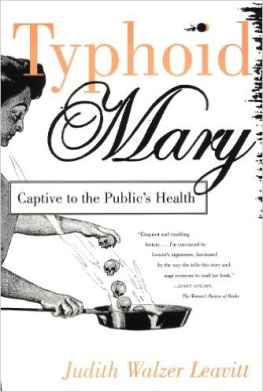

For Lewis

SONG OF SONGS 5:16

Contents

Illustrations

Water Filtration and Typhoid Fever Death Rates, 19001913

S. Josephine Baker, 1922

George Soper, 1915

Mary Mallon in Willard Parker Hospital, 1909

Close-up of Mary Mallon in Willard Parker Hospital, 1909

Typhoid Mary, drawing, New York American , June 20, 1909

Typhoid Mary, article, New York American , June 20, 1909

Mary Mallon, portrait with cartoons, 1909

Mary Mallon, drawing, 1933

Mary Mallon at stove, drawing, 1935

North Brother Island Plot Plan, 1943

View from North Brother Island

Excerpt from Mary Mallon letter, 1909

Mary Mallons tombstone

Mary Mallon, Innocent Killer, drawing, 1957

Mary Mallon in kitchen, drawing, 1966

Mary Mallon advances on George Soper, drawing, 1970

Police arrest Mary Mallon, drawing, 1970

Mary Mallon followed by health officers, drawing, 1970

Typhoid Mary, drawing, 1979

Mary Mallon, drawing, 1984

Acknowledgments

I T IS ALWAYS A GREAT PLEASURE, UPON

completing a project such as this one, to remember all the people whose efforts helped make it possible and to have an opportunity to thank them publicly. In this case there were many, and their efforts mighty.

I begin with the students in my course, The Development of Public Health in America, at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Since 1976, undergraduate and graduate students alike have demonstrated their fascination with Mary Mallon and the ways they could use her story to illuminate continuing issues in the field. I cannot name all of the students whose excitement with this subject finally ignited my own to the point that I began this project, but I understand my debt to them. Like all professors, I learn much from my students.

I would like to thank many graduate students in the history of medicine at the University of Wisconsin for the role they played, first in the classroom, and continuing beyond, in helping to shape my ideas and to sharpen my thinking. To Jon Harkness I owe a special thanks. Over the years, Rima Apple, Bob Bartz, Beth Black, Charlotte Borst, Marc Dawson, Diane Edwards, Eve Fine, Liz Hachten, Patty Harris, Judith A. Houck, Mary V. H. Jones, Susan Eyrich Lederer, Lian Partlow, Leslie Reagan, David Sandmire, Lisa Saywell, Rennie Schoepflin, Susan L. Smith, Diana R. Springall, Karen Walloch, John Harley Warner, and Tom Wolfe have pushed me even as I tried to push them. I am grateful to them all.

My colleagues at the University of Wisconsin have been equally important in helping me develop and continuing to challenge my ideas about what meanings we can derive from Mary Mallons experiences. I would like to thank, in the history of medicine, Thomas Broman, Harold J. Cook, Vanessa Northington Gamble, and Ronald L. Numbers for putting up with this project and, more significant, for putting up with me as I obsessed about it. I would also like to thank all the graduate students and fellow faculty in the history of science and in womens studies for their considerable interest in this project.

My family, of course, has had to put up with more than anyone else. I am ever grateful to my children, Sarah A. Leavitt and David I. Leavitt, who, now adults, offer a special blend of intellectual and familial encouragement. Both of them provided practical help to this specific project as well as general goodwill about difficult schedules and delayed activities. My mother, Sally H. Walzer, who moved to Madison in the middle of this undertaking, has been ever-eager and supportive of my work on Mary Mallon as she has been of each of my career steps since I was too young to notice. Without her encouragement, and that of my father, Joseph P. Walzer, which I continue to feel through her, I would not be in a position to write this book. To Lewis A. Leavitt I owe more than can ever be written on the page. For his loving support over thirty years, and in anticipation of many more ahead, I dedicate this book.

This project benefited greatly from the research assistance of a number of people. I would like to thank Dawn Corley, Irving Ishado, Sarah A. Leavitt, Jennifer Munger, Lian Partlow, and Sarah Pfatteicher, all of whom were creative and resourcefuland persistentin tracking down sources. For special contributions and consultations, I am happy to acknowledge the help of Nina Ackerberg, Peter Ackerberg, John Q. Barrett, Joan Jacobs Brumberg, Ann Carmichael, Bob Conlin, Gerard Fergerson, Vanessa Northington Gamble, Bert Hansen, Dirk Hartog, Greg Higby, Saul Jarcho, Robert J. T. Joy, David I. Leavitt, Barron H. Lerner, Gerda Lerner, Stephanie Mathy, John Parascondola, Sarah Potts, Carolyn Shapiro, Robert Skloot, and Rebecca Walzer. These people were willing to put aside their own work to offer help at very important moments in the project, and I am extremely grateful to them all.

I am grateful for the responses of many people to my Authors Query in the New York Times Sunday Book Review section and the Irish Echo . These letters not only answered many of my questions, they also provided the comfort of knowing there were people out there who might be interested in reading this book.

I am in great debt to my colleagues who took the time to read a draft of the complete manuscript and offer detailed and informed opinions about what they read. I want to thank Thomas D. Brock, Susan Stanford Friedman, Linda Gordon, R. David Myers, and Ronald L. Numbers. While I know I did not answer all their concerns, I benefited from their insights, and I tried to do justice to their comments. I know some of their collective wisdom is reflected in the pages that follow, but these wonderful scholars are in no way responsible for the mistakes and shortcomings that remain.

I am happy to acknowledge the financial support that allowed this project to come to fruition. Foremost, I am grateful to the National Endowment for the Humanities, and to project officer Daniel Jones, for generous grant support, and to the University of Wisconsin Foundation for its matching grant. The University of Wisconsin, Madison, sabbatical program provided one semester free of teaching duties. The Institute for Research in the Humanities at the University made a home for me for one semester, and I benefited from the experience there of trying out my ideas in an interdisciplinary group. My tenure as Evjue-Bascom Professor of Womens Studies (19901995) provided added support for this project. Without all of this help, this book would not have become a reality.

I especially want to thank three people whom I have come to know quite recently. They have made it possible for me to have access to materials otherwise hidden, and their cooperation and enthusiasm for my project have been of ultimate importance. I am ever grateful to John S. Marr, M.D., M.P.H., now of the State Department of Health in New York; Ida Peters Hoffman, now retired from the City Health Department; and Emma Rose Sherman, also retired from her work first in bacteriology and then in education for the City of New York. These people were generous with their time and their knowledge; they opened their homes and their archives to me and shared their research, experiences, and memories. Only scholars and writers who have received similar help in their research from such personal and open communications can understand my debt and my gratitude to these three people. I only hope they get some pleasure out of the completed project.

Parts of are reprinted and used here with permission: Typhoid Mary Strikes Back: Bacteriological Theory and Practice in Early Twentieth-Century Public Health, Isis 83 (1992): 60829; Gendered Expectations: Women and Early Twentieth-Century Public Health, in U.S. History as Womens History: New Feminist Essays , ed. Linda K. Kerber, Alice Kessler-Harris, and Kathryn Kish Sklar (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995), pp. 14769.

Next page