THE FABRIC

OF AMERICA

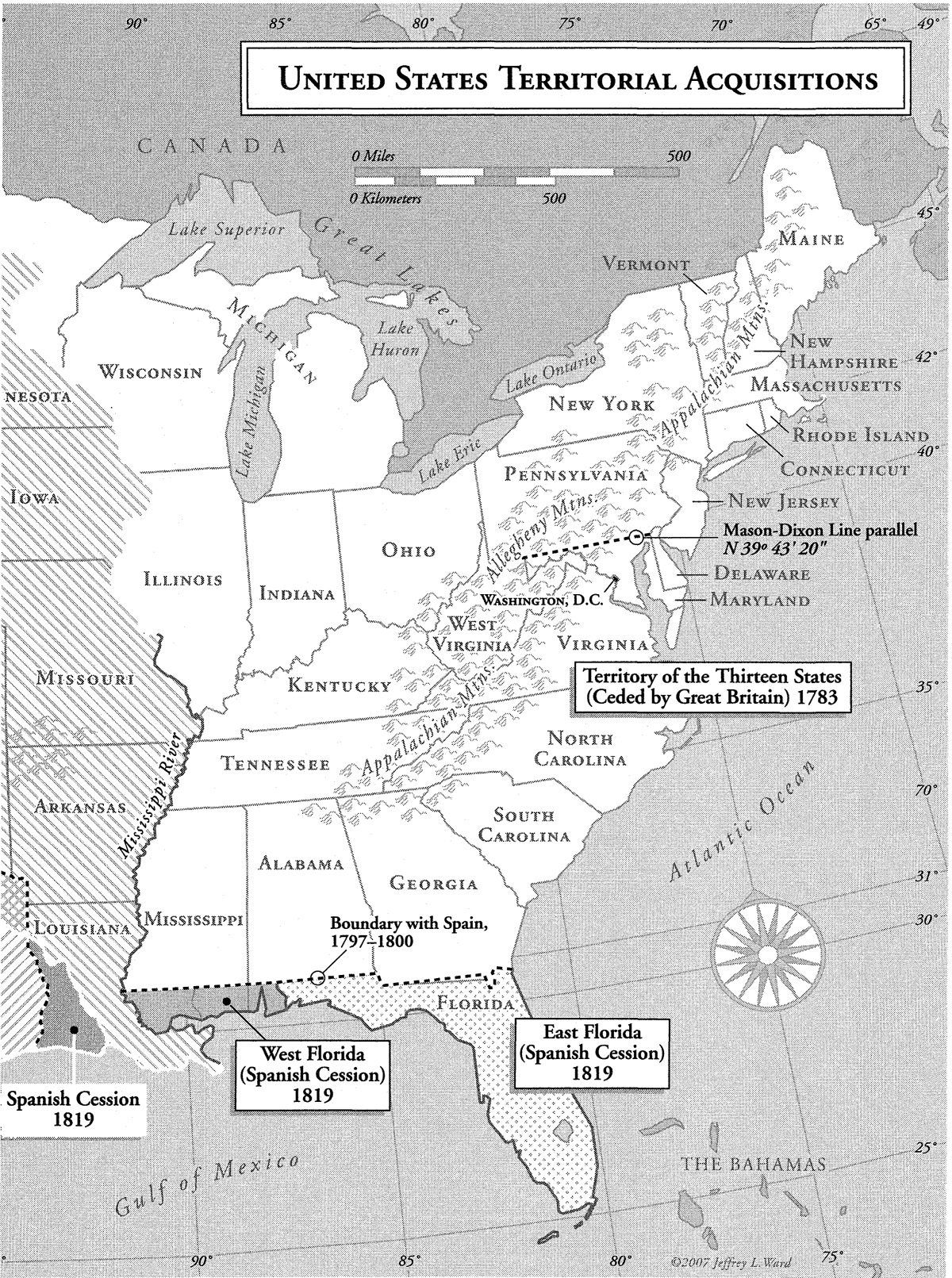

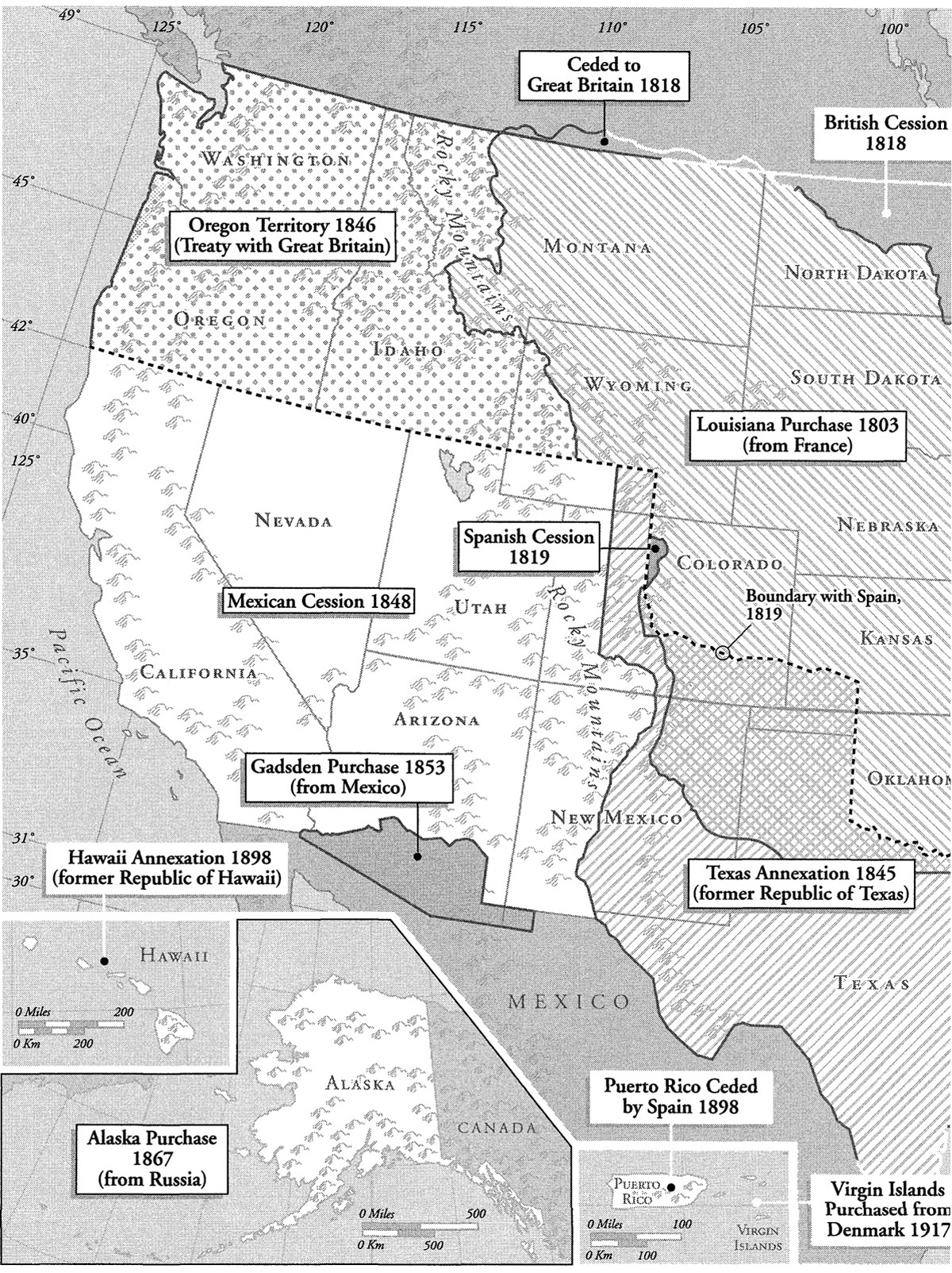

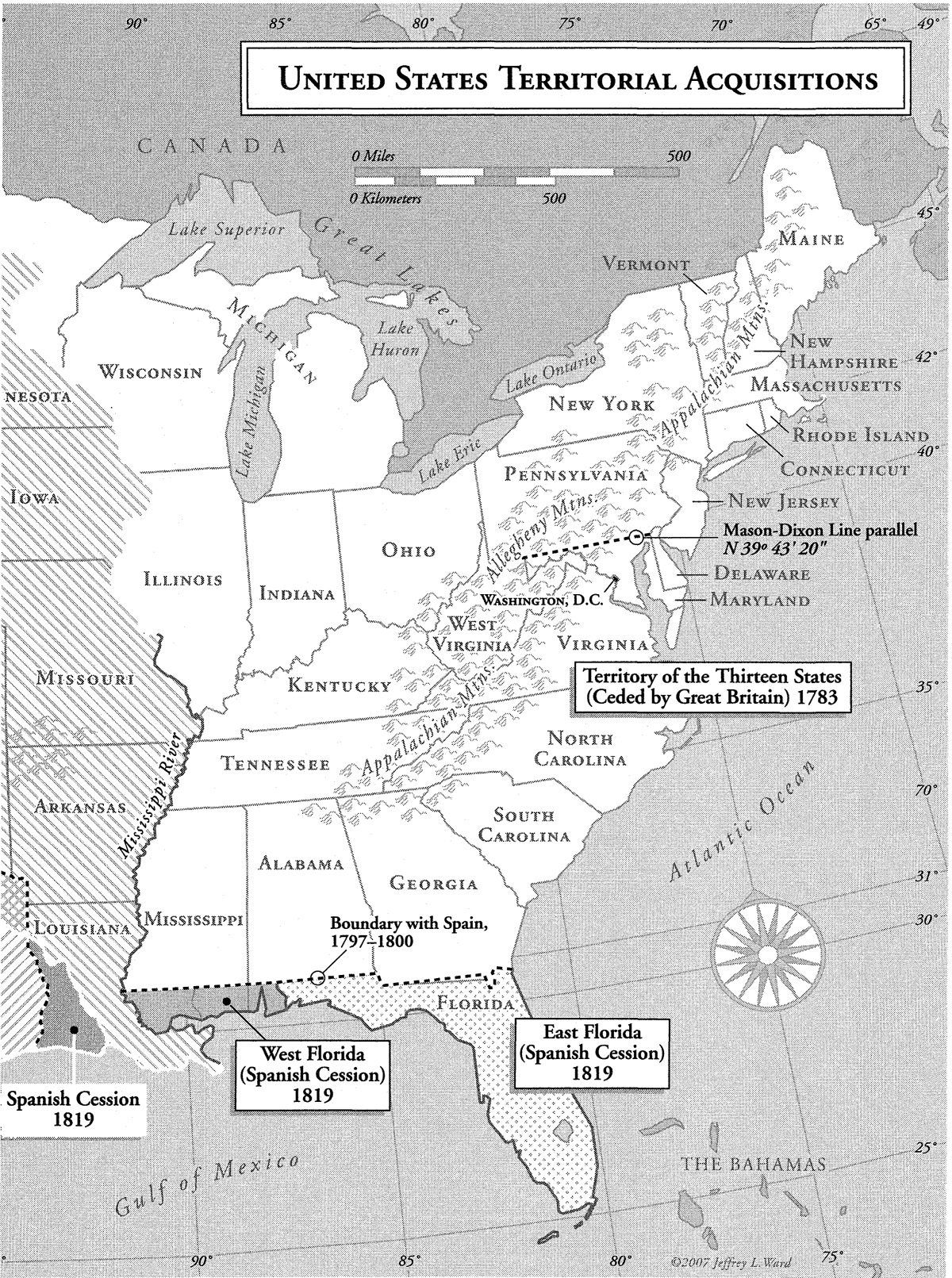

How Our Borders and Boundaries

Shaped the Country and Forged

Our National Identity

ANDRO LINKLATER

Copyright 2007 by Andro Linklater

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information address Walker & Company, 104 Fifth Avenue, New York, New York 10011.

Published by Walker & Company, New York

Distributed to the trade by Holtzbrinck Publishers

Artcredits: Jeffrey L. Ward. Library of Congress. Smithsonian Institution. Charles Townsend. Science Photo Library. Massachusetts Historical Society. Wisconsin Historical Society. Michele Lee Amundsen.

All papers used by Walker & Company are natural, recyclable products made from wood grown in well-managed forests. The manufacturing processes conform to the environmental regulations of the country of origin.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been applied for.

eISBN: 978-0-802-71850-1

Visit Walker & Company's Web site at www.walkerbooks.com

First U.S. edition 2007

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset by Westchester Book Group

Printed in the United States of America by Quebecor World Fairfield

CONTENTS

The forests and desarts of America are without landmarks... It is almost as easy to divide the Atlantic Oceanby a line, as clearly to ascertain the limits of those uncultivated,uninhabitable, unmeasured regions.

