This is a sophisticated yet very readable analysis of Canadian-American relations. Well-grounded in borderlands literature, [Bootleggers and Borders] offers a nice balance of national histories intertwined with the importance of regional identities and cross-border ties in the Pacific Northwest.

Robert Campbell, dean of Arts and Sciences at Capilano University, Canada, and the author of Sit Down and Drink Your Beer: Regulating Vancouvers Beer Parlours, 1925

In the rapidly growing field of Canada-U.S. borderlands history, Moore has been, to date, the only scholar exploring the rich, fascinating, and completely unknown story of prohibition and bootlegging in the Pacific Northwest.

Sheila McManus, associate professor of history at the University of Lethbridge, Canada, and the author of The Line Which Separates: Race, Gender, and the Making of the Alberta-Montana Borderlands

Bootleggers and Borders

Bootleggers and Borders

The Paradox of Prohibition on a Canada-U.S. Borderland

Stephen T. Moore

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln and London

2014 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska.

Cover image courtesy City of Vancouver Archives.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Moore, Stephen T. (Stephen Timothy), 1969.

Bootleggers and borders: the paradox of prohibition on a Canada-U.S. borderland / Stephen T. Moore.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8032-5491-6 (hardback)

ISBN 978-0-8032-6784-8 (epub)

ISBN 978-0-8032-6785-5 (mobi)

ISBN 978-0-8032-6786-2 (pdf).

1. ProhibitionUnited States. 2. ProhibitionNorthwest, Pacific. 3. CanadaBoundariesUnited States. 4. United StatesBoundariesCanada. 5. United StatesRelationsCanada. 6. CanadaRelationsUnited States. 7. Northwest, PacificHistory20th century. I. Title.

HV 5089. M 76 2014

363.4'1097309042dc23

2014025093

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Contents

Photographs

Maps

The Natures of Border

Perhaps never was the borders ambiguity more propitious, and yet more problematic, than during the United States noble experiment with prohibition. For over a century, advocates of temperance reform had railed against the evils of liquor. Free of alcohol, they argued, society would be healthier physically, morally, and psychologically. Workers would be more productive; children would be protected from abusive fathers and wives from abusive husbands. By the end of the First World War, most Americans agreed. When the Eighteenth Amendment took effect in January 1920, no longer could Americans make, sell, transport, or import any intoxicating beverage that contained more than 0.5 percent alcohol. They could, however, legally drink it, and thus it was left to the amendments enforcement mechanism, the Volstead Act, to ensure that they did not have access to it.

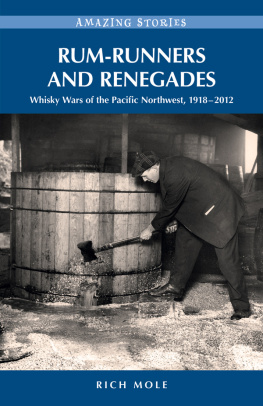

Predictably, from the Pacific to the Atlantic, American dollars promptly headed north and (usually) pure, Canadian whisky, south. Canadian distillers, brewers, export houses, rumrunners, and bootleggers were more than happy to assuage the parched throats of their American friends. In the Northwest, hundreds of yachts, steamers, and schooners ran liquor from Vancouvers Rum Row into the Puget Sound. Farther east, at Crowsnest Pass on the British ColumbiaAlberta border, McLaughlin Whiskey Sixes raced across the sometimes ill-defined border to supply speakeasies and roadhouses in Spokane, northern Idaho, and western Montana. However, what was a boon to the Canadian and British Columbian economies frustrated and exasperated American diplomats and enforcement officials, who sought from their Dominion counterparts help in stemming this illegal torrent of liquor. Between 1920 and 1933 no issue in Canadian-American relations proved more contentious or more intractable.

One might expect to find the reasons for this intractability in the letters carried in diplomatic pouches traveling between Ottawa and Washington DC . If there is any truth to Keenleysides observations about the border, then what does the border mean and what is special about the special relationship? How did these features of the Canadian-American relationship factor into prohibition?

This study contends that the root of the prohibition enforcement problem lay not so much in the diplomatic relations between Ottawa and Washington DC as in the less formal, but more common, everyday borderlands relations between Canadians and Americans generally. A major premise of a borderlands approach in the Canadian-American context is that North America runs more naturally north and south than east and west. People living near the border may pay allegiance to their respective sovereignties but, due to continental geography and shared history, they often have more in common with their counterparts north or south of the border. Along borders, especially in areas distant from the centers of national power, foreign relations operate according to different methods and rules and are managed by different actors, who hold different assumptions and cultural values.

Perhaps nowhere was this more evident historically than in the transnational Pacific Northwest. West of the Continental Divide, inhabitants of British Columbia, Washington, Oregon, Idaho, and western Montana had long interacted without the mediation of their respective sovereignties. Compared to the almost impenetrable natural border presented Exploring what it was about the nature of the Canadian-American relationship in the Far West that caused British Columbians to support cooperation at a much earlier stage is one purpose of this study.

At the same time, lest one be deluded into an unchecked notion of continentalismin the Northwest or elsewhereto argue that the border is sometimes an abstraction is not to argue that it is unimportant or without meaning. Especially to Canadians. With over 75 percent of its population living within one hundred miles of the boundary, Canada is a border nation. The border is a reality of virtually every Canadians daily life, whether he or she lives in Toronto or Vancouver, Halifax or Calgary. Beyond the ways it informs the Canadian national identity, the borders meaning helps explain the relationship between Canadians and Americans generally. It is central to that relationship.

The border is also important for a different reason. Although the casual observer may see or cross the border without recognizing its significance, academics too often see it as a definitive line. In so doing, they fail to make the valuable comparative discoveries the border offers. This commonality calls into question the notion of American exceptionalism, or at least it forces us to reframe it in a North American context.

Thus, examining the nature of the relationship between British Columbians and Americans during prohibition offers a window into the subtle but important differences in the way Canadians and Americans approach similar problems. While the purpose of this study is not to provide a detailed interpretive history of the prohibition movement in British Columbia, in Canada, or in the United States, the differences in their respective systems have much to say about the nature of the borderlands relationship. Moreover, these differences played a crucial role in the Canadian decision about whether to accommodate American pleas for enforcement assistance and they provided an alternative model for temperance once the noble experiment finally ended. It is for these reasons that British Columbia plays a central and, in some places, a dominant role in the narrative of this story.

Next page