Contents

Maps vii

Acknowledgments x

Introduction xii

Don't Skip This

ALABAMA 11

ALASKA 18

ARIZONA 21

ARKANSAS 27

CALIFORNIA 33

COLORADO 39

CONNECTICUT 44

DELAWARE 52

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA 59

FLORIDA 65

GEORGIA 70

HAWAII 75

IDAHO 79

ILLINOIS 86

INDIANA 92

IOWA 95

KANSAS 101

KENTUCKY 108

LOUISIANA 113

MAINE 119

MARYLAND 126

MASSACHUSETTS 134

MICHIGAN 141

MINNESOTA 145

MISSISSIPPI 151

MISSOURI 156

MONTANA 163

NEBRASKA 168

NEVADA 174

NEW HAMPSHIRE 179

NEW JERSEY 185

NEW MEXICO 192

NEW YORK 197

NORTH CAROLINA 206

NORTH DAKOTA 216

OHIO 220

OKLAHOMA 226

OREGON 231

PENNSYLVANIA 236

RHODE ISLAND 243

SOUTH CAROLINA 248

SOUTH DAKOTA 253

TENNESSEE 257

TEXAS 263

UTAH 270

VERMONT 276

VIRGINIA 281

WASHINGTON 288

WEST VIRGINIA 294

WISCONSIN 298

WYOMING 303

Selected Bibliography

Index

About the Author

Credits

Cover

Copyright

About the Publisher

Maps

In memory of Caroline Newman 1951-2008

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the men and women of the U.S. Geological Survey who created the National Atlas of the United States. This interactive Web site has been of immense value to me in preparing this work. Of even greater value has been Caroline Newman, Executive Editor at Smithsonian Books. I now know what authors mean when they praise their editors for having vitally important insight and perseverance. I am also deeply indebted to our copyeditor, Cecilia Hunt, and to our cartographer, Rob McCaleb of XNR Productions, whose keen eyes not only detected errors but also led me to new discoveries. And lastly, my heartfelt thanks to Arlene Balkansky of the Library of Congress, who is my wife. I would urge any young person entering a career that involves research to marry an employee of the Library of Congress.

I am also deeply indebted to the Geography and Map Division at the Library of Congress, whose online historical maps provided a treasure trove of information, and whose reference staff led me to resources without which I never would have found the reasoning behind several state borders.

Following this book's initial publication, a number of readers called my attention to various oversights. These readers include every member of my family. For these contributions, I want to thank my wife, my sons, Harry and David, and my sister, Roberta Redfern. I also want to thank Marcia Bjornerud, Douglas F. Burns, Eugene Fernstrom, Daniel L. Goldberg, James Hand, Manus Hand, Jamie Heller, Keith Karamanos, Jack Ritterskamp, Michael Rodman, Robert C. Ross, and Peter G. Wolfe. I am especially appreciative of insights I received from Stan Vitton regarding the boundaries of Georgia and Alabama.

Introduction

To teach us the boundaries of the states, my seventh grade geography teacher would hold up cutouts and we would raise our hands, vying for the chance to identify which state had the corresponding shape. How we distinguished Wyoming from Colorado, both rectangles, eludes me these many years later. Maybe she just didn't include them. After all, how much value is there in knowing which rectangle is Wyoming and which is Colorado?

Later in life, I came to realize that there is value in learning about the borders of Colorado and Wyoming, but that value resides, not in knowing what their shape is, but in knowing why it is. Why, for instance, are the straight lines that define Wyoming located where they are and not, say, ten miles farther north or west? Far more knowledge results from exploring why a set of conditions exists than from simply accepting those conditions and committing them to memory. Asking why a state has the borders it does unlocks a history of human strugglesfar more history than this book can contain, though this book does aspire to unearth the keys.

