood for his support; Ron Robinson for the blessing; Cathy Conner for her wizardry with copying machines; George Fields for a lift down the hill to Grindal Shoals and good Daniel Morgan stories; Christine Swager for Revolutionary War context and for reading the Grindal Shoals section of the manuscript; Montana Stambaugh and the late Louie Philips for providing a dry porch for the river voyagers the first night on the river; Gray Cecil for logistical support; Zubie, Margie, and their girls for putting us up (and putting up with us) on our Columbia layover; Drake Perrow for the Santee shuttle; Toms parents, the Byarses, for feeding us and putting us up at Murrells Inlet on the night after we finally crawled off the river; Steve Jordan at Liquid Logic for a good deal on a sit-on-top kayak, even though I didnt end up using it; John Vermont for reading and river advice; Frank, Ken, Dunk, and Grady for our tune-up trip; Steve Liebig and Tom Visnius for reading the manuscript in the late stages and making important suggestions; Lus Fernando Allen at the Hotel Interamericano in Turrialba, Costa Rica, for helping us recover after our tragic river trip; Stuart Stevens for listening to my Costa Rica story; Laura BarbasRhoden for translating articles about Jeremys death; Fred Parrish, as always, for his vast knowledge of all things natural in the watershed; Bob Cumming for sending me a copy of his fathers book The Southeast in Early Maps and taking me to the Davidson College map room to see the originals; Wofford College archivist Philip Stone for first pointing me toward Duane A. Stobers 1969 River Voyageurs journal; Alan Stokes at the Caroliniana Library at the University of South Carolina for helping me sort through the Henry Savage records and letters; Susan Toms in Spartanburg County Librarys Kennedy Room for sending me the March 31, 1880, piece in the Carolina Spartan about the Garner Brothers paddling from Skull Shoals to the sea; to UGA Presss Laura Sutton, Jon Davies, and all for the support they have shown me; and, finally, many thanks to my wife, Betsy, as always, for everything.

The Blessing

The BlessingFrom his spot at the top of the hill, Venable Vermont, with his long, salt-and-pepper beard, looked like John Brown or John Muir back from the dead. The late March air was crisp but not cold. Fifty-five degrees with a forecast of rain, Venable called to me in the yard below, where I had gathered my paddling gear. The long-term weather report looked ominous as well. Weather.com showed cold fronts stacked up like green blobs one after another all the way west from South Carolina to California. Years had passed since Id seen such a wet forecast. I watched as the big Alaskan picked up his dry bag and small lunch cooler and carried them toward the river. Then he came back for his boat.

Venable hefted his Dagger canoe up Northwoods-portage style, balancing it on his shoulders with his head inside, and took off down the trail. All I could see were his legs, his lower torso, his hands balanced on the upside-down gunnels, and the bottom swell of his huge beard bouncing with each step. I watched as my partner for the first eight days of my paddle to the sea descended our backyard trail. I fell in behind, carrying down the rest of my own gear.

The Blessing

The Blessing