DR. SAMUEL JOHNSON, The Literary Magazine, 1756

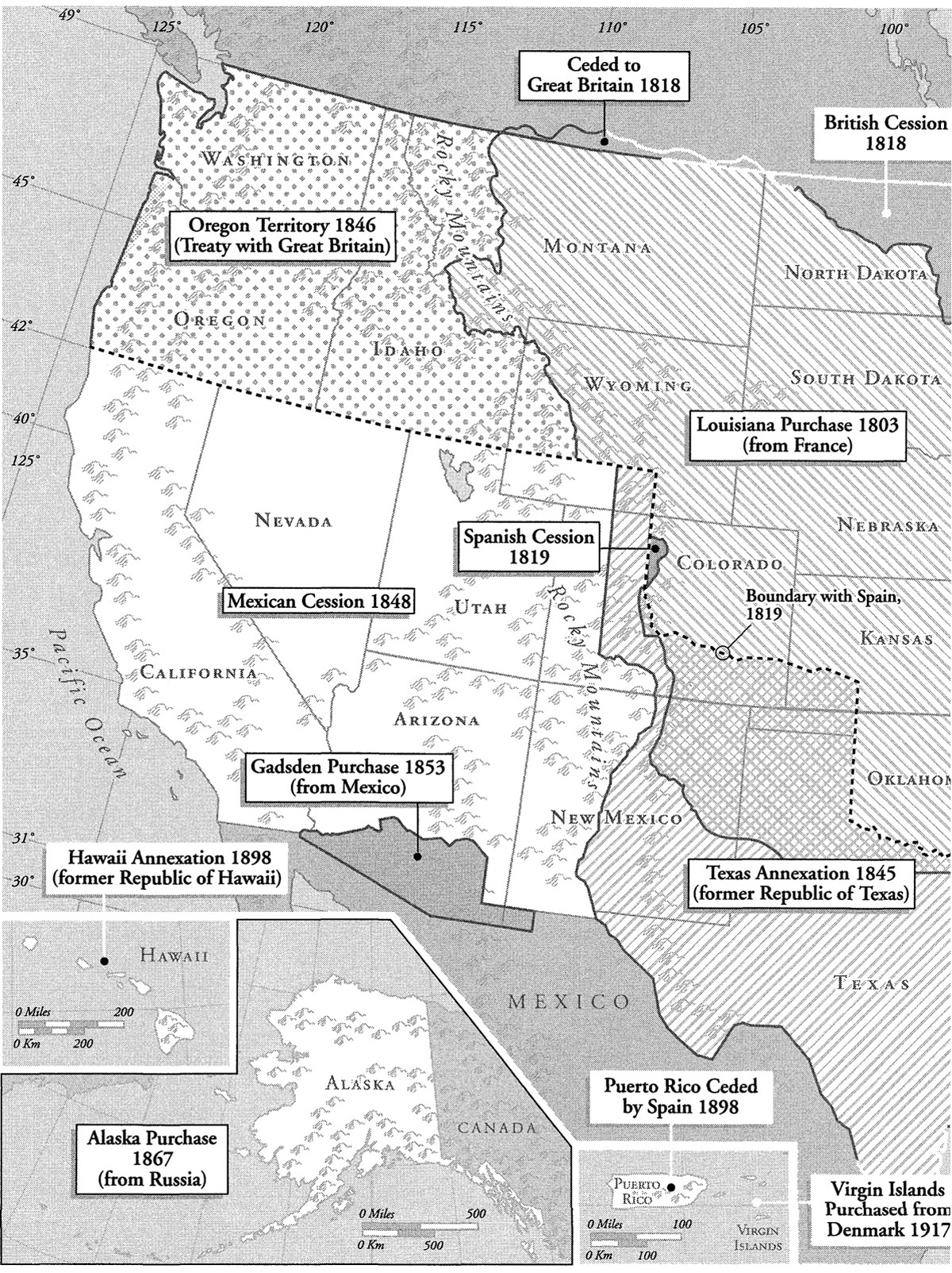

T RAPPED IN SIX lanes of traffic, most drivers look impatient or bored as they inch toward the San Ysidro crossing point between the United States and Mexico. A few faces appear anxious. Not one expression conveys surprise. Yet the changes that have happened here in the last few years should be cause for astonishment. A border, once not much more than a line of glass-fronted booths, has become a frontier. Everywhere there is extra security. Black-lensed cameras track the lines of vehicles. Uniformed patrols check registration numbers against computer records. Unsmiling immigration officers inspect faces and documents suspiciously.

