Also by RICHARD ADLER AND FROM MCFARLAND

Victor Vaughan: A Biography of the Pioneering Bacteriologist, 18511929 (2015)

Cholera in Detroit: A History (2013)

Mack, McGraw and the 1913 Baseball Season (2008)

Typhoid Fever

A History

Richard Adler and Elise Mara

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-2209-5

2016 Richard Adler and Elise Mara. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

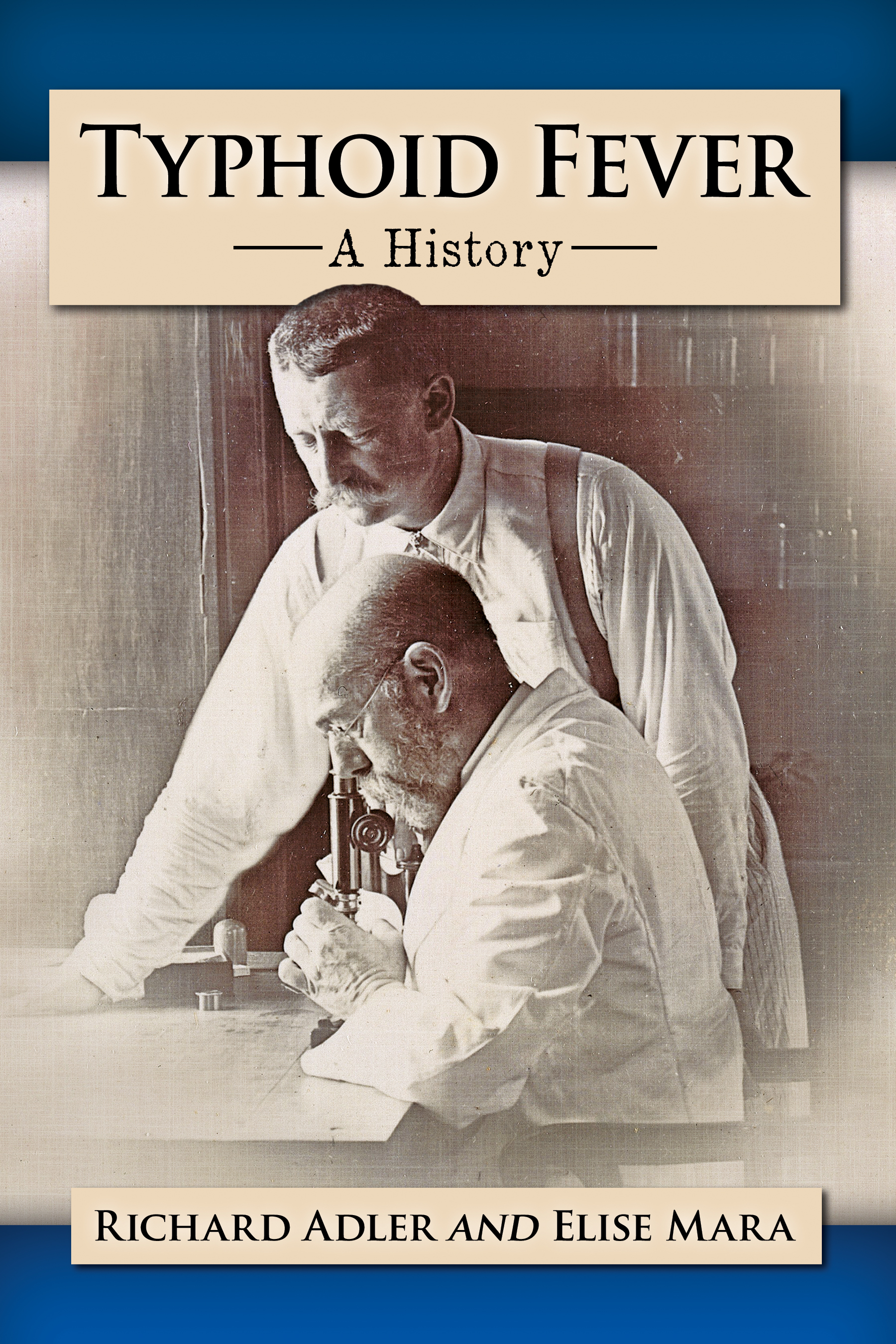

Front cover: Richard Pfeiffer (standing) and Robert Koch (image courtesy Wellcome Library, London)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the following individuals for their support, monetarily and otherwise, in the writing of this book: John Cristiano and the Office of Sponsored Research at the University of MichiganDearborn; Doug Atkins of the National Institutes of Health, National Library of Medicine, for the extra, extra (intentionally repeated) effort he carried out in tracing copyrights; Rose Adler in helping prepare images; Jeff and Sue Mara for generally being supportive and encouraging one of us (E.M.) to continue working on this book; Sally Adler for her supportive help; and Rodney Foster, RN, who provided an appreciation and interest in epidemiology and for the human stories in public health.

