Florence, A Delicate Case

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

The Marble Quilt

In Maremma: Life and a House in Southern Tuscany

(with Mark Mitchell)

Martin Bauman; or, A Sure Thing

The Page Turner

Arkansas

Italian Pleasures (with Mark Mitchell)

While England Sleeps

A Place I've Never Been

Equal Affections

The Lost Language of Cranes

Family Dancing

Florence,

A Delicate Case

David Leavitt

BLOOMSBURY

Copyright 2002 by David Leavitt

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the Publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Bloomsbury, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010

Published by Bloomsbury, New York and London

Distributed to the trade by Holtzbrinck Publishers

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Leavitt, David, 1961

Florence, a delicate case / David Leavitt.

p.cm. - (The writer and the city series ; 3)

eISBN: 978-1-59691-843-6

1. Florence (Italy)-Description and travel. 2. Florence (Italy)-Social life and customs. 3. Leavitt, David, 1961Homes and haunts-Italy-Florence. 4. Gay men-Italy-Florence-Biography. I. Title. II. Writer and the city ; 3

DG734.23.L43 2002

945'.51-dc21 2001056528

First U.S. Edition 2002

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Typeset by Hewer Text Ltd, Edinburgh

Printed by Clays Ltd, St Ives pic

Endpaper Map Copyright 2002 by Jeff Fisher

CONTENTS

For help of many kinds during the researching and writing of this book, I owe a debt of gratitude to Mark Roberts of the British Institute Library, Florence; Liz Calder, architect of this wonderful series; Colin Dickerman and Edward Faulkner at Bloomsbury; Jin Auh, Rose Gaete and Andrew Wylie at the Wylie Agency; James Lord; and most especially Edmund White, whose encouragement and support have mattered more to me over the years than he probably realizes.

This book could be dedicated to no one other than Mark Mitchell, the other half of the 'we' that narrates some of its pages. It was Mark who first brought us to Florence, in 1993; already he knew the city so well that for weeks I failed to learn its geography, so much easier was it just to follow him. He took me to see Benozzo Gozzoli's frescoes at the Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, and the building where Forster had slept. He introduced me to the ex-seminarian from Cosenza who liked to wear baroque liturgical vestments, and compelled me to try tripe. Later on, when I was writing, he brought to my attention all sorts of books I might otherwise not have looked at, read patiently through many drafts, and gave me the benefit of his great editorial skill. I am not exaggerating when I say that without him, this slim volume would never have seen the light of day.

I am nothing if not cultivated; or, at least, the world only expects culture from me. But, in my heart of hearts, I do not believe in culture except as an adjunct to life.

- John Addington Symonds,

in his memoirs

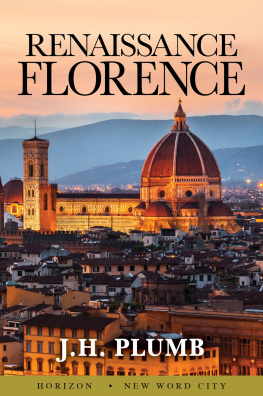

Florence has always been a popular destination for suicides. In the summer of 1993, when we first moved to the city, a girl jumped to her death from the top of the bell tower next to the Duomo. By the time we walked past, all that was left was a tennis shoe hanging from the scaffolding. La Nazione, Florence's newspaper, reported that she had been a foreigner, a tourist, which came as no surprise. A few months before, a vague acquaintance of ours, an actor whose career and marriage were both foundering, had flown in from Los Angeles, checked himself into the Hotel Porta Rossa, and promptly swallowed a bottle of antidepressants. He succeeded only in making himself violently ill, however, and after a few days in the hospital of Santa Maria Nuova, returned to California, to resume his down-at-heel life. In 1953, the American novelist John Home Burns, author of The Gallery, is said to have drunk himself to death at the bar of the Hotel Excelsior. (Ernest Hemingway, one of Burns's admirers, told Robert Manning, 'There was a fellow who wrote a fine book and then a stinking book about a prep school, and then he just blew himself up.') Old-world Florentine hotel rooms seem to be part of the allure, with their high ceilings, their fumaroles of dust, the door keys hanging from brass bells so heavy a pair of them could drag you to the bottom of the Arno.

I exaggerate here - which is easy to do in a city so fond of pomp, of ceremonies and regattas. We have a friend in Florence, a former seminarian (not Florentine; he comes from Cosenza, in the South), who every year at carnevale dresses in a set of heavily brocaded eighteenth-century liturgical vestments 'borrowed' from a church cabinet to which he, as church organist, has a key. Striding through the streets as if at the head of some religious procession, he exhibits all the baldanza, the grandiosity, of Cardinal Richelieu, or the grim reaper. In Florence death seems at once less fearsome and more glamorous than in other places, perhaps thanks to the superabundance of mortified Christs, many of them medieval and grimacing, with raw-looking wounds. On the newly restored cupola of the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore (or the Duomo, as it is more commonly known), Vasari's visions of heaven rise above a congested underworld in which unrepentant souls endure gruesome agonies. A long investigation into the case of the 'Monster of Florence', a serial killer who murdered sixteen people between 1968 and 1985, has come to the conclusion that the 'monster' was in the employ of a Satanic cult, the members of which includes some of the city's most powerful citizens, as well as agents of the Italian equivalent of the CIA. No wonder Hannibal Lecter decided to move here!

Of all those who have written about Florence, none caught its weird morbidity better than Walter Pater, who attributed to the Florentines of the fifteenth century 'a practical decision that to be preoccupied with the thought of death was in itself dignifying, and a note of high quality... How often, and in what various ways, had they seen life stricken down, in their streets and houses!' It is no coincidence that near the beginning of E.M. Forster's A Room with a View (1908), the most famous novel to be set in Florence, a murder is committed in broad daylight, in the Piazza della Signoria, and witnessed by Lucy Honeychurch, who, being English, promptly faints. Blood stains some photographs she has just purchased from Alinari, which George Emerson, having first rescued her, throws into the Arno. Yet the episode draws the pair together, and changes them both. 'For something extraordinary has happened,' George says. 'I must face it without getting muddled. It isn't exactly that a man has died.'

No, not exactly. But then again, what is 'it'? Exactly?

Almost a hundred years after A Room witha View, tourists still come to Florence seeking 'it'; and not just 'the barbarian hordes from the North' decried by Mary McCarthy, surging into town on buses from which they are disgorged like so many termites out of an exploded nest; also sober, cautious, well-read, intensely earnest visitors as avid as Lucy Honeychurch to enter 'the real Florence', to penetrate that elusive membrane that separates tourist experience from what might be called if finding the right words is difficult, it is because the concept is unreal - 'genuine' experience. Such visitors avoid at all costs restaurants with menus printed in English, even though these are often the better restaurants. Determined to steer clear of tourist-trap hotels, they stay in charming, if expensive, bed-and-breakfasts, and would never be seen carrying a phrase book. What they want from Florence is what George wants from Florence, what Pater wanted from Florence, what the young Forster wanted from Florence: that is, to satisfy in Florence some elusive idea of personal fulfillment with which the city's reputation has always been bound up - this despite the fact that so much about Florence promotes a contrary image.

Next page