CHAPTER

The Dawn of Dry BC

LIKE ALMOST EVERYONE ELSE IN Vancouver, Rogers Building barbers had been speculating on the upcoming 1916 election-day suffrage and prohibition referenda. But as scissors snipped and razors scraped inside the ornate emporium (the 18-chair facility with plate-glass mirrors and marble columns was much more than a mere barbershop), what dominated the conversation wasnt womens voting rights; it was liquor. While customers talked about prohibition, most barbers kept their ears open and mouths shut on dry and wet issues.

It made sense that many women were campaigning to end the making and selling of liquor. As Manitoba activist Nellie McClung had said, We women have had nothing to do with the liquor business except to pay the price. That price was paid daily in pain and pride inside thousands of homes as drunken husbands battered wives while children went hungry because Daddy drank his paycheque away in a saloon. In spite of that, men were the only ones eligible to vote on the fate of the BC governmentand liquor.

On September 14, 1916, men tossed Billy Bowsers scandalized Conservatives out and brought in Baptist Harlan Brewsters Liberals. Men decided to finally grant women the vote and, with a perverse blend of righteousness and patriotism, to outlaw saloons and the booze most enjoyed so much.

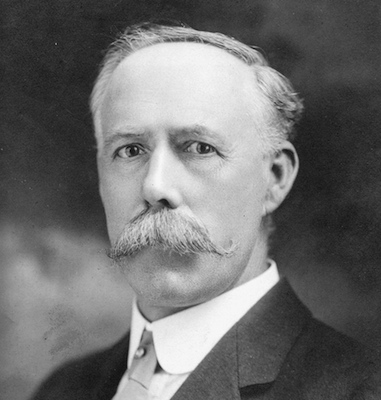

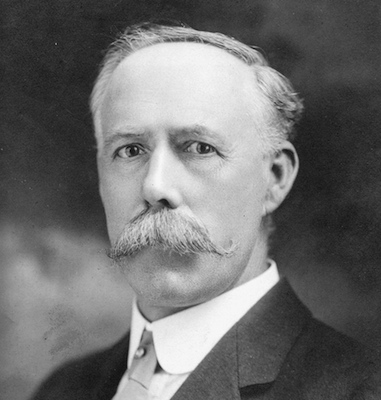

Rogers Building barbers had a personal connection with the struggle over drink that went beyond their taste for it. Jonathan Rogers, the builder and owner of the new downtown landmark, was one of prohibitions chief architects. Just as the completion of the majestic 10-storey building on the corner of Pender and Granville Streets had been a triumph for the pioneer Vancouver builder, so was the provinces Prohibition Act. Rogers enjoyed enormous influence as city alderman and chair of both the Board of Trade and Parks Board. Much of what wealthy Rogers and his wife Elizabeth did, including helping to found the Vancouver Art Gallery and Vancouver Symphony, they did to better the lives of others. Rogers likely regarded this as his civic duty. Moreover, as a good Methodist, Rogers regarded prohibition support as his moral and spiritual duty as well. Rogers helped organize the Peoples Prohibition Association (PPA) and was elected its first president. He then provided the PPA with free office space in his building. After a year of hard lobbying for a prohibition referendum, Rogers was rewarded with a dry vote.

Vancouver builder Jonathan Rogers was an ideal choice for president of BCs Peoples Prohibition Association. CITY OF VANCOUVER ARCHIVES AM54-S4

Walking into his Hastings Street office on BCs first dry morning, fellow Methodist and PPA member John Nelson was feeling mighty pleased, too. As the Vancouver Daily Worlds new owner and editor, Nelson had turned the newspaper into a mighty weapon of the whisky wars. On the eve of the referendum, Nelson urged his readers, Let your vote tomorrow be on the side of... the Mother and the Boy against the Saloon, the Brothel and the Distillers profits.

Nelson had emphasized the need for BC people to unite in the war effort. The war Nelson referred to was not the one being fought by the provinces wets and drys, but the one being fought in Flanders by over 40,000 uniformed BC men. Distillers and brewers, Nelson declared, had no business using valuable foodstuffs to manufacture intoxicants when British Columbians were fighting and dying in the mud of Passchendaele, Belgium. As workers abandoned farm fields for Flanders Fields, fears of food shortages loomed. The Canada Food Board advised BC residents to avoid wheat-based breakfast foods and to have at least one wheatless meal a day.