Preface

There is a fascination, a dramatic interest, in working out, even in imagination, the dark and devious paths and bypaths along which the microscopic parasites that afflict the human race travel to their appointed victims. Only the epidemiologist realizes the full meaning of the phrase, the pestilence that walketh in darkness.George Chandler Whipple

Typhoid fever is a disease with a muddled past. It is likely that itas well as other gastrointestinal illnesseshas been with us since antiquity. However, tracking it through the history of civilization is complicated by the fact that until the 19th century it remained difficult to reliably distinguish this illness from other fevers that had similar characteristics. Lacking the distinctive symptomology of infectious diseases such as smallpox or syphilis as it was first described in the 16th century, typhoid was frequently confused with typhus or malaria (indeed, typho-malaria was considered a specific illness well into the 19th century) in the years before advances in pathology and germ theory would shed light on the characteristics and etiology of the disease. This era of loose definitions survives even in the name itself: typhoid, the oid referring to an organism believed distinct from others for which it may have been mistaken. Generally applied, the term was an adjective which literally meant resembling typhus, the designation of typhus referring to the unpleasant odors emanating from putrefying material that were believed to be associated with, if not the direct cause of, disease. Other examples include the original applications of names which evolved into influenza or malaria.

It is perhaps understandable that ancient physicians and historians had difficulty differentiating between the major fevers: malaria, typhus and typhoid. Each of them exhibits very similar symptoms. Any attempt by modern historians to identify or diagnose such illnesses produces the challenge of not only dealing with what were largely observationsbodies warm to the touch or undefined blisters or rashesbut also in translating ancient terminology. Typhus and typhoid fever were particularly difficult to differentiate, as each could be characterized by a high, prolonged fever, the level of which could not be determined by the ancients, as well as headache, rash and abdominal pain. At least malaria, which unquestionably existed within the swamps and standing waters or any other place infested by mosquitoes, produced an intermittent or repetitive fever interspersed with chillsmost of the time. Malaria was likely among the tertian (two-day interval) or quartan (three-day interval) fevers described by Hippocrates on this basis (see Chapter 2). The Roman historian and physician Aulus Cornelius Celsus (ca. 25 BCE50 CE) provided almost a modern textbook description of malaria in his surviving text De Medicina:

But quartans are simpler. The fevers begin with shivering, then a heat erupts, and then, the fever having ended, the next two days are free of it. On the fourth day it returns.

However, tertian fevers surely have two types. The one type beginning and ending in the same manner as a quartan, the other with only this difference; that it allows one day to be free of it, and returns on the third. The other type is far more insidious, for it always returns on the third day, and out of forty-eight hours, thirty-six of them (although sometimes less or more) are occupied by the paroxysm. Neither does it completely halt during remission, but only takes a lighter course. This type most physicians call semitertian (intermittent with characteristics of both daily and tertian).

Celsus was therefore able to differentiate the (intermittent) fever characteristic of malaria with that of typhoid or typhus.

It would require the scientific observations of physicians in both Europe and the United States during the middle and late 19th century to unravel the puzzle of what typhoid fever actually was and, equally important in the understanding of its etiology, what it was not. As was the situation with several of the significant gastrointestinal illnesses intensively studied during that century, such as cholera or dysentery, the isolation and identification of the agent came decades after its method of transmissionthrough sewage-contaminated waterwas determined. One can make the argument that understanding the method of transmission and identifying the agent led directly to the establishment of public health departments in an increasing number of cities, both in Europe and the United States. The difficulty in isolating and identifying the typhoid bacillus, now placed within the genus Salmonella, led to the use of a surrogate marker, once known as Bacterium coli (now Escherichia coli), to identify water supplies contaminated with sewage. Generations of microbiology students have since been challenged with learning and understanding the methodology of numerous biochemical tests used in differentiating common soil microorganisms from those which signify potential problems.

So what, one may wonder, made it so difficult to discover the underlying cause of the disease? The challenge in identifying the actual etiological agent was understandable only in the context of 19th-century bacteriology. The typhoid agent is not a virus. In fact, it is not even a particularly unusual bacterium. Salmonella will grow on most of the standard laboratory media, whether in those of more modern times or in the extant media of the 19th century. Even Victor Vaughan, dean of the University of Michigan Medical School between 1891 and 1921 and among the most important of the bacteriologists during that era, acknowledged as much. The problem, of course, required first the observation and isolation of the organism from the victim, and then linking the isolate with a specific disease. A few similar examples linking an agent with an infectious disease could be found through much of the latter half of the 19th century. Anthrax is one such case in point. But it was the institution of what became known as Kochs Postulates during the 1880s which provided a working guide to physicians attempting to identify an etiological agent. The eponymously named postulates, generally attributed to the German physician Robert Koch while often ignoring the earlier models on which the postulates were based, are relatively simple in their concept: (1) the agent should be present in all cases of the disease, while (usually) not present in the absence of the disease; (2) the agent should be grown in pure culture and following inoculation into a test animal; (3) should produce the same disease; and finally, (4) the same agent should be reisolated from the test animal. It was not until the latter years of that century that this could all be put in place for the more common bacterial diseases. But even after these concepts had been applied by Koch and his associates and the concepts had gained widespread acceptance, certain bacterial diseases failed to fall neatly within the principles of the postulates. For example, neither the comma bacillus of cholera nor Eberths bacillus, as the typhoid agent was sometimes termed, produced their respective diseases in common laboratory animals. As a result, even Vaughan remained skeptical for a time of the alleged role played by Eberths bacillus as the etiological agent of typhoid.

Next page