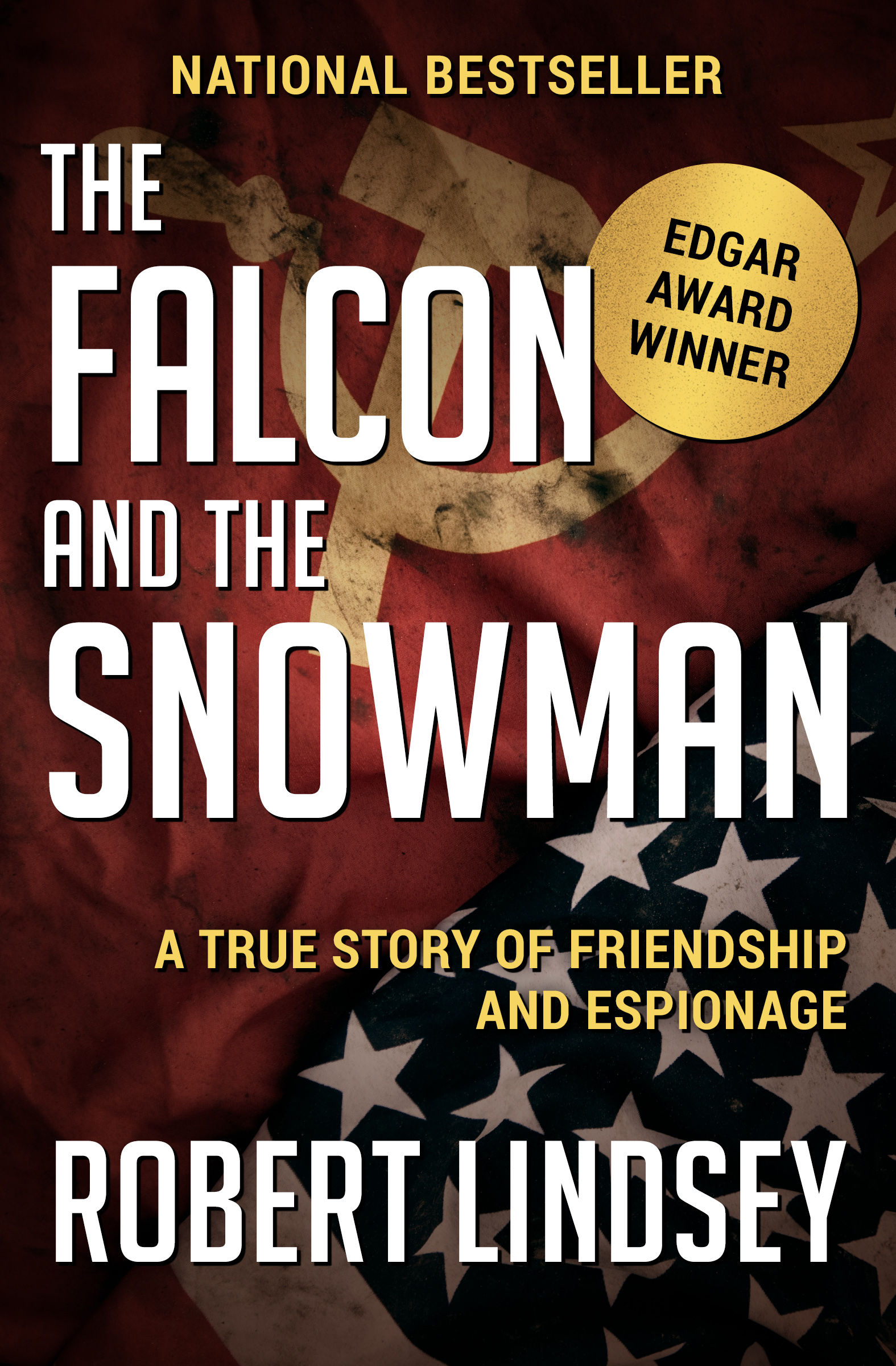

The Falcon and the Snowman

A True Story of Friendship and Espionage

Robert Lindsey

T O S ANDRA,

MY STAFF OF LIFE

WHAT FOLLOWS IS A TRUE STORY. THE NAMES OF CERTAIN CHARACTERS HAVE BEEN CHANGED IN ORDER TO PROTECT THEIR PRIVACY .

A halo of smog hung over Mexico City on the morning of January 6, 1977, obscuring the mountains beyond the city with a brown membrane of moist soot. Christmas decorations, remnants of Posada, the citys most festive celebration, still clung to many of the buildings on the Paseo de la Reforma, the broad boulevard that sweeps proudly from the Old City to Chapultepec Park, a Latin American Champs-Elyses.

It was the Day of the Three Kings, and, as was the tradition, children throughout the capital of Mexico were opening their Christmas packages. Under an elm tree along Reforma, an organ-grinder cranked out the repetitious strains of a Strauss waltz, entertaining tourists beside the statue of Cuahutemoc, the last of the Aztec emperors, while his assistant, a small boy, scurried about, cap outstretched, soliciting coins.

Behind the glittering window walls of the office towers that loomed over the tree-lined boulevard, secretaries were beginning to grow anxious, restless for their two-hour midday siesta to begin. At the National Pawnshop, Monte de Piedadthe Mountain of Pitypeople stood waiting their turn, holding musical instruments and cartons containing anonymous family treasures.