Every day, thousands scanned newspaper casualty lists for familiar names, hoping against hope they wouldnt find anyone they knew listed beneath the stark headings: WOUNDED, DIED OF WOUNDS, or KILLED IN ACTION. At last, through prohibition, families could do something to support and honour their husbands, fathers and sons serving overseas. The connection between the enjoyment of a pint of brew or bottle of rye and the carnage endured in the trenches seems tenuous now, but it didnt seem that way in 1916, when it was easyeven reassuringfor sorrowing families of the dead and wounded to forge a personal link between their bereavement and the battle against booze. As he sat behind his desk, John Nelson could take pride in his role in winning the whisky war in BCand, in doing so, winning that other war in Europe.

The saloons days were numbered. Bowing to prohibitionist pressure, the BC government had already outlawed 19th-century free-standing bars. By 1914, bars were found only inside hotels. Not long before, saloons had been the only site of culture, but now there were new theatres in major American and Canadian coastal cities, and the automobile made it easier for audiences to travel to see urban attractions. Many cities boasted libraries and even art galleries. Drinking establishmentsand even live-entertainment venuesfaced a new competitor, and by 1916, it was no passing fancy. The moving picture was here to stay.

People everywhere were talking about the new movie starsMary Pickford, Francis X. Bushman and racy Theda Bara. When fans werent paying a nickel to watch them, they were paying a dime to read about them in Motion Picture and Photoplay magazines. Movies became family entertainment when moms and dads took the kiddies to see cowboy shoot-em-ups starring Tom Mix and William S. Hart and the manic comedies of the Keystone Kops. No saloon ever enjoyed such a wide clientele.

British Columbia prohibitionists had been heartened by news from Washington communities that had gone dry through local option votes. During the 1912 state election campaign, prohibitionists had claimed A Dry Town Is Good for Bellingham and published facts and figures to prove it. Since Bellinghams 43 saloons had been boarded up the year before, the four-page pamphlet stated, The police force has been reduced fully one-third, and even then, find [sic] less to do than formerly. When saloons had been running the town, there were almost a thousand drunks arrested in 1910 alone, and homicides were of frequent occurrence. Only 169 drunks had slept it off in police cells during the first eight months of 1912, and in that period, there hadnt been one murder committed. Despite losing $48,000 in liquor revenue, Bellingham was now in better condition financially than before. The population was growing, bank deposits were increasing and the number of building permits had skyrocketed. Eleven saloons had done a roaring trade in Wenatchee, a town of 3,500. With the saloons gone, a former mayor reported the town had nearly doubled in size, and now boasted more civic development in this short space of time... than any city in the West.

As BC voters lined up at the polls, the news was even better. In Spokane, tax collection was easier, delinquency was down 50 percent and drunk arrests were down 67 percent. The Daily World reported that after just six months, Spokanes prohibition enforcement has done away with one-half to two-thirds of the poverty and crime in the city. Walla Wallas mayor announced drunkenness was down 80 percent. All this was a mixed blessing for State Highway Commissioner George F. Cotterill, however. Fewer state prison convicts meant he was forced to contract paid labourers to undertake road repairs.

When voters in smaller centres and rural areas tipped the balance and Washington State went dry, Spokane and Seattle had voted wet. However, once big-city folks experienced prohibitions initial benefits, most happily embraced prohibition, even though it cost their state the commerce of brewers, distillers and over a thousand saloons, and former employees lost their livelihoods. Some jobs went to wet San Francisco, the new location of Seattle Brewing and Malting (Rainier Beer), and its subsidiary, Independent Brewing Company. Brewers left behind were forced to make weak near-beer, sodas and other non-alcoholic drinks. Hotelmen and brewers lobbied hard for prohibition exemptions. One bill would have allowed the manufacture of beer sold directly to consumers, and another allowed the sales and consumption inside hotels. Elections in 1916 gave a solid majority the opportunity to vote no, defeating both bills.