1994, 2010 by the Smithsonian Institution.

All rights reserved

Copy Editor: Karin Kaufman

Production Editor: Jenelle Walthour

Designer: Janice Wheeler

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Clark-Lewis, Elizabeth.

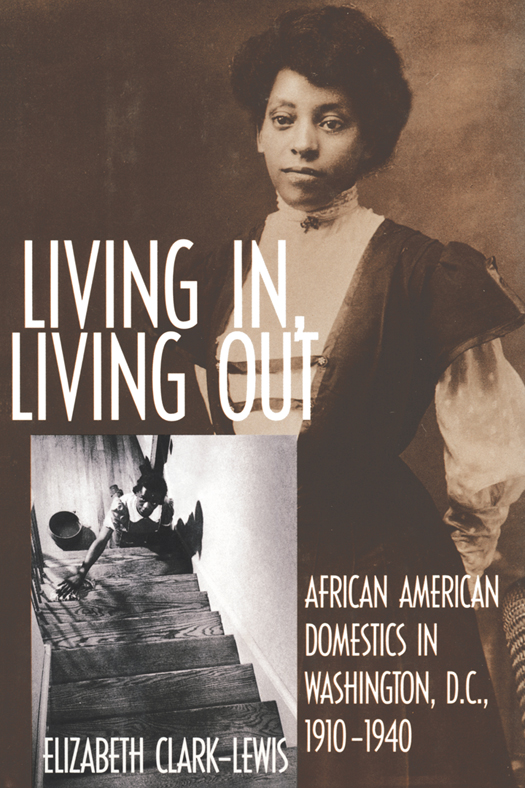

Living in, living out: African American domestics in Washington, D.C., 19101940 / Elizabeth Clark-Lewis.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 1-56098-362-0 (cloth)

eBook ISBN: 978-1-58834-442-7

1. Women domesticsWashington (D.C.)History20th century. 2. Afro-American womenEmploymentWashington (D.C.)History20th century. I. Title.

HD6072.2.U52W183 1994

331.4816904609753dc20

94-14415

A paperback reissue (ISBN 978-1-58834-286-7) of the original cloth edition.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data is available.

For permission to reproduce illustrations appearing in this book, please correspond directly with the owners of the work, as listed in the individual captions. (The author owns the rights to the illustrations that do not list a source.) Smithsonian Books does not retain reproduction rights for these illustrations individually or maintain a file of addresses for photo sources.

v3.1

TO

LAWRENCE J. LEWIS

AND

ABENA M. S. LEWIS

CONTENTS

1.

GOD AND THEY PEOPLE: THE RURAL SOUTH

2.

WHOD HAVE A DREAM? THE MIGRATION EXPERIENCE

3.

NEW DAYS DAWNING: THE WORLD OF WASHINGTON

4.

A ENDLESS MIRATION: LIVE-IN SERVICE

5.

THE TRANSITION PERIOD

6.

THIS WORK HAD A END

7.

KNOWIN WHAT I KNOW TODAY

8.

THE SOUND STAYS IN MY EARS

PREFACE

T he pictures of women in my family are portraits of persons who defiantly believed you worked to survive. Their lives were full of family work, community work, church work, work-work, and more work. My mother spent four of her forty-five years of employment as a dayworker. My grandmother, Katie Chivis, had been a live-in servant for eight yearsuntil her marriage and migration to Pennsylvania in 1916. My great-grandmother, Eliza S. Johnson, was born a slave in Virginia in 1853. After the end of slavery, she worked sixteen years as a servant and an additional sixty as a washerwoman while bearing a child every twenty-three months, rearing seventeen children, and mothering her husbands other sixteen children. My great-great-grandmother, Miss Winnie, was a slave in Fauquier County, Virginia, until 1865. She worked as a servant for twenty-two of the twenty-four years she lived after emancipation.

I knew all these womens names but only some of their stories. As a child I loved to sit and listen as my mother, aunts, and their friends talked about their daywork stories. Each story had an Anansee quality to it; the African American poor girl outwits Miss Ann in the end.

