Bootleggers and Beer Barons of the Prohibition Era

J. Anne Funderburg

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-1619-3

2014 J. Anne Funderburg. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

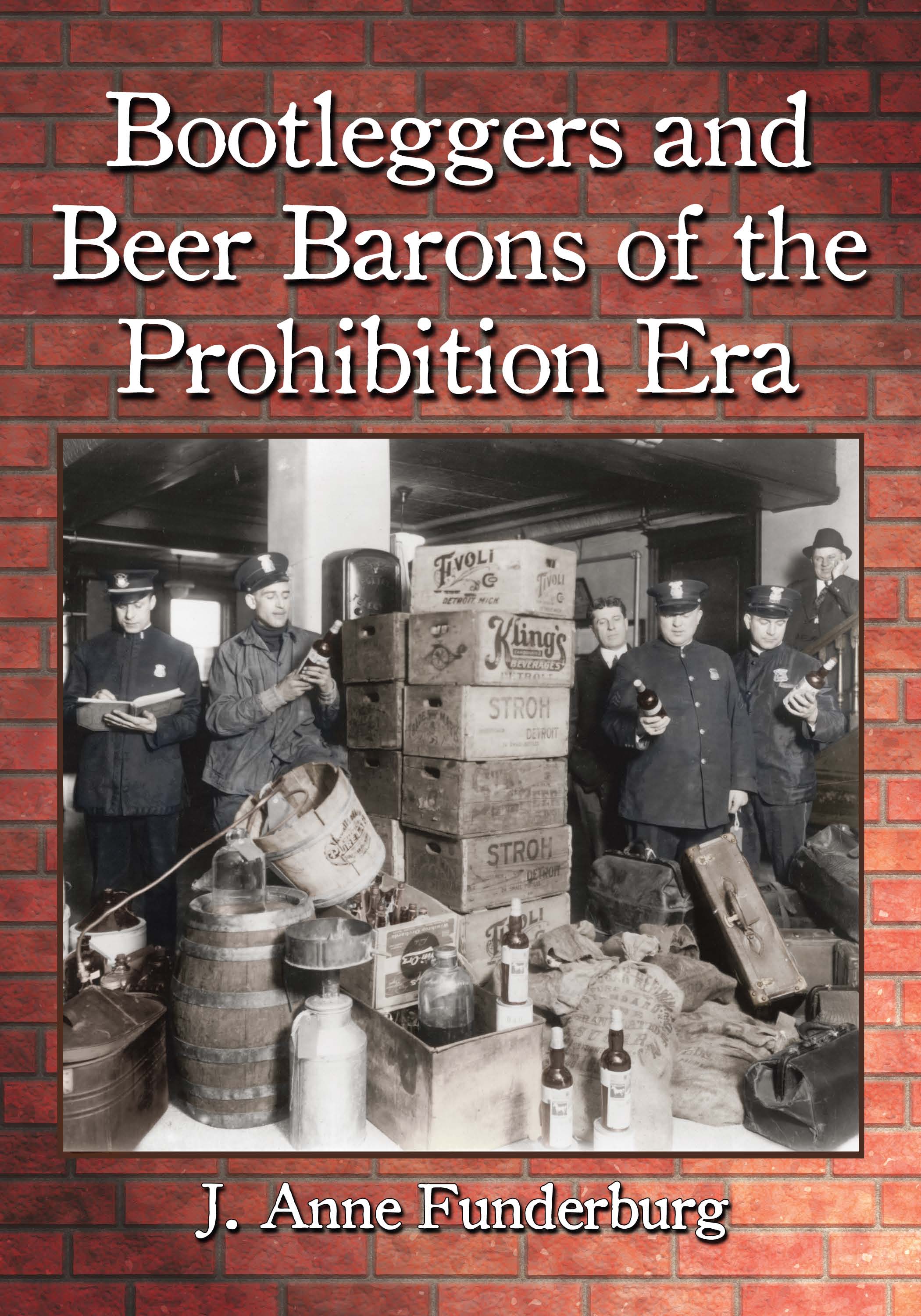

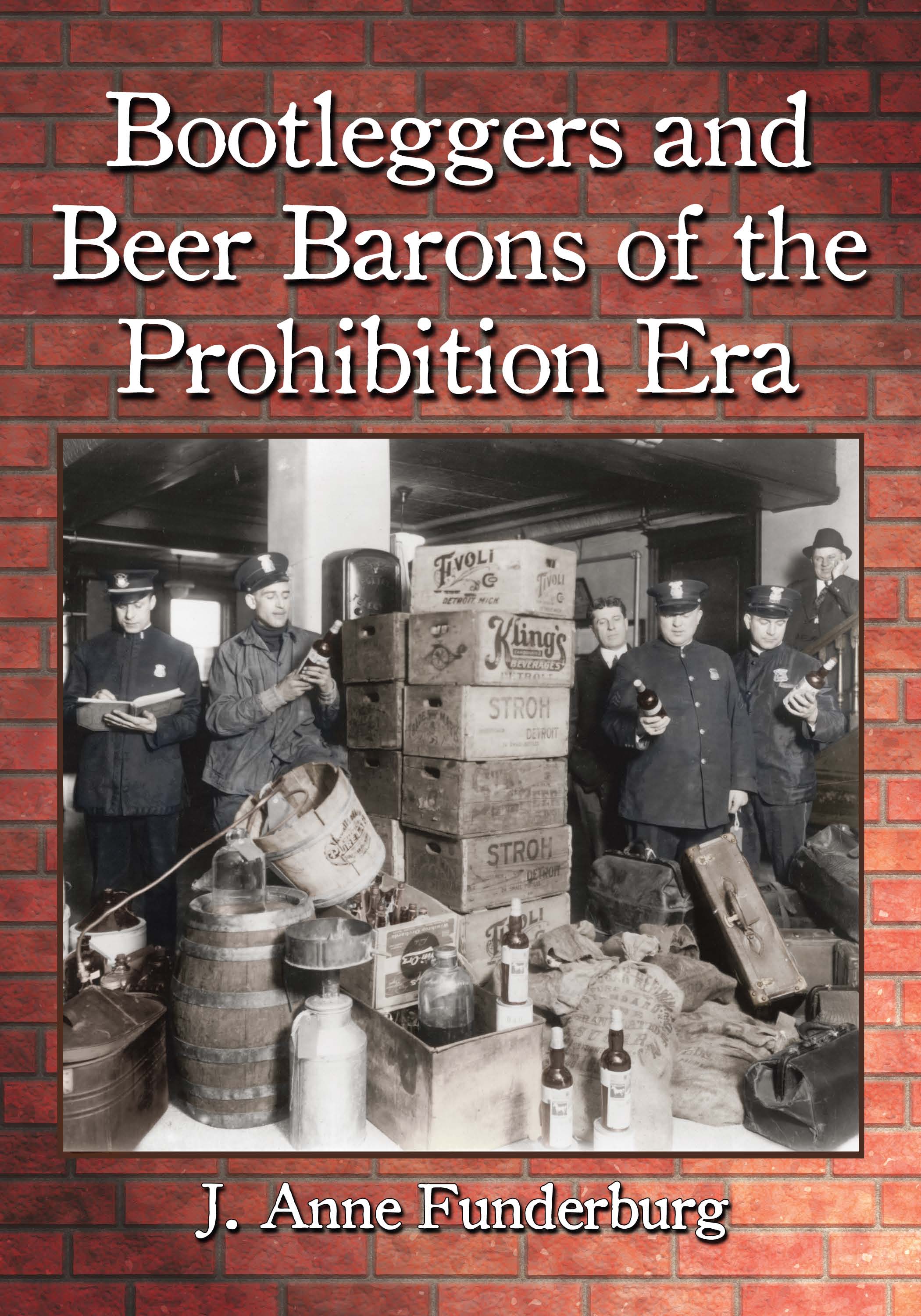

On the cover: police confiscating alcohol during Prohibition 1920-1933 (Photofest)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

To Murry, my sounding board,

touchstone, and soul mate

Preface

The enactment of Prohibition unleashed a massive crime wave from coast to coast. Millions of Americans broke the Volstead law and felt no remorse about it. The central player in this criminal plague was the bootlegger who delivered booze to the marketplace. He or she worked in an industry ruled by guns rather than government regulations. Brutal, ruthless men rose to the top of the illegal liquor traffic. Through the media, the public came to know these men who called the shots in the underworld. Pop culture turned them into famous antiheroes admired by drinkers and hated by Prohibitionists.

Early in the Volstead Era a stereotype emerged of the bootlegger as an urban mobster who packed heat and reveled in shootouts with lawmen and rival gangsters. The medias stereotypical beer baron had a strong ethnic identity and was an immigrant or first-generation American. In reality, many bootleggers fit this mold, but many did not. In some areas the typical bootlegger belonged to an old-stock family with deep roots in American soil. He or she valued individualism, liked small-town life, and had no desire to belong to an urban-style gang. Yet the public image of the Volstead lawbreaker has been rather narrowly defined, with the urban mob boss dominating in pop culture.