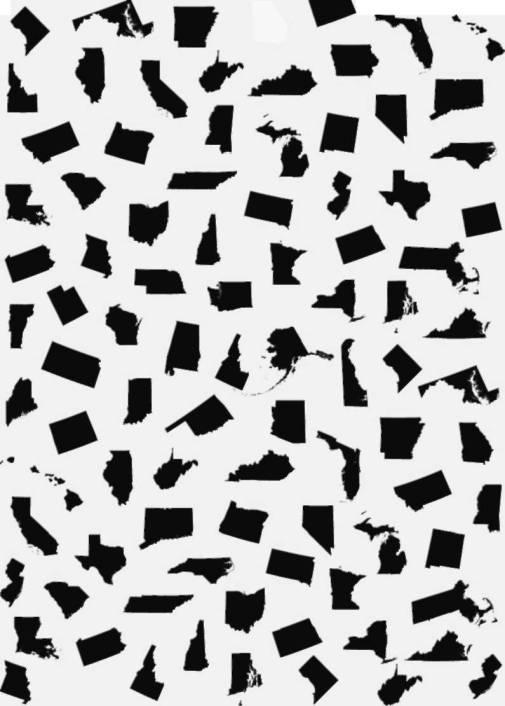

Consider for a moment the cluster of states composed of Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont. Why don't those states extend to their natural boundaries, the St. Lawrence River and the Atlantic Ocean? How come Canada got that land? (Figure 1)

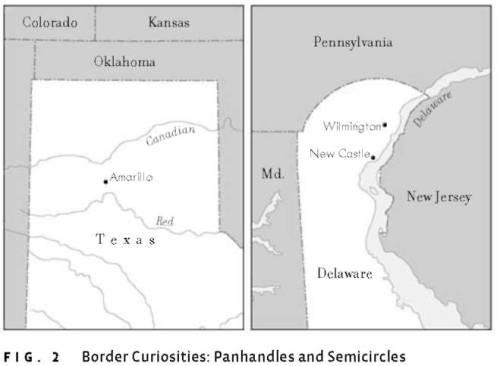

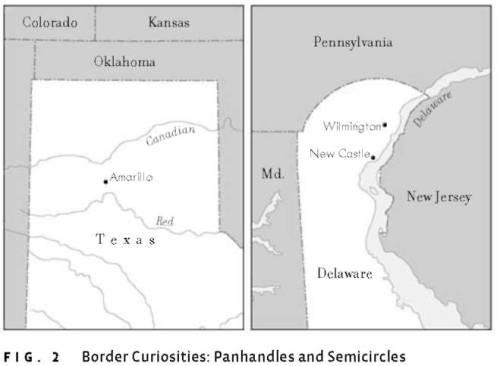

Why does Delaware have a semicircle for its northern border? What's at its center and why was it encircled? Why does Texas have that square part poking up? And why does the square part just miss connecting with Kansas, leaving that little Oklahoma panhandle in between? (Figure 2)

The more one looks at state borders, the more questions those borders generate. Why do the Carolinas and Dakotas have a North state and a

South state? Couldn't they get along? Why is there a West Virginia but not an East Virginia? And why does Michigan have a chunk of land that's so obviously part of Wisconsin? It's not even connected to the rest of Michigan! (Figure 3)

This book will provide those answers. State by state (along with the District of Columbia), the events that resulted in the location of each state's present borders will be identified.

A state border is both an official entrance and a hidden entrance. The official entrance is the legal threshold to a state. But its hidden entrance beckons us to the past. Here at the state line we can come in contact with struggles long forgotten and now overgrown by signs saying things like "Welcome to KansasPlease Drive Carefully."

Don't Skip This

You'll Just Have to Come Back Later

Many of our state borders are segments of borders that date from England's and, later, the United States' territorial acquisitions, and they can be identified by looking for lines that provide multistate borders.

The French and Indian War Border

The French and Indian War (1754-63) resulted in the oldest of these multistate boundaries. In this war, England and her American colonists began what became the dismantling of France's possessions in North America. With this victory, England added to her North American possessions all the land between the Ohio River and the Mississippi River. The boundaries of that war are still on the map today, for they provide borders for the states of Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, and Wisconsin. (Figure 4)

The division of this land acquired in the French and Indian War influenced virtually every state border that followed. After the Revolution, Congress had to decide how best to divide this region, known as the Northwest Territory, into states. Congress assigned Thomas Jefferson the task of studying this matter and in 1784 Jefferson issued a report to Congress in which he proposed that the region be divided into states

Next page