When my great-aunts visited Pennsylvania, however, they told stories far better than those of my mother and her sisters. They talked about live-in service and chided the women of my mothers generation for not knowing hard times and for never having to work day and night on a stay-in job for twenty-five cents a month. They made my mothers ten-to-twelve-hour work days and two dollars a day appear to be a great improvement. They openly lamented missing the money and better daywork-work era of the women of the Depression! Then they always ended with a prayer of thanks for not having been slaves. They talked for hours, comparing their mothers and grandmothers plight to that of women born after slave times.

Writing a book about these women and the work they performed demanded extensive research. Using the existing histories, I learned about the great womenthose with well-known namesand their contributions to history in spite of the double confinements of discrimination and oppression, but not about women like my ancestors, living relatives, and neighbors. Where were they in the books, where were their voices? This book tries to recover those voices.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

T hey came from Midnight, Mississippi, and Dawn, Virginia; they told about families left behind in Blackman, Florida, and Whitesville, Kentucky; they shared the secrets of African American culture learned in Faith, North Carolina, and Hope, Texas. First and foremost, it is to these women I extend my thanks. My debt is deep to all of the women who agreed to be interviewed for this book. They unselfishly gave their time, shared with me their history, and filled in the gaps of my history. Without the willingness of each of them to be interviewed, this book would not exist. They helped me travel to different places, explore new worlds, and understand life for women reared eighty to more than a hundred years ago. They enriched my understanding of the past and deepened my appreciation of the many ways young African Americans owe a debt of gratitude to them all.

Mrs. K. Elizabeth J. Campbell helped me to arrange my first family interviews. She also shared her insights on many sensitive local historical points during the project, and gave this manuscript its final review. Her seventy-six years of wisdom helped me, and I thank her. Betty Robertson and Kenneth Banks each introduced me to ten women, and the twenty interviews they made possible are the core of my research. These two friends have been essential to this books development. My special thanks go to the following for their invaluable contacts and assistance: Elaine Blackwell, Delta Towers Senior Citizens Residence; Rosetta Bailey, Pendleton House Senior Citizens Residence; Ellen Killens, Portner Place Senior Center; LaShawn Bynum, Campbell Heights Senior Center; Carmen James Lane and Thelma Russell, Potomac Gardens Senior Citizens Council; Gwendolyn Coleman, Columbia Heights Senior Citizens Center; Ruth DeBerry, Pentacle Senior Citizens Center; Brenda Tucker, First Baptist Senior Center; Carolyn Mills-Bowden, Washington, D.C., Office on Aging; Seniors Coalition, James Creek Public Housing Community Center; and the Senior Citizens Club, Shiloh Baptist Church.

Many scholars have kindly shared their research with me, always going beyond the ordinary requirements of scholarly pursuit: Drs. Phyllis Palmer, Faye Dudden, Robert Hall, Jacqueline Jones, Daphaney Harrison, Paul Phillips Cook, Debra Newman Ham, Thomas Battle, Walter Hill, and Pamela Ferrell; Artie Myers, Library of Congress; Karen Jefferson, Director of the Manuscript Division, Moorland Spingarn Research Center; Roxanna Deane, Director, and Mary Ternes, Photo Librarian, in the Washingtoniana Division, Martin Luther King Memorial Library, Washington, D.C.; and the staff of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture.

Mark Hirsch of the Smithsonian Institution Press supported this project and made its completion possible. The cogent editing skills, suggestions, and directions of Jenelle Walthour, Judith Sacks, and Karin Kaufman immeasurably improved the final draft of the manuscript. The critical judgment and literary suggestions of Elizabeth F. Rankin and Carmen Lattimore shaped the early drafts of the manuscript. The keen eye and good judgment of Jeff Fearing assisted me in all aspects of my photograpic research work. I thank Tamas deKun for his photo-copying workmanship. Friends Yvette Murphy Aidara, Barbara Carter, Dureau Smith, and my niece, Kim Williams, each read, re-read, and re-reread drafts. For their support I am grateful.