To provide a balanced view of Volstead crime, Bootleggers and Beer Barons of the Prohibition Era looks at the business of bootlegging in multiple locations, spanning the country from New York City to Seattle, Washington. The book tells the stories of rural and small-town hooch haulers as well as urban liquor lords. The nationwide survey reveals that the members of the bootlegging fraternity shared commonalities, but some aspects of the business were unique to certain areas. Each gin jogger was an individual with a distinctive personality, although a few basic goals and traits may be attributed to the vast majority of bootleggers. The liquor runners lived dangerous lives outside the mainstream, supplying an illegal commodity to average Americans. They were criminals aided and abetted by corrupt lawmen, malfeasant officials, straw men, mob lawyers, moonshiners, alky cookers, forgers, counterfeiters, andmost of allconsumers who thirsted for something stronger than lemonade.

A NOTE ON SPELLING:Whisky and whiskey are variant spellings of the same word. Traditionally, whisky was the preferred spelling in British and Canadian English while American English had no firm rule. In some publications, whisky refers to the Scotch and Canadian varieties while whiskey is used for American and Irish products. For consistency, this book uses whiskey in all contexts.

Part I

The Volstead Law: King Alcohol Dethroned

1

Satans Best Friend, Gods Worst Enemy

The American republic has solemnly placed itself on record as prohibiting the greatest enemy of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. There are not enough society creampuffs, political grafters, underworld gunmen, or social morons in the land to prevent the fulfillment of that prohibition.Wayne Wheeler, General Counsel, Anti-Saloon League of America

January 17, 1920, was Al Capones twenty-first birthday, but he didnt celebrate with a legal drink at the corner saloon. The Volstead Act took effect at 12:01 a.m., knocking King Alcohol off his throne and sending him into exile. The activists behind Prohibition knew with absolute certainty that the new dry law would improve society in every way. The law would turn the habitual drunkard into a sober, hardworking, devoted family man. Instead of wasting his paycheck on booze, the reformed sot would spend his wages wisely. He would pay his debts and open a savings account. His children would have shoes and warm winter coats. He would enjoy wholesome fun with his family, and America would become a land of innocent pleasures. Clean, sober Christian fellowship would provide all the social life anybody could possibly want.

Al Capones instincts told him the drys were all wet. Despite his youth, he already had a fondness for what he called the light pleasuresdrinking, gambling, and visiting brothels. He didnt plan to give up his fun, and he didnt expect other drinkers to become teetotalers just because a bunch of meddling do-gooders passed a law. Growing up poor in a crime-ridden tenement district, Capone had learned to grab what he could take and fight for what he wanted. He had street smarts, greedy ambition, gangland connections, and few scruples to slow him down. For him, and his ilk, Prohibition would open the door to riches, power, and infamy.

The dry forces had fought a long, arduous war against Demon Rum. For decades, the liquor issue had divided the United States into two camps: the drys who demanded alcohol abstinence, enforced by law if necessary, and the wets who believed that drinking should be a personal choice. The middle class, church folk, nativists, farmers, and small-town residents formed the backbone of the dry faction. Urbanites, ethnic minorities, immigrants, and blue-collar workers generally favored little or no regulation of the liquor traffic. Protestants tended to support strict liquor control laws, while a majority of Catholics and Jews viewed drinking as a personal decision.

Efforts to restrict the liquor traffic dated back to Colonial America, but the dry movement didnt become a political juggernaut until the late nineteenth century. Before the Civil War, most dry leaders were temperance advocates who preached moderation, not total abstinence. After the war, the dry movement evolved in a more militant direction. Turning all Americans into teetotalers became the goal of the postwar cold water coalition. Social conservatives, religious crusaders, and progressive reformers banded together because they all believed that banishing King Alcohol would greatly benefit the nation.

The nativist social conservatives wanted to preserve what they believed to be true American values and the American way of life. Religious crusaders wanted to save the drunkards soul and foster Christian family life. Progressive reformers wanted to improve society by eradicating vice, crime, and corruption. They formed countless investigative committees, issued tons of reports, and sought to pass legislation that would further their vision of a better tomorrow. Of course, many dry activists had overlapping goals; a religious crusader could also be a progressive reformer, for example.

The dry movement was tinged with xenophobia and racism, especially in the nativist faction. Bigots told lurid stories about drunken Negroes who ran amok and committed heinous acts, like cannibalism or the nameless crime (AKA rape). An editorial in a Nashville, Tennessee, newspaper singled out the Negro problem as the most urgent reason for closing the saloons. The Negro, fairly docile and industrious, becomes, when filled with liquor, turbulent and dangerous and a menace to life, property, and the repose of the community, warned the paper. An Illinois dry leader called the grogshop the Negros center of power. She declared, Better whiskey and more of it is the rallying cry of great dark-faced mobs.

Next page