The Red Shingled House

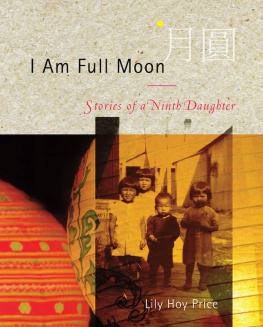

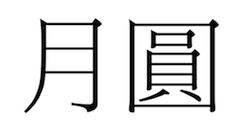

I was born in 1930, the ninth girl in a family of twelve children. My mother gave us our Chinese names and my father gave us our English names. I was named Lily, and my Chinese name means Full Moon. We lived in a village in a quiet valley at the confluence of the Quesnel and Fraser Rivers in the heart of Cariboo country in British Columbia. Today Quesnel describes itself as a city, but it was home to only three hundred people when I was born. Our community was at the northern end of a narrow, winding and dusty highway of dirt and gravel, eight hundred kilometres north of Vancouver. Miners and prospectors had eked out this route as they followed the meandering Fraser River during the Cariboo gold rush of the nineteenth century. I think of the Quesnel of my childhood as a Brigadoon, a village hidden in time, yet to be discovered.

My family lived in a small, shingled house until I was four. The house was painted a dark red and had a black roof. It was lodged between a corrugated tin garage and a log barn on Barlow Avenue, a dirt and gravel street edged on either side by wooden sidewalks. A gated wire fence enclosed the front lawn, bordered by lilac bushes, and a cemented walkway led up to the porch entrance.

The main floor had a kitchen, a master bedroom with bath, and a living room. The kitchen contained a cast-iron stove, a wood box, a small counter, a round table and a ceramic sink with a cold-water tap. A door opened to a large backyard.

We had running water and electricity as far back as I can remember. However, my sister Lona reminded me that we didnt always have tap water. We had a well with a bucket just outside the back kitchen door. She helped my mother haul water to fill the kettle and the stoves hot water tank. My sister Rose remembers the well as a cool place to set a bowl of jelly. My sisters couldnt recall when tap water replaced the well, but they said we always had electricity.

The boys shared the master bedroom with my parents. It was a busy thoroughfare as we trundled in and out of the room to use the only bathroom in the house. The room contained a flush toilet, a basin, an English style tub, and a barrel heater. Once a week three or four of us girls shared a bath. Ma-mah heated a drum of water on the barrel stove. When the water was steamy hot, she poured it into the bathtub and cooled it by turning on the cold-water tap.

At bath time, the bathroom was cosy-warm and smelled of firewood and steamthe way bonfires and wet bathing suits sometimes smell. We stripped and left our dirty clothes on the floor and stepped into the soothing, lukewarm water. Once in the tub we splashed about, wet the floor and soaped ourselves with a bar of soap. We giggled and laughed, enjoying the moment until Ma-mah said, Okay, let me wash your hair. We hated having our hair washed and protested.

Not me first, Ma-mah, not me first!

My hair isnt dirty!

Do Lily first!

No, do Mooney!

Ma-mah said, Close your eyes. With a bar of Sunlight soap, she lathered our hair and scrubbed our scalps as we yelped and howled.

Not so hard!

Ouch, that hurts!

I got soap in my eyes!

Ma-mah poured clean warm water over our heads to give them a rinse, then a quick rub with a towel. She let us play in the murky warm water even though a dark line rimmed the tub, and the film of soap suds floated and clung to us like drowned dandelion seeds. Afterwards, we stood nude by the stove, soaking up the heat and drying ourselves. We dared one another to stick out our tummies as close to the stove as possible without getting burned. The inevitable happened when Star ran screaming and crying with a scorched tummy to Ma-mah. Our daredevil game came to an abrupt end.

On chilly evenings we gathered around a small, oblong stove in the living room. Hidden behind its north wall, a narrow staircase led to an attic bedroom. We nine girls shared this attic room under low, slanted ceiling. The room had a bare wooden floor and one window, and it was large enough for three beds and a large crib. The three youngest girls slept sideways in one bed. The others occupied the other beds, except for Rose, who slept in the crib because her hands were covered with eczema that caused her endless hours of discomfort.

The attic was a noisy, crowded room without closets, dressers or drawers. Dishevelled clothes and bedding hung askew. The smell of urine permeated the thin, lumpy mattresses. A sixty-watt bulb, screwed into a ceiling socket, illuminated the chaotic scene.

In this jungle of a bedroom, I experienced my first Christmas. Our family didnt celebrate Christmas in the early years, but as a small child, I vaguely understood it meant presents, Santa Claus, and a decorated tree. My older sisters talked about it and repeated stories from school. They always told us when it was Christmas Day.

On the Christmas Day when I was three years old, I woke up shivering in the icy bedroom. My two siblings had rolled themselves into one big ball with the only feather comforter we shared, leaving me with a flimsy flannelette sheet. I pulled and yanked at the comforter, applying my feet to break apart the sleeping twosome. As I struggled to free the cover, I happened to look up. To my surprise, I focused on a sight that made my jaw drop. I released the bedding and jolted upright. Opposite the foot of my bed, slept my two oldest sisters, Avaline and May, in a white, curlicue wrought-iron bed. Little gift-wrapped packages hung from the curlicues intertwined with strips of red and green crepe paper.

Look! I shouted.

Eight tousled black heads, eyes like raccoons, peered out from under the covers. Their eyes followed my pointing finger, and just like me, they jolted upright in disbelief.

Where did they come from?

Who are they for?

Did Santa come and leave us a present?

Avaline surveyed the scene with a chuckle. She was our eldest sister with the sweetest disposition, and we looked up to her as our second mother. Whenever Ma-mah needed help, she took care of us. And when Pa-pah came close to a nervous breakdown, she quit school in Grade Eight to help him in the family store.

Unable to contain her secret, Avaline swung her feet into a pair of cloth slippers, slipped on a black and red housecoat, spread her arms and exclaimed, Merry Christmas, everyone! She tapped one of the packages, which set it in motion, and said, This is just a little something for each of you and Benny. Baby Jacks too young for a present.

A Christmas present? It was something wed never had. I tore open my gift and yelped when I saw a box of Cracker Jack popcorn with a toy inside. Im going to show Ma-mah, I said, and scampered down the rickety stairs. The others followed, gesturing toward their boxes of popcorn, handkerchiefs, hair clips and ribbons, calling, Ma-mah, Pa-pah, see what we got!

What is it? Ma-mah asked, as we burst into their bedroom.

We got a Christmas present! Avaline gave us a Christmas present! See?

A Christmas present? said Ma-mah, glancing at Pa-pah. They laughed and said how lucky we were, and then wished us a Merry Christmas.

Years later Avaline confessed what she had done. I never paid for the items I gave to you kids, she told us. I just took them from the store.

I remember that the backyard was our playing field. Chickens wandered around it freely. Since we didnt have toys, apart from a wagon, we created our own imaginative fun. We climbed the mountainous woodpiles, splashed in a large galvanized rain barrel, built playhouses from cornflakes cartons. A deserted farm wagon became the territory of Cowboys and Indians. One day as we whooped and hollered on the wagons deck, four-year-old Mooney accidentally fell and broke her arm. For the next few days, Lona, who was seven, and Star, who was five, sympathetically pushed her around in a creaky, lopsided baby buggy.