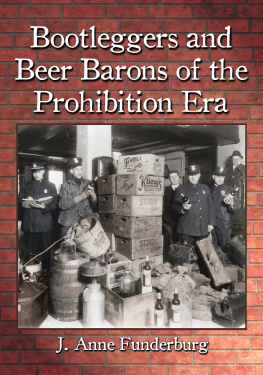

Also by J. ANNE FUNDERBURG

Bootleggers and Beer Barons of the Prohibition Era

(McFarland, 2014)

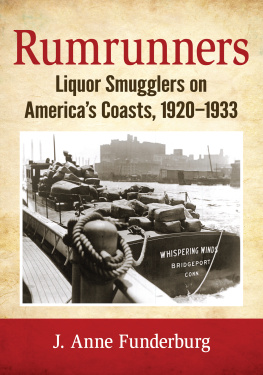

Rumrunners

Liquor Smugglers on Americas Coasts, 19201933

J. ANNE FUNDERBURG

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Jefferson, North Carolina

e-ISBN: 978-1-4766-2670-3

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

BRITISH LIBRARY CATALOGUING DATA ARE AVAILABLE

2016 J. Anne Funderburg. All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

On the cover: Burlocks filled with bottles of liquor are visible on the deck of a contact boat, Whispering Winds. The Coast Guard confiscated this boat and added it to the Dry Navy (National Archives and Records Administration)

McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers

Box 611, Jefferson, North Carolina 28640

www.mcfarlandpub.com

Preface

The present work is the first accurate, comprehensive history of liquor smuggling on the high seas during the Volstead Era (19201933). Previous histories of the war between the rumrunners and the Dry Navy have relied heavily on anecdotes and personal recollections. This book is based on legal records, scholarly sources, newspaper archives, and the U.S. Coast Guard files at the National Archives and Records Administration.

In general, previous histories of rumrunning have focused on one geographic area. This book examines liquor smuggling along the entire coastline of the United States, spotlighting the busiest centers: New York, New Jersey, Florida, and California. The author chronicles Americas most daring rumrunners, including two fascinating but little known women, Gertrude Lythgoe and Edith Stevens.

Unlike previous histories, Rumrunners presents a balanced view of the conflict, looking at the losses and victories on both sides. The author covers both rumrunners and the Coast Guardsmen ordered to enforce Volstead. She looks at corruption in the Coast Guard but also gives accounts of honest Guardsmen who risked their lives to capture liquor smugglers.

The author analyzes both the domestic and international legal issues involved in confiscating ships and liquor cargos. She also discusses the foreign policy repercussions of Volstead enforcement, particularly the disputes spawned by the Coast Guards seizure of Canadian ships with British registry.

1

Rum Row

Mother Ships and Mosquito Boats

A romantic aura surrounded rumrunners during Prohibitions early years. They were renegades, swashbucklers, adventurers. They sailed the high seas, outwitting hijackers, dodging the Coast Guard, and delivering the good stuff from exotic ports of call. They were daring, rugged individualists defying a law hated by millions of Americans. When the rum smuggler brought his liquor cargo ashore, he struck a blow for personal liberty and the right to choose gin instead of ginger ale. Drinkers admired him. Prohibitionists despised him.

The rumrunner took serious risks on every voyage. Any rumrunning trip could end violently with a hijacking, a shipwreck, or a shootout with the Coast Guard. Rumrunners live close to danger and are not unfamiliar with the image of death, a newsman wrote. Rumrunners chose to dare death because they loved the thrills and the money. Rum-running is a game that may be a profitable game beyond any dream of fisherman or merchant skipper. They have elected to take a chance.

The booze buccaneer was the true heir, not only of the old-time Indian fighters and train robbers, but also of the tough and barnacled deep-water sailors, now no more, wrote H.L. Mencken. He likened the rumrunners to the Minutemen who fought for freedom in the American Revolution. Liberty, driven from the land by the Methodist White Terror, has been given a refuge by the hardy boys of the Rum Fleet. In their bleak and lonely exile, they cherish her and keep her alive.

Mencken, who loathed Prohibition, demonized the Methodist Church because it had played a pivotal role in the U.S. temperance movement. Early Methodist leaders, including John Wesley and Francis Asbury, had preached the importance of moderation in drinking. Puritan divines Cotton and Increase Mather and Congregational minister Lyman Beecher were among the first public figures to warn Americans about alcohol abuse. Quaker and Presbyterian leaders also endorsed sobriety as a virtue for individuals and for society as a whole. Nevertheless, Americans were slow to grasp the concept of substance abuse because they viewed alcohol as a blessing. In fact, alcoholic beverages were commonly called Gods good creatures.

The American colonists used fermentation and distillation to preserve fruits, grains, and vegetables because alcoholic beverages had a long shelf life. Unlike fresh foods, potent potables didnt rot. The colonists used alcohol as medicine and relied on it to treat virtually every illness that plagued mankind. Whether sick or healthy, adults drank alcohol, often in the form of beer or hard cider, from breakfast to bedtime. In many families, even young children routinely drank beverages with low alcohol content.

In the early nineteenth century, the perception of alcohol as a blessing faded as drinking habits changed. Distilled spirits displaced Americas traditional fermented beverages with low alcohol content, such as apple cider. Ardent spirits, especially rum and corn whiskey, became immensely popular because they were cheap and potent. Americans drank to excess more often, and drunkenness had a negative impact on society. Heavy drinking often played a role in crime, violence, and domestic abuse.

To combat alcohol abuse, religious and civic leaders started temperance groups to encourage moderation and sobriety. For the most part, the dry leaders didnt demand total abstinence from alcohol, but they called for responsible drinking to reduce drunkenness and the evils associated with it. The temperance societies formed national organizations and persuaded millions of Americans to join the dry crusade.

Before the Civil War several state governments enacted laws that prohibited the manufacture and sale of alcoholic beverages. These laws had little impact because bootleggers and illegal saloons sold liquor in the dry jurisdictions. During the Civil War the temperance movement lost its momentum as the nation dealt with crucial problems that threatened the Union. After the war, Americans focused on rebuilding the nation, and the temperance activists slowly regrouped.

In the 1870s church women formed the Womans Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) to rid America of drunkenness and the ills that accompanied it. Women didnt have the right to vote, which limited their impact on elections and legislation. Hence, the ladies crusade emphasized moral suasion, anti-alcohol education, and wholesome activities for young people. In 1893 male activists founded the Anti-Saloon League (ASL) and set out to harness the political power of the dry bloc. The ASL focused on mobilizing dry voters to elect officials who would enact prohibitory laws at all levels, from local to federal.

The ASL and WCTU led an informal alliance of anti-alcohol groups, often called the Cold Water Coalition. Dry activists usually had more than one reason for joining the crusade; the most common motivations were religion, progressive reform, and/or nativism. Many devout Christians believed that drunkenness was the gateway sin on the road to hell. They wanted to save souls by keeping everybody sober and focused on the Gospel. Progressive reformers viewed alcohol as a basic cause of violence, crime, broken homes, prostitution, poverty, and other social ills. They believed that abolishing the saloon and passing strict liquor laws would greatly improve the quality of life for individual families and for the community as a whole.

Next page