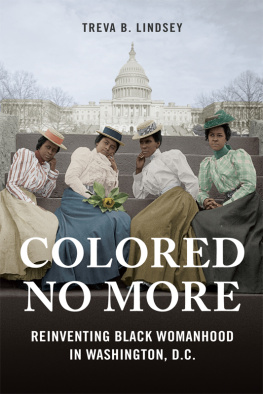

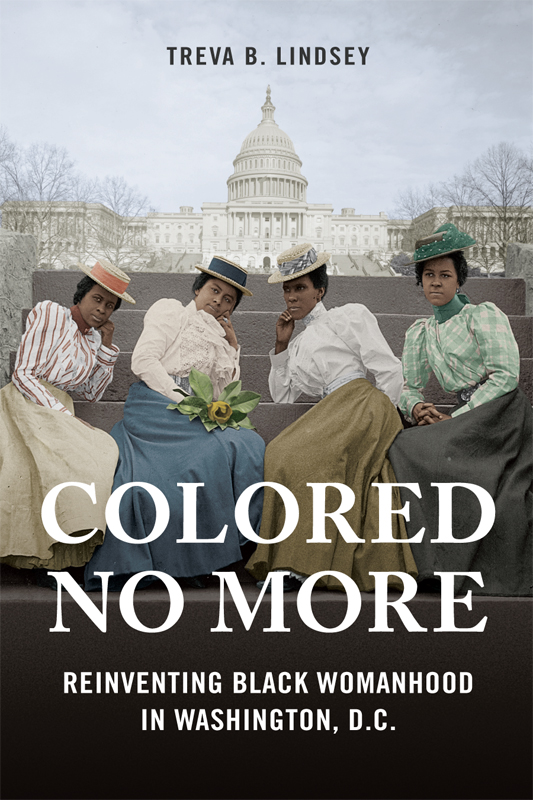

Colored No More

WOMEN, GENDER, AND SEXUALITY IN AMERICAN HISTORY

Editorial Advisors:

Susan K. Cahn

Wanda A. Hendricks

Deborah Gray White

Anne Firor Scott, Founding Editor Emerita

A list of books in the series appears at the end of this book.

Colored No More

Reinventing Black Womanhood

in Washington, D.C.

TREVA B. LINDSEY

2017 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lindsey, Treva B., 1983- author.

Title: Colored no more: reinventing black womanhood in Washington, D.C. / Treva B. Lindsey.

Other titles: Reinventing black womanhood in Washington, D.C.

Description: Second edition. | Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, [2017] | Series: Women, gender, and sexuality in American history | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016045891 (print) | LCCN 2016056612 (ebook) | ISBN 9780252041020 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780252082511 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780252099571 (e-book : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780252099571 (E-book)

Subjects: LCSH : African American womenWashington (D.C.)History. | Women, BlackRace identity. | African American womenWashington (D.C.)Social life and customs. | African American womenPolitical activityWashington (D.C.)History20th century. | WomenSuffrageWashington (D.C.)History20th century. | WomenWashington (D.C.)History. | Washington (D.C.)Social life and customs20th century. | Washington (D.C.)Politics and government20th century. | SalonsWashington (D.C.)History20th century. | Washington (D.C.)Intellectual life20th century.

Classification: LCC E 185.93. D 6 L 56 2017 (print) | LCC E 185.93. D 6 (ebook) | DDC 305.48/8960730753dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016045891

For Relisha Rudd

Contents

Acknowledgments

I never dreamed of writing a book. Even as a graduate student in the Department of History at Duke University, I did not foresee using my research on black women living in Washington, D.C., during the early twentieth century for any kind of manuscript. The amazing women of my birth city, however, ended up enveloping my life. I could not put them or their stories away without digging deeper into what it meant to be a black woman moving through the city that gave me life. I would see their names on schools, on street signs, and on buildings throughout the city. I wondered. I mused about their livestheir untold stories. I knew I walked among greatness every time I set foot on Howard Universitys campus, strolled along U Street in search of the best after-hours spot, or indulged in a little retail therapy in Georgetown. I also knew violence, pain, discrimination, inequality, and loss inscribed the lives of generations of black women before me. The legacy of slavery, Jim Crow, race riots, and postindustrialization was visible throughout the city. By the time I was born, the ravages of the War on Drugs, mass incarceration, white flight, and resegregation were evident on my street corner across from the Shrimp Boat in northeast Washington and on far too many corners throughout the nations capital. This was Chocolate City, and she had many stories to tell.

