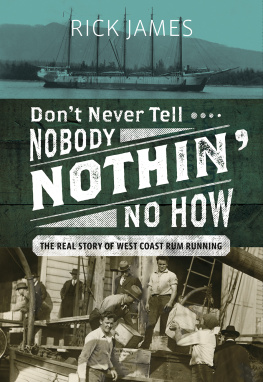

