ALSO BY PORTER FOX

Deep: The Story of Skiing

and the Future of Snow

Copyright 2018 by Porter Fox

All rights reserved

First Edition

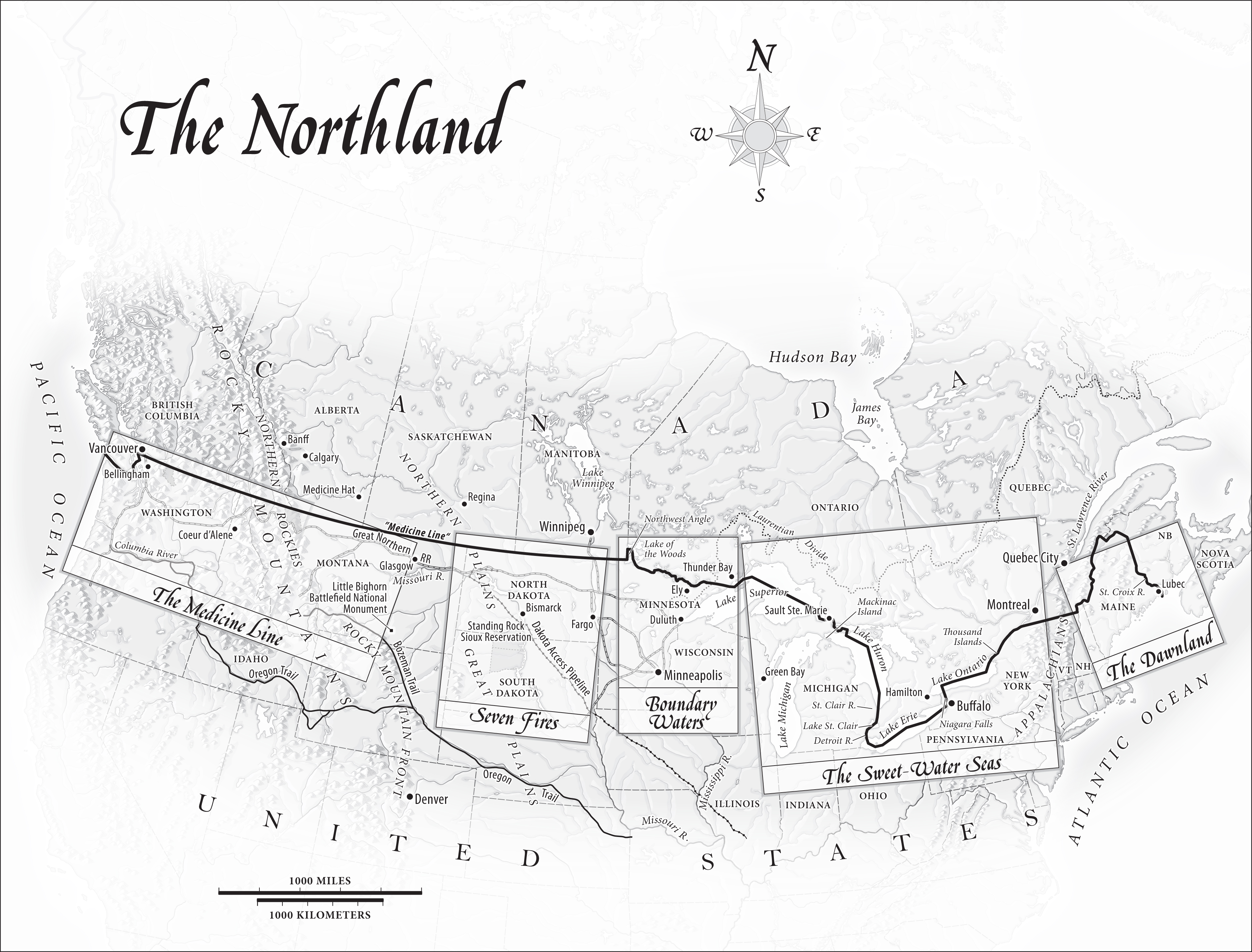

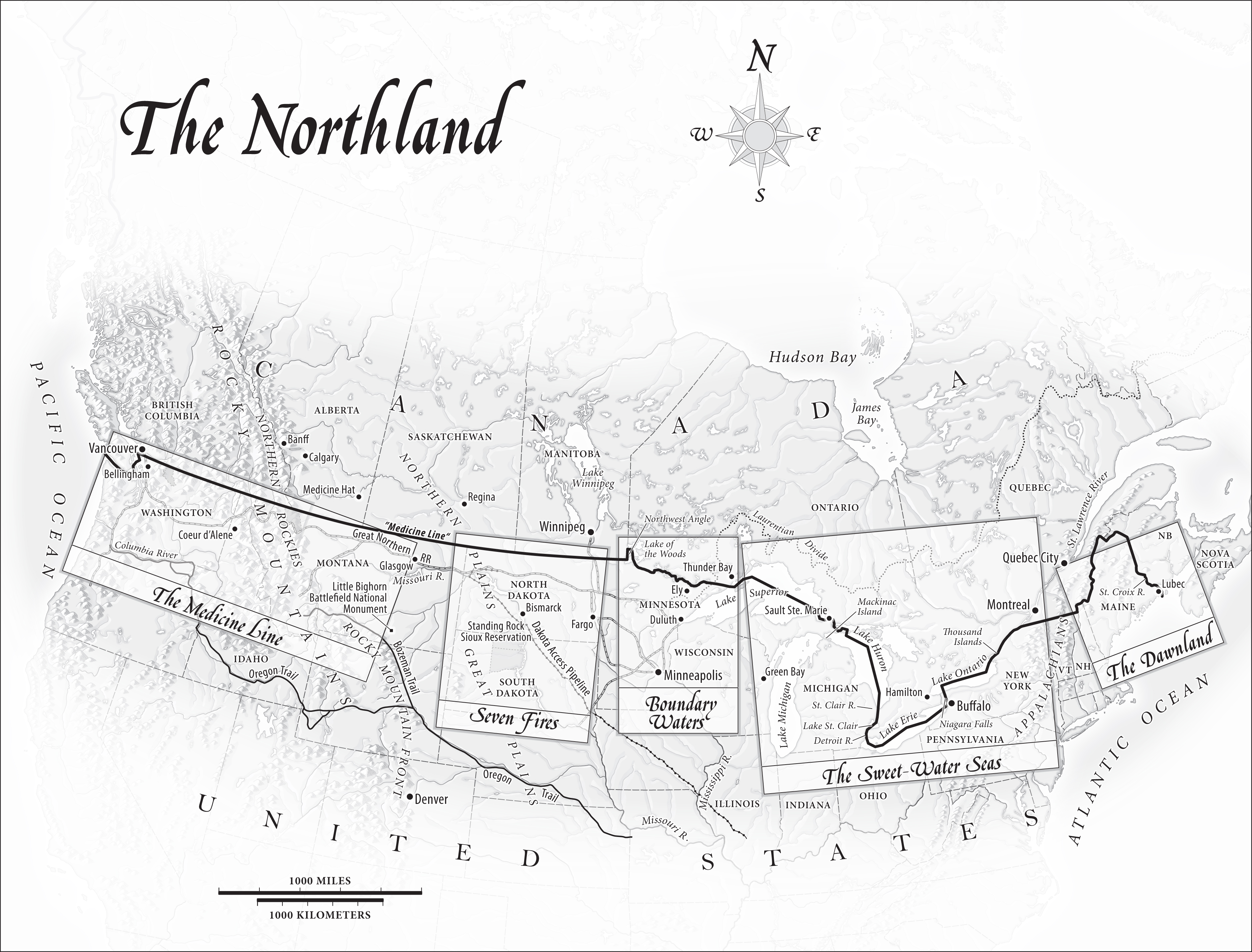

Maps by David Lindroth.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this

book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases,

please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at

specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Barbara Bachman

Production manager: Lauren Abbate

Jacket Design by Jim Tierney

The Library of Congress has cataloed the printed edition as follows:

Names: Fox, Porter, author

Title: Northland : a 4,000-mile journey along

Americas forgotten border / Porter Fox.

Description: First edition. | New York : W. W. Norton & Company,

[2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018002471 | ISBN 9780393248852 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Northern boundary of the United States

Description and travel. | Northern boundary of the United States

History. | Fox, PorterTravelNorthern boundary of the United

States. | Northeast boundary of the United StatesHistory. |

Northeast boundary of the United StatesDescription and travel.

Classification: LCC F551 .F75 2018 | DDC 974dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018002471

ISBN 978-0-393-24886-9 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

15 Carlisle Street, London W1D 3BS

for Sara

CONTENTS

N O ONE KNOWS WHERE AMERICAS NORTHERN BORDER BEGINS . It is somewhere near Machias Seal Island, twenty-five miles off Jonesport, Maine. Most know where it goes: six hundred miles around Maines panhandle; across New Hampshire, Vermont, and New York; west along the Saint Lawrence River; through four of the five Great Lakes; into Minnesotas Boundary Waters; and straight across North Dakota, Montana, Idaho, and Washington on the forty-ninth parallel.