My parents encouraged me to pursue my research interest in Washington. They never doubted the significance of this project. Without knowing much about the manuscript-writing process, they helped me see the project that would become this book. Like so many other moments of my life, my parents advised and inspired me. They cheered for me and told me to follow my heart. Throughout graduate school and my tenure as a professor, Anthony and Treva Lindsey were my rocks. They were my biggest cheerleaders and unabashedly my greatest fans, and I could not imagine a single page of this book being written without their love and continued support at every stage of my life. I have to thank my godparents Cheryl and Kevin Brown and Cheryl and Tony Santos for always being there. Uncle Stan Jackson and Auntie Nicey Jackson were my other parents from day one. They never fail to tell me how proud they are of me. To my sisters: Talia, Chenise, and MiracleI am grateful for all of you. To my brothers, Stanley and Marcus Jacksonthank you for always riding for me. My aunts, Sarah McCrae, Louise Hodge, and Linda Blunt, and my Uncle Hayves have always cheered the loudest for me. My grandmothers, Lula Pearl, Bertha Lindsey, and Ella Ruth Streeter, instilled lifelong lessons of humility, tenacity, and kindness into me. I hope this book is a testament to the unconditional love I hold for my family.

My advisors also provided me with invaluable guidance, mentoring, and tough love. Laura Edwards, Adriane Lentz-Smith, Davarian Baldwin, and Mark Anthony Neal were the best committee members one could hope for. Laura worked closely with me on every chapter, offering critical feedback and generous line editing. Her support of my work did not cease after I graduated. Adriane joined my committee soon after she arrived at Duke University, and I could not be more grateful. Her thoughtful feedback and incisive questions on each chapter sharpened my voice as an author. I am so glad she came to Duke when she did. Reading Davarians book on New Negroes in Chicago changed the game for me. I was ecstatic when he agreed to serve on my committee and overjoyed at how engaged he remained with my project at every stage. Last, but certainly not least: Mark. There are no words to describe how much I value him as an advisor, colleague, and mentor. He added something so special to my process and to this book. I could never overstate how amazing it was and is to have this wonderful group of scholars invested in me.

At Duke, I also had the pleasure to learn from, study alongside, and work with amazing graduate students and faculty members. I want to thank my informal cohort of amazing graduate-school peers, including Tami Navarro, Alexis Gumbs, Bianca Williams, Jenny Woodruff, Marti Newland, Britt Russert, Alisha Gaines, Micah Gilmer, Reena Goldthree, Danielle Terrazas-Williams, Felicity Turner, Kinohi Nishikawa, and Samantha Noel for all of their brilliance and kindness during one of the toughest journeys of my professional life. Faculty members Wahneema Lubiano and Maurice Wallace sharpened my skills as critical thinker. The Department of African and African American Studies at Duke provided a second home for me at the university. This department also pushed me to develop into an interdisciplinary scholar. The entire faculty and staff of AAAS at Duke enhanced my experiences as a graduate student. I want also to thank the John Hope Franklin Scholars Program and the Reginaldo Howard Scholars program for allowing me to serve as graduate assistant during my time at Duke. Both of these programs helped me become a more well-rounded scholar.

Prior to arriving at Duke for graduate study, I had the pleasure of learning from some of the most amazing scholars in the world at Oberlin College. I did not consider a career as a professor until I had the pleasure of taking classes and studying with Drs. Meredith Gadsby, Caroline Jackson-Smith, and Pamela Brooks. These three women changed the game for me. Seeing such brilliant and fly black women scholars inspired me. They each encouraged me to think seriously about graduate school and pointed me toward the Mellon Minority (now Mays) Undergraduate Fellowship program. I had no idea applying for and being accepted into the MMUF program would literally change my life. Thank you Monique, Janene, and Clovis for making me part of the MMUF family. This program taught me how to do graduate level research, funded summer research, assisted me in applying for graduate school, provided crucial financial support during my tenure as a graduate student, helped me write a proposal, and guided me through the academic job-market process. Additionally, being part of the MMUF program made me part of a family. Two of my most prized interlocutors and dear friends came from MMUFDrs. Jessica Johnson and Uri McMillan. You are my rocks and have been for more than a decade.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.