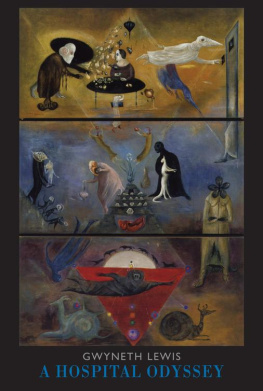

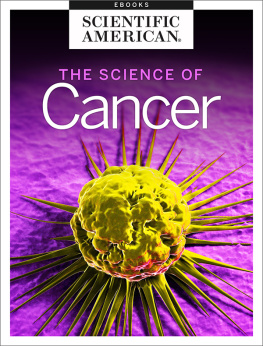

is an outrageously imaginative voyage through illness and healing. Drawing on the most recent biomedical research into stem cells and cancer, the poem is a journey through the bodys inner space and the strange habitats created by disease, including the chimeras people see when theyre unwell. Maris, whose husband, Hardy, has been diagnosed with cancer, is separated from him. Her mythical journey leads though a surreal landscape, peopled by true and false physicians, god-celebrities, rabid statues, diseases hunting healthy bodies and a microbes holding their annual ball. The Otherworld is located in the hospitals basement. In her desperate search Maris meets and converses with Aneurin Bevan, founder of the NHS.

Adapted from Anon, 15th century Dear God Please bring my husband back home EBM (Prayer book, St Bartholomews Hospital chapel, London)

Ill kill you if you die on me now, hissed Maris. Her husband Hardy, barely alive, winced. His trolleys prow parted Emergencys human waves, passed luckier patients in curtained caves and came to rest in a corridor. She looked, concerned, at his grey-tinged skin.

Shining with fever, his eyes were stars speeding away from her. A vein pulsed in his throat. She tried again to reach him but hed set sail without her on an internal sea and, for all she clutched at the flimsy rail of his cot, hed already drifted away, caught by the current, left her on a quay alone. She fired emergency flares of love but it was far too late to call him back. He was deaf to her, so she watched him, utterly desolate as the man shed married sank from sight over pains horizon. He was her compass in fog, her favourite mountain road, her eternity ring of precious stones worth everything, the load shed willingly carry.

Hardy groaned. Im off to the Pharmacy, she said, stroking his cheek. He closed his eyes, too busy with dying to raise his head. She found herself saying a silent goodbye to her husband. She was terrified hed be changed for ever, against her will, by illness. Suddenly she turned a corner into the concourse, then stood stock still in wonder.

Now I want you to hear a sound-track: a sci-fi fanfare, the kind when a novice traveller sees her first spaceship, takes in with awe its unimagined scale and grandeur, the hum of its engines, the sheer power of sophisticated alien culture. Maris stood and all around her people thronged. She was enthralled by the infinite corridors that converged like a print by Escher. Market stalls traded toys and small furry animals which visitors carried to the unwell. Long escalators ran in spurs, moving the healthy as if they were cells in a greater body, seeking a cure for themselves or others. It was a fair: balloons drifted up from the foyer.

Hawkers were pushing dubious pills. Maris watched a group of tumblers Performing: The Body. Flexing impressive muscles, they made her forget her husbands ills for a moment. Above it all hung a magnificent chandelier throwing spangles like the glitter ball in a disco. Strung on the finest gossamer, the ever-replenished ornament of tears was the hospitals primary source of light. The diamants fell like dew on those who gazed up at the dazzling sight.

Distresses formed themselves in new constellations of glittering sorrow before they ripened like fruit and fell. Maris noticed box-lit X-rays under a sign: Diagnosis Wall. Doctors peered at MRI scans, each one looking intently at portraits of internal cavities. They issued their verdicts. Maris heard them whispering the simple litany: Normal. Not normal. Then, unperturbed, theyd stamp a Latin medical word on a file for consultants.

Phials of blood were being analysed next door. A robot shook them, thick as mud, then sampled each glass, a sommelier guessing a vintage. Mariss eye was caught by one bottle, which bore the name of her husband: Hardy. It was ruby red, an impossible scarlet that caused her alarm the moment she saw it. Sick with dread, she watched the gourmet as it tasted, swilled the wine round its specialist mouth then spat out the taste of her husbands health. It hummed and had, its innards whirred and said it detected a soupon of anaemia then worse.

It printed the verdict: CANCER. Maris was stunned. This was a story that happened to others, not to Hardy and her. Then she was pierced through with pity for him, brave man, whod hidden his terror of this, the most feared saboteur of all. Stop reading. If your partners near I want you to put this poem down, surprise them at the morning paper.

Nuzzle their neck. When they ask, Whats wrong? say, Nothing, but hold them close, while you can. Soon Maris was crying huge snotty sobs, responding with shock and disbelief to the verdict, how shed soon be robbed of her husband by a cellular thief, a fifth columnist. Then came grief and Maris howled, leant into an alcove and let heartache have its way with her. Yes, loss is the shadow of love but its a scandal that bodies must die, dont you think? My dear, its not done to cry like this in public, a pert voice said. Come to my office.

We hold a licence for weeping there. Lucky I spotted you. Theres a particular brilliance to your sobbing. The woman was a no-nonsense bureaucrat. Maris blew her nose on a proffered tissue. Quite a threnody you produced.

It wasnt a show. I think you may be a natural weepie. A Wednesdays child? Theres pots of money to be made from blubbing, if its not real. Professional weepers sipped sweetened tea and bawled. Not everybody wants to feel their lives and we find insincerity does just as well. You have ability, and could supply a valued service if you stayed with us.

We work in shifts, on commission. Men are generous. Some women, we find, give us short shrift for pretending, like them. Theyre only miffed because weve made it professional. I dont mind some clients on the side if youre discreet. On the whole, its better than cleaning.

I think youre sad. The people who pay you must be mad. I need the Pharmacy. But the woman wailed which raised a chorus of put-on woe, an ululation which so assailed Mariss ears she just had to go. Lost, she wandered to and fro looking for signs. She asked the way from a porter who mumbled lazily and waved in a certain direction and then sashayed away with his wheelchair.

Maris was still nave in the ways of this hospital so, when a nave opened in front of her, she wasnt surprised but thought, Ill sit in this pew for a while to compose myself. A musky rose adorned the altar, its scent narcotic. Ill just close my eyes. Her dreams were febrile, a million tendrils had crossed the floor and were probing, curious to know how she tasted. Subtle suckers entered her pores, were thriving, somehow, on her sorrow. Branches, engorged now, thick as her torso, were tying her down.