Introduction

But this is nowyou may depend upon it

Stable, opaque, immortalall by dint

Of the dear names that lie concealed within't

EDGAR ALLAN POE,

AN ENIGMA

Pamela Hill died on March 22, 2000, sixty-one years almost to the day after she first fell in love. It had been a coup de foudre, a blinding revelation, in the course of a dance, and from that moment she was never out of love. She experienced love in many different guises, as joy, agony, despair, renewal, but never did she find it sweet and sugary. There was only one person she loved, and constancy gave to that single attachment a quality that was epic in its depth and passion.

Donald Hill was a young pilot in the Royal Air Force, who had just gained his wings. She was a fashion model with, as she said, no interests except having fun. They were both in their twenties. Initially, at least, the connection might have amounted to no more than a romantic infatuation, the sort of romance that begins in spring and is finished by the end of the year. But neither of them had ever been in love before. And this was March 1939. What happened between them when they first danced together was to shape her life up to its very last days.

The shadow of war hung over them. There was nothing strange in that. It was the fate of an entire generation to live with the knowledge that the world was out of control. Like other lovers, Pamela and Donald tried to ignore it, as though the high intensity of their feelings could keep the future at bay. What made them different was not something that could be recognized quickly. It was hardly apparent when war broke them apart, separating and scarring them, and it was only beginning to emerge when they found each other again after peace returned. In a way that later generations, searching for immediate fulfillment, would find increasingly hard to understand, it was a matter of keeping the faith whatever it cost. And that was what finally became abundantly clear in the last days of Pamela's life.

She had found her love in that first giddy dance. He made her feel complete as no one else did. To have him and keep him, she had to create an emotion that was more powerful than war, whose coherence outreached the chaos that drove them apart, whose compassion lasted longer than the madness inflicted by the prolonged cruelty of a prison camp. It had to fill absence, to heal wounds, and to make sense of two mortal, misspent lives. And to do that it had to be constant to the very end.

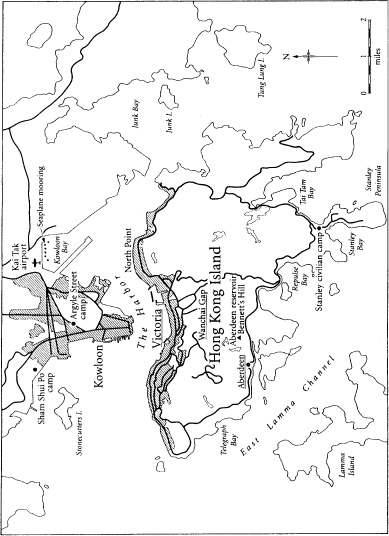

There was a mystery about what happened to Donald after the fighting swallowed him up in December 1941. Barely three months after meeting Pamela, he had been sent to join British forces in the Far East. On that infamous day when Pearl Harbor was bombed, the Japanese also invaded Hong Kong, where he was stationed. Here, too, they achieved surprise, and after seventeen days of fierce battle the garrison surrendered on Christmas Day. The surviving defenders, including Flight Lieutenant Donald Hill, were taken prisoner.

Among the possessions he carried with him into captivity was a diary. He had begun it the day before the Japanese attacked. Much talk about war with Japan, he wrote, and then added guardedly, but no one seems to think anything will happen.

His opening words offer a misleading clue to the writer's enigmatic character. Almost all Westerners thought, as he did, that however warlike the Japanese might appear, they did not want to fight quite yet. Thus anyone able to read what he had written might reasonably have concluded that this was the work of a conventional man. That impression, of being quite ordinary, would have suited Donald Hill. For most of his life he had attempted to disguise himself, hiding his feelings, concealing his ambitions, narrowing the scope of his desire to what was reasonable and attainable. After a childhood overshadowed by tragedy, and a deeply inhibited upbringing, he had dutifully begun his adult years by training to become an accountant. Nevertheless, if only for the intensity of the passion and sensuality that he had begun to sense within him, he could not be called a conventional man.

He had reached his mid-twenties when by chance he stumbled into joy. It came first from learning to fly, and nothing had prepared him for the sense of liberation he felt in the air. Yet even that did not compare with the lightness of being that followed with the discovery that he was in love. The electric moment of their first dance and the golden summer that followed lifted him from the cramped loneliness of what had come before to dizzy heights of happiness. For the rest of his life the sensation was to stay with him as something beyond compare.

Posted to the Far East, he could still fly, but being in love had become less easy when Pamela was six thousand miles away. His instinct was to conceal the power of his frustration. He developed a manner that was very privatethe characteristics that his colleagues particularly noticed in him were his quietness and his competencewhile his letters to Pamela were cheerful and full of anticipation of their future together. But he could not hide from himself either his unhappiness and his yearning to be with her, or the fact that during his two years' absence he had not been faithful.

When he began his diary, he was in command of a flight of five aircraft which represented Hong Kong's only air defense. Since the planes were old and slow, and had repeatedly been condemned as obsolete, he knew that his chances of survival in combat would be small. He was not yet thirty. If he did not live to see Pamela again, he would at least leave a record to tell her what had happened to him.

By a miracle, he came through the fighting unscathed, and was eventually to emerge alive from a Japanese prisoner-of-war camp. Yet he was not the same. That was the mystery. What had changed him? If there was any sort of answer, it had to be in the diary.

Married and with three children, Donald and Pamela carried their past, with its extremes of emotion, into middle age. Long years had come between their engagement in 1939 and their wedding in 1946. Like many of that generation they coped with the injuries of war by an effort of self-control that seemed alien to their children, growing up in the 1960s. But the pain of what Donald had suffered was not the less for being rarely expressed.