Out in the desert, the signs are more dramatic still: fences, watchtowers, heat sensors, armed vigilantes, border guards, even detachments of the National Guard. Never before in peacetime has the United States devoted so much effort and money to the defense of its national frontier. For most of the last century, the line that demarcates the limits of the nation has hardly entered public consciousness. As drivers wait in the simmering heat for the detailed examination of the car ahead to be completed, the paradox suddenly becomes glaringly obvious. What now rates as the most urgent priority on the political agenda is the zone that history forgot.

The moment that the U.S. frontier disappeared from the radar screen can be placed almost exactly. On November 4, 1892, the Aegis, a student newspaper published by the University of Wisconsin, carried an article entitled "Problems in American History." Its brash young author suggested that too much attention had been directed by historians to the formal boundaries that divided and delineated the United States. The epitome of the historian he had in mind was Professor Hermann von Hoist, who earlier that year had published the seventh and final volume of his monumental work, The Constitutional and Political History of the United States.

In his history, Hoist concentrated upon the powers contained within state and national frontiers, arguing that the unique character of the United States emerged from the bitter fight for constitutional dominance between state and federal governments. It was this perspective on American history that the article in the Aegis attacked. It condemned "the attention paid to State boundaries and to the sectional lines of North and South" and asserted that the United States owed its unique character to the influence of another, less formal frontier, the line of settlement that "stretched along the western border like a cord of union." Seven months later, on July 12, 1893, the writer, Frederick Jackson Turner, professor of history at the University of Wisconsin, presented his thesis to a wider audience, the American Historical Association in Chicago, under a title that was to become famous: "The Significance of the Frontier in American History."

The San Ysidro crossing represents everything that Turner set out to bury. "The American frontier is sharply distinguished from the European frontiera fortified boundary line running through dense populations," he insisted. "The most significant thing about the American frontier is, that it lies at the hither edge of free land."

It was here that the American character was formed, Turner argued. Whatever their national origin, the settlers became infected with the frontier spirit"that restless nervous energy, that dominant individualism working for good and for evil, and withal that buoyancy and exuberance which comes with freedom"and thereby acquired a common identity. In short, it was in "the crucible of the frontier [that] the immigrants were Americanized."

For more than a century Turner's thesis has loomed over the history of the western United States like a battle-scarred colossus. It has been repeatedly assaulted by professional historians for the way that it airbrushes the Native American experience out of the records, leaves unexamined the contributions of women and frontier communities like the Germans and Mormons, and fails to explain why similar experiences on other nineteenth-century frontiers in Siberia, Australia, southern Africa, Argentina, and Canada conspicuously failed to Americanize those pioneers. But however much it is battered, Turner's argument has refused to fall down, if only because the opening up of the west did profoundly affect the rest of the country and did call forth a specifically American response.

In popular consciousness, therefore, Turner's frontier has until now remained unchallenged. The term continues to be automatically attached to such boundless areas as outer space, the Internet, or intellectual property, implying that here are fresh and unlimited opportunities particularly suited to exploitation by American enterprise and adaptability. The spirit it engendered remains the default explanation for what makes America different from the rest of the world.

In the era of terrorism and mass immigration, however, a seismic shift is clearly taking place. It is the older meaning of frontier that draws public attention, the line that delineates an area of sovereignty. The history of that frontier began with the first generation of Americans. They had fought to win sovereignty from the Britishthe right to establish for themselves democratic government and individual liberty. To mark out the scope of that sovereignty, lines had to be drawn in the ground. Among the many consequences of independence, therefore, few were more significant than the curious ritual that took place in the summer of 1784 on top of Mount Welcome, a commanding height in the Allegheny Mountains in what is now West Virginia.