Contents

Guide

In loving memory of my adored mother, Nina, and my little brother and sister, Bela and Berta, all of whom were murdered in the gas chambers of Auschwitz-Birkenau. This book is also dedicated to the many members of my extended family who were killed, and to all those who have no one to remember them.

Contents

For the Jewish people, the Holocaust was a personal tragedy. By the end of the Second World War, one-third of European Jewry had perished at the hands of the Nazis. Six million innocent Jewish men, women and children murdered for no reason other than the religion they were born into. A great pillar of smoke covered all of Europe; the shadow of which remains with us still today.

Yet the Holocaust was also a universal human tragedy. It was the greatest crime of man against man, during which humanity showed itself capable of incomparable inhumanity on an incomprehensible scale. Names were replaced by numbers, tattooed on forearms, as a permanent reminder of the depths to which humankind can sink and the evil it can impart on a fellow human being.

The late Chief Rabbi, Lord Sacks, spoke about the profound difference between history and memory. History, he taught, is his story an event that happened sometime else to someone else. Memory is my story something that happened to me and is part of who I am. History is information. Memory, by contrast, is about identity History is about the past as past. Memory is about the past as present.

It is the Holocaust survivors who help us transform history into memory by their ability to humanise the inhumane. It is them and their words that make the past present.

Throughout my life, I consider it a singular privilege to have met so many survivors. As Patron of the Holocaust Memorial Day Trust, I have witnessed, and been greatly moved by, their harrowing testimony. I have drawn personal inspiration from the many Righteous among the Nations, who, like my dear grandmother, Princess Alice of Greece, put their own lives at immense risk to save Jewish men, women and children from certain death. I have seen the impact survivors words and their sheer presence have had on others, in schools, communities and organisations across our country and around the world.

One such occasion was in 2015 when my wife and I were particularly honoured to light six remembrance candles as part of the National Holocaust Memorial Day Ceremony in London. For the lighting of each candle, we were joined by a survivor who, like many others, had rebuilt their lives in the United Kingdom after the Second World War and contributed enormously to the fabric of our nation. One of the survivors was Lily Ebert B.E.M.

The joint lighting of the candles was a recognition that the responsibility of memory is slowly but surely passing from the survivors to our generation, and to future generations not yet born. It symbolised the need for us to be fearless in confronting falsehoods and resolute in resisting words and acts of violence. It called on us to recommit ourselves to the beliefs of tolerance and respect and the central idea, set out in the Hebrew Bible, of btzelem elokim, that we are all, irrespective of race, colour, class or creed, created in the image of God.

These lessons, important then, remain vital now especially when the events of the Holocaust are sometimes distorted, diminished, or denied, the testimony of victims and witnesses is invaluable and essential. This is what Lily, together with the other Holocaust survivors, understands only too well.

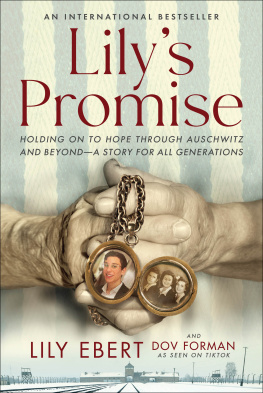

In co-authoring this book with her great grandson, Dov Forman, Lily has lit her own candle, and recognised the urgent necessity of passing both its light and the responsibility of remembrance between the generations. This is a task Dov has shown himself more than capable of carrying forward. Through his engaging and effective use of social media, Dov has demonstrated a determination to share his great grandmothers story with a global audience. In being an enthusiastic partner in this work, Lily is once again showing her passion to use every avenue available to ensure that some good might come from the horrendous losses she suffered and the unspeakable evil she overcame.

Lilys story is as profoundly moving as she is inspirational. It is for these reasons, among others, that I was humbled to be asked to contribute a foreword. She and her story are a beacon of light in the darkness; a symbol of hope amongst the despair.

In the depths of Auschwitz, Lily made herself a promise that if she survived, she would dedicate the rest of her life to ensuring the world knew what happened during the Holocaust. This book, which so powerfully captures her testimony, represents the fulfilment of that promise and the culmination of a lifetime of service to the human conscience. We would all do well to make Lilys history our memory.

Lets do something, Dov!

My great-grandmother is restless. Ninety-six years old, Lilys used to spending her days in schools, talking to children about her experiences in Auschwitz, or campaigning at public events. She hates being stuck in her flat alone.

Pandemic lockdown rules have eased at lastat least for the time being. After too many shouted conversations through a window while we stood in the garden, my family can finally spend Sabbath with Lily again, as we always used to.

Lets do something, Dov! says Lily.

Its Friday night, and were gathered in our bubble round the table. Were all so happy to be with each other again, lighting the Shabbat candles together, blessing the bread. Such a special evening. Lilys full of energy.

But I can see how much she misses her old life. Shes always thrived on meeting new people. As a living witness, Lily cherishes her role in Holocaust education. Its not easy, but shes determined to make a difference. She knows how much it means to people to hear her story from her own lips, how meeting her face to face can change the way someone sees the past and also the future.

Dont worry, Safta! We all call her Safta because thats what Mums always called her. Its Hebrew for Grandma. Ill think of something.

What can I do?

Schools and museums and universities have reopened, but nobody knows when public events might be possible again. It could be years. How many Holocaust survivors will still be alive by then? The Covid crisis has brought home a very painful truth: tough as she is, immortal as she seems, however much I love her, my great-grandma cant live forever.

Lily is amazingly adventurous. Shes always curious about new things. A few years ago she sat on a sofa in the middle of Liverpool Street station and invited commuters to sit down and talk to her about the Holocaust. Last year we started a Twitter feed together. I tweeted a few times about Lilys talks for Holocaust Memorial Day in January.

Now Im thinking more seriously about using social media to introduce Safta and her story to new audiences. Shes taught me so much. Everyone who meets her adores her. And if ever there was a time to spread her message of tolerance, it feels like now.

Maybe we can do another tweet? I suggest.

Or another school visit? she replies eagerly.

Two weeks ago I organized her first Zoom appearance. She shared her testimony with my history teacher and answered his questions carefully. Shed never heard of Zoom before, but took to it like a pro. I was so proud. I contacted a journalist on