Contents

Guide

Page List

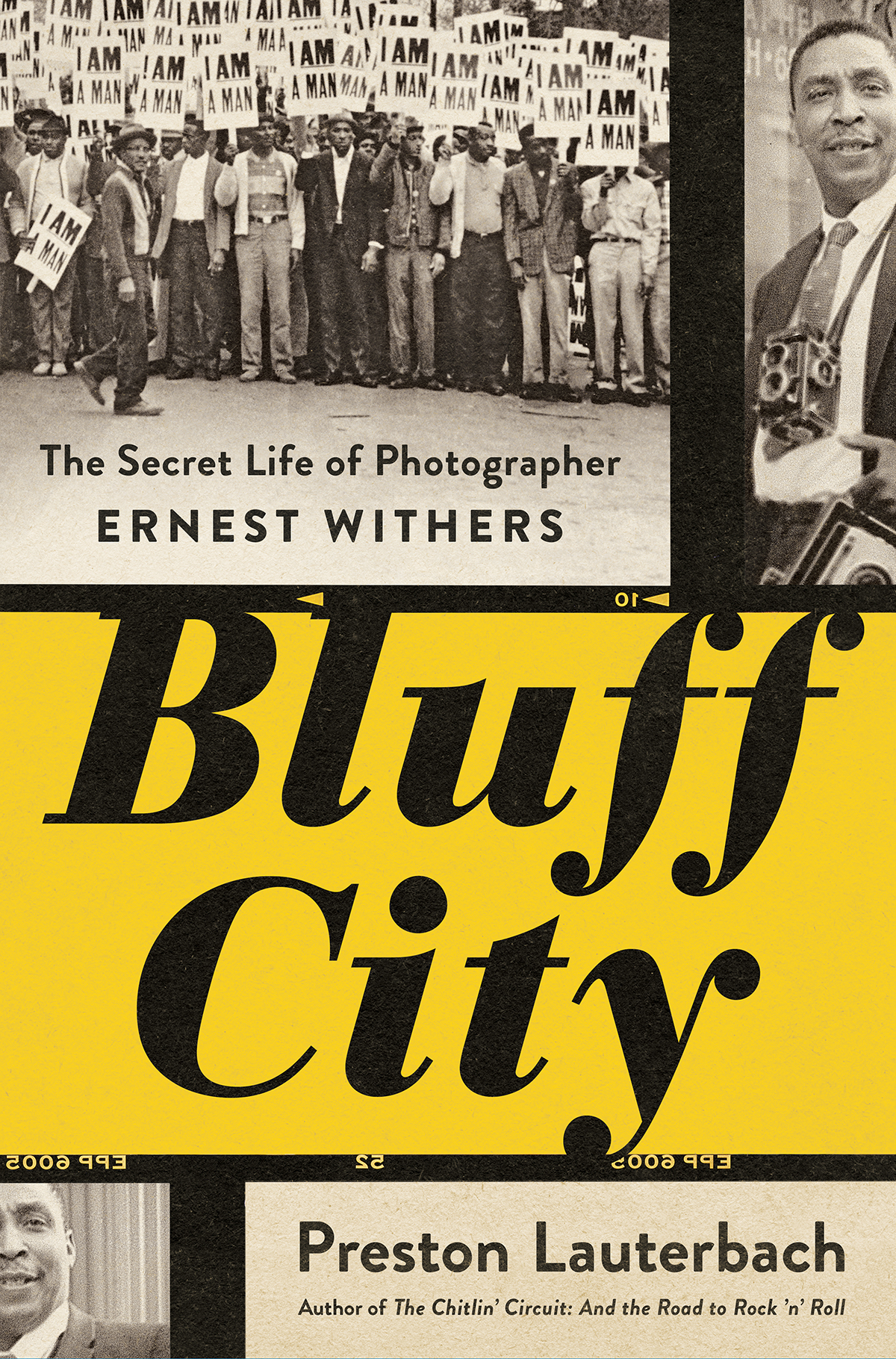

BLUFF CITY

The Secret Life of Photographer Ernest Withers

PRESTON LAUTERBACH

TO MAGGIE GRACE, SAX, AND OLIVIA

CONTENTS

THIS STORY CAME TO ME LIKE A DREAM. I FOUND MYSELF in the middle of it without meaning to.

In my early thirties, I showed up in Memphis. I had no roots there, yet I never felt more at home anyplace else.

The city felt strangely underhyped, despite its riches. I liked that. Memphis claims its the birthplace of the blues. Its definitely the home of the Souths first African-American millionaire, a freedman named Robert Church who made Beale Street into perhaps the most famous thoroughfare in the country. Journalist Ida B. Wells began her crusade on Beale, not long before a ruthlessly dominant political machine came to power in Memphis under Boss E. H. Crump. Plus, this laid-back, funky town is where Elvis began his career in 1954 and where Martin Luther King, Jr., was assassinated in 1968. The sound of soul music and the scent of barbecue smoke drift through the city uninterrupted. Imbibing this atmosphere became my favorite pastime. The past and present merged around crumbling buildings, neon signage, Kodachrome sky, weeds rising from the sidewalks, and surreal sights such as Isaac Hayes pushing his cart through the grocery store, his bald head still shining like Hot Buttered Soul, and Al Green preaching in a glorified country church before a mural of the apocalypse.