On paper, the boundary looks like a discarded threadtwisted and kinked in parts, tight as a bowstring in others. Much of the line was drawn before modern surveying technology was invented, so it follows things you can see on a map: rivers, lakes, latitude, longitude. Where the boundary tracks a waterway, the rule is to follow the deep-water mark, making it look like a very drunk or very old man drew it freehandwhich, in some cases, is very close to the truth. The only indication that two of the worlds most powerful nations meet on these stretches is a procession of faded American and Canadian flags on either side, planted in yards, on porches, and on telephone poles.

The northern border looks like an accident in many places. It runs along the forty-fifth parallel straight through the Haskell Free Library and Opera House in Derby Line, Vermont. Near Cornwall, Ontario, it splits the Akwesasne Mohawk Indian reservation in half, and in Niagara it bisects the largest waterfall on the continent. Homes, businesses, families, golf courses, wood pulp factories, and a natural-gas plant straddle the line. Taverns were purposely built directly on the borderline during Prohibition to welcome Americans on one side and sell them booze on the other. Where the boundary follows the forty-ninth parallel in the West, it cuts straight through obstacles like valleys, watersheds, and eight-thousand-foot peaksnecessitating a chaotic system of rules and easements to determine sovereignty and access. Pan out 50,000 feet above the line and you see the shape of America. Zoom in and you recognize the timber yards, kettle lakes, tablelands, and two-lane asphalt roads of what locals call the northland.

Northlanders have little interest in the rest of the Union, and the rest of the Union has little interest in its northern fringe. There are other names for it: northern tier, Hi-Line, north country. Academics who study borders call either side of a new boundary where the line is vague and where the populations on both sides are still interconnected a borderland. As the border becomes more defined and enforced, the borderland evolves into bordered landswhere movement and commerce are restricted. What was once a singular region becomes two, and both sides develop individual identities, economies, and cultures. Land on either side of the US-Canada border exists somewhere between these two.

At 5,525 miles, including Alaska, the northern border is the longest international boundary in the world. Without Alaska, the 3,987-mile line capping the Lower 48 is the third-longest. Politicians, federal agents, pundits, and most Americans focus on the line with Mexico, even though its northern cousin is more than twice its length and many times more porous. The only known terrorists to cross overland into the US came from the north. Fifty-six billion dollars in smuggled drugs and ten thousand illegal aliens cross the US-Canada border every year. Two thousand agents watch the line. Nine times that number patrol the southern boundary. According to a 2010 Congressional Research Service report, US Customs and Border Protection maintains operational control over just sixty-nine miles of the northern border.

For two hundred years, the northern border was Americas principal boundary. The history of the continent played out along the line, chronologically from east to west: the Age of Discovery; the first colonies; the fishing, timber, and fur trades; the French and Indian Wars; the British Empire; the American Revolution; Lewis and Clarks Corps of Discovery; the War of 1812; the Indian Wars; and westward expansion.

An old friend once described the northland as a place that didnt change between the American Revolution and 1970. It is true. Bands of Scandinavians, Russians, French, Scottish, Dutch, and German Americansdescended from original settlersstill live there in an archipelago of ethnic islands. Some of the largest remaining American Indian tribesthe continents actual first settlerslive there too, most on exploited and tyrannized reservations. Auto maintenance, home maintenance, knowledge of weather, fishing, and hunting are essential skills because there is often no one there to do it for you. You can still put groceries on an account in the northland, run up a weekly tab at the bar, or take out your neighbors fence after one too many as long as you fix it within the month. The landscape there represents nature to people who visit for a long weekend and then race home. To northlanders, nature is not a thing you go see; it is the place you live.

It is not all quaint. There are problems like teen pregnancy, domestic violence, drugs, poverty, obesity, bigotry. Unless theres oil or gas to drill for, the economy is typically slow. In many places, there isnt much to do in the winter except work, watch TV, go to church, get drunk, get mad, or all of the above. The winter is long. It gets dark at four in the afternoon and stays that way until eight in the morning. It gets so cold that streetlights shine straight up through airborne frost instead of down. Towns smell of woodsmoke, and windstorms sweeping south from Canada make the forest groan.

When modern civilization finally arrived, the northland changed quickly. Silvery highways now cut across the backcountry, and high-voltage power lines slice through remote mountain passes. Tourists wearing safari vests have overrun centuries-old fishing and mill towns in the Northeast, while developers have made a killing selling luxury mountain homes in former western ranching and mining towns. Before September 11, 2001, half of the 119 border crossings between the US and Canada were unguarded at night. Since then, the Department of Homeland Security has increased the number of agents by 500 percent and installed sensors, security cameras, military-grade radar, and dronescutting off northland families, businesses, church congregations, hospitals, and Indian nations from their Canadian counterparts.

Next page