A taxi, one of the salmon-colored sedans that loiter outside the big downtown hotels which cater to foreign tourists, threaded its way through the clotted queues of cars, trucks and buses on Reforma. Just as it was about to be swallowed up in the whirlpool of traffic swirling around the entrance to the park, the passenger in the back seat of the cab leaned forward and told the driver to stop. He was a small, chunky man. So small, in fact, that when he got out of the taxi someone seeing him from behind might have guessed that he was a grade-school pupil on his way home to one of the grand houses concealed behind high walls on the side streets in the neighborhood. But when he turned around, a stranger, expecting to see a child, would have seen a moustache and the weathered complexion of a man who four days earlier had turned twenty-five and who, indeed, looked older than that. Although he was short, he had broad shoulders and a thick torso that seemed out of proportion to the rest of his body; brown hair flopped over his forehead and curled around his ears, landing half an inch above the collar of a brown sport coat; above his bushy moustache there were turquoise eyes that seemed at once too large and more moist than they should have been.

He walked three blocks to Calzada de Tacubaya, a wide expressway now almost hopelessly congealed with late-morning traffic, and turned toward a three-story white building. It was a big, brooding fortress of a place half hidden behind trees with a forest of radio antennae bristling from the roof and a plaque on an outer wall that read:

EMBAJADA

DE LA UNION DE LAS REPUBLICAS

SOCIALISTAS SOVIETICAS

It was the Soviet Embassy. He walked along the sidewalk in front of the wall and then paused; through a row of iron bars, he studied a small guardhouse set back from the street for several moments. Then he scanned the upper floors of the main building. For a moment he thought he saw a curtain jiggle at one window and the face of a man looking at him; but the face vanished suddenly. After a full minute, he started walking again. But before he took more than a few steps, he saw a limousine slowing to enter the compound and he rushed to intercept it. But the car didnt stop and it quickly disappeared behind a wall. He lit a cigarette, looked around and casually lobbed a ball of paper through the iron bars.

Before he could walk thirty paces, a Mexican policeman ran up and ordered him to halt. He protested that he was a tourist from California who had gotten lost while seeing the sights of Mexico City. But two hours later he was under arrest at the Metropolitan Police Headquarters of Mexico City, accused of murder.

As he waited to be questioned, he could recall his first visit to the Embassy. It had been simple then: He had presented himself to the clerk at the reception desk in the guardhouse, thrown down the computer programming cards and said, I have a friend with socialist leanings who would like you to have some information. The clerk shook his head and said he didnt speak English and left to get someone who did.

He had sat in the stark lobby of the building, his feet barely reaching the floor, looking up at a portrait of Lenin on the wall. When he was sure no one was watching him, he raised the Minolta that he had hung around his neck to look like a tourist and snapped a picture. Who knows? he thought. Someone might be willing to pay for a photograph of the inside of the Russian embassy.

Twenty minutes later he met Okana.

Vasily Ivanovich Okana was listed with Mexican authorities as a vice consul of the Soviet foreign service. He was in fact a member of the Soviet intelligence service, the KGB. At that first meeting, the American had not been much impressed physically by the slender man in the poorly fitting black suit. Later he had learned that beneath the baggy suit was the muscled physique of a fitness fanatic.

These are interesting, the thirty-eight-year-old KGB agent had said in English as his fingers played with the computer cards. But what are they?

He was only a courier, he replied, but it was his understanding that they had something to do with what people called spy satellites.

The Palos Verdes Peninsula is in Southern California. From the air it looks like the jagged prow of a huge ship trying to escape from the rest of North America. It rises like a rocky, slab-sided Gibraltar at the southern entrance to Santa Monica Bay and at sunset glows with soft shades of orange reflected by thousands of Mediterranean tile roofs. Nine miles long and four miles wide, the mountainous Peninsula lifts up and away from the table-flat Los Angeles basin, establishing physical and social isolation from the freeway culture of that city. The isolation was created eons ago by geological forces and by centuries of sedimentation, erosion and waves that sculpted a land of scalloped coves, terraced cliffs and rocky headlands above lonely beaches strewn with pebbles and driftwood.

For centuries its remoteness resisted efforts to populate the Peninsula. It was like a vast feudal grazing land, producing hides, tallow, beef and, later, vegetables tended by immigrant tenant farmers from Japan. But after World War II, when Los Angeles was becoming the prototype of modern urban sprawl, more and more people who had emigrated to that city became disenchanted with its version of the California Dream, and many began to colonize The Hill, as its inhabitants came to refer to their refuge from the sprawl. As time went on, the Palos Verdes Peninsula became a prestigious address, and as it did, many colonizers of The Hill began to look down, in more than one way, on the people who lived below on the flatlands of the basin.

The immigrants to The Hill were, for the most part, college-educated people from out of state who had come to California with little more than their brains and their ambition. And they had found success that allowed them to afford a place on The Hill. They were achievers who accumulated money, most of them, not through inheritance or bloodlines but through their own talents, drive and ambition. Many prospered in the aerospace industry at companies like North American Aviation, Douglas Aircraft, Hughes Aircraft, TRW Systems and other firms that built airplanes, missiles, space satellites and electronic gadgetry down on the flatlands. In the years after the war, aerospace ballooned into a prosperous industry as specialized and concentrated as Detroits, and Palos Verdes became its Bloomfield Hills.