The pace of life moved at 99 percent humidity, only one percent faster than under water. The light took on a grainy quality. It might have been ragweed pollen, but there was definitely something in the air.

Memphis felt like the ancient Egyptian city of the dead, fallen with its grandeur apparent in ruin, the pharaohs and their secrets buried. How it all fit together, the King of Rock n Roll to Martin Luther King, Jr., I didnt know.

Memphis people didnt answer straight. My wife, a native, told me everyones lived in intimate oppression too long. The dynamic, she explained, is that African-American people need to survive, and whites need to not feel like complete dicks about racism. The result is a slow, roundabout way of being. Everyone has an ambling, rambling charm, a sense of automatic familiarity thats almost unnerving. The amount of conversation going on in public amazed me. Strangers chatted like friends. I grew up where you might get a hello in passing but were much more likely to get ignored. In Memphis, you couldnt buy a tube of toothpaste without hearing somebodys life story or telling your own. These people can really get you talking. I liked it, mostly. The eye contact and sense of connection struck me as perfectly genuine. Yet the longer I spent here, the stranger it felt. Because its built on high ground overlooking the Mississippi River, people call Memphis the Bluff City. The name seemed to have more than one meaning.

Without a nine-to-five, I followed my interest in the citys culture full time, researching the nightlife of the past. My explorations guided me to the citys famed thoroughfare, Beale Street.

The street I saw in 2004 bore no resemblance to the place where Elvis found inspiration in the summer of 1954, or where Dr. Kings final march met ruin in the spring of 68. Beale had been bulldozed in urban renewal and reborn as a tourist attraction la Bourbon Street. To see what had been, I relied entirely on the work of Ernest Withershed run a photography studio and one-man wire service on the street almost continually since the late 1940s. He left during the renewal period in the 70s and returned after its completion in the 80s.

His credo: Pictures Tell the Story.

Witherss images provided sharp detail about the vanished world of Beale and glowed with life.

The photographer had an uncanny ability to find not just breaking news but breaking history. You know his photos, even if you dont know the photographer.

In his pictures, Withers captured the emotional energy of the moment and a human essence of the people involvedthe jitters outside Central High in Little Rock, Arkansas, as one of the first black students to integrate the school dropped her books on her way in, and the cool of JFK campaigning, flashing the magic grin from within a sea of sign-waving protesters, his perfect hair a helmet against a hostile background. Withers also had a gift for gaining intimate access to powerhe made images of Elvis hanging out around African-American entertainers in 1956, and of Martin Luther King, Jr., sprawling across a bed wearing his white shirtsleeves in 1966. In this age of revolution, the world slowed in Witherss lens. He covered the 1960s as Mathew Brady covered the 1860s.

His work had gotten him beaten and arrested and threatened with death. His lens stared down cold-eyed killers and searched dark country back roads where outsiders like him had vanished forever. He navigated a hostile and mysterious country with audacity and sneaky wit. But in later interviews, he downplayed himself. I was there for a purpose and the purpose was to record the events that were taking place. It wasnt that I was doing it because I was any different. Its just that I was a news photographer and the news events were occurring.

He made the picture of Dr. King riding the first integrated city bus at the triumphant climax of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. When the photo ran front page across black America via the Chicago Defender in December 1956, an icon was born. The image still resonates, hanging in the National Portrait Gallery in Washington. Other Withers photos decorate the Smithsonian Museums of American History and African-American History, and the National Civil Rights Museum. And then we have his most enduring image, showing a group of Memphis sanitation workers gathered outside a church prior to their massive March 28, 1968, strike demonstration on Beale. They line up shoulder to shoulder, three or four deep, sidewalk to sidewalk, filling Witherss frame. They hold up picket signs, practically blocking the sky with the message I AM A MAN.

By the time I landed in Memphis, Withers had been recognized as a major photographer of the civil rights movement. His work had been shown in galleries and museums all over the country; hed delivered numerous college lectures, received an honorary doctorate, and published four books of his photos, covering music, civil rights, and Negro League baseball.

And like Al Green and Isaac Hayes, Withers was another fabulous individual casually arrayed in the city. Id run into him around town, and of course it was perfectly normal to say hello.

Withers dressed like a rumpled veteran journalist, in an old suit and often an American flag tie. He wore a brimless African-style hat called a kufi.

In summer 2005, after one of many stop-and-chats in the supermarket or the drugstore, I called Withers and asked if I could visit him. Id become deeply interested in the black nightclubs and musicians from the 1940s and 50s that hed so powerfully depicted. I wanted to get to know the people of this lost world. I didnt have a formal interview in mind. He said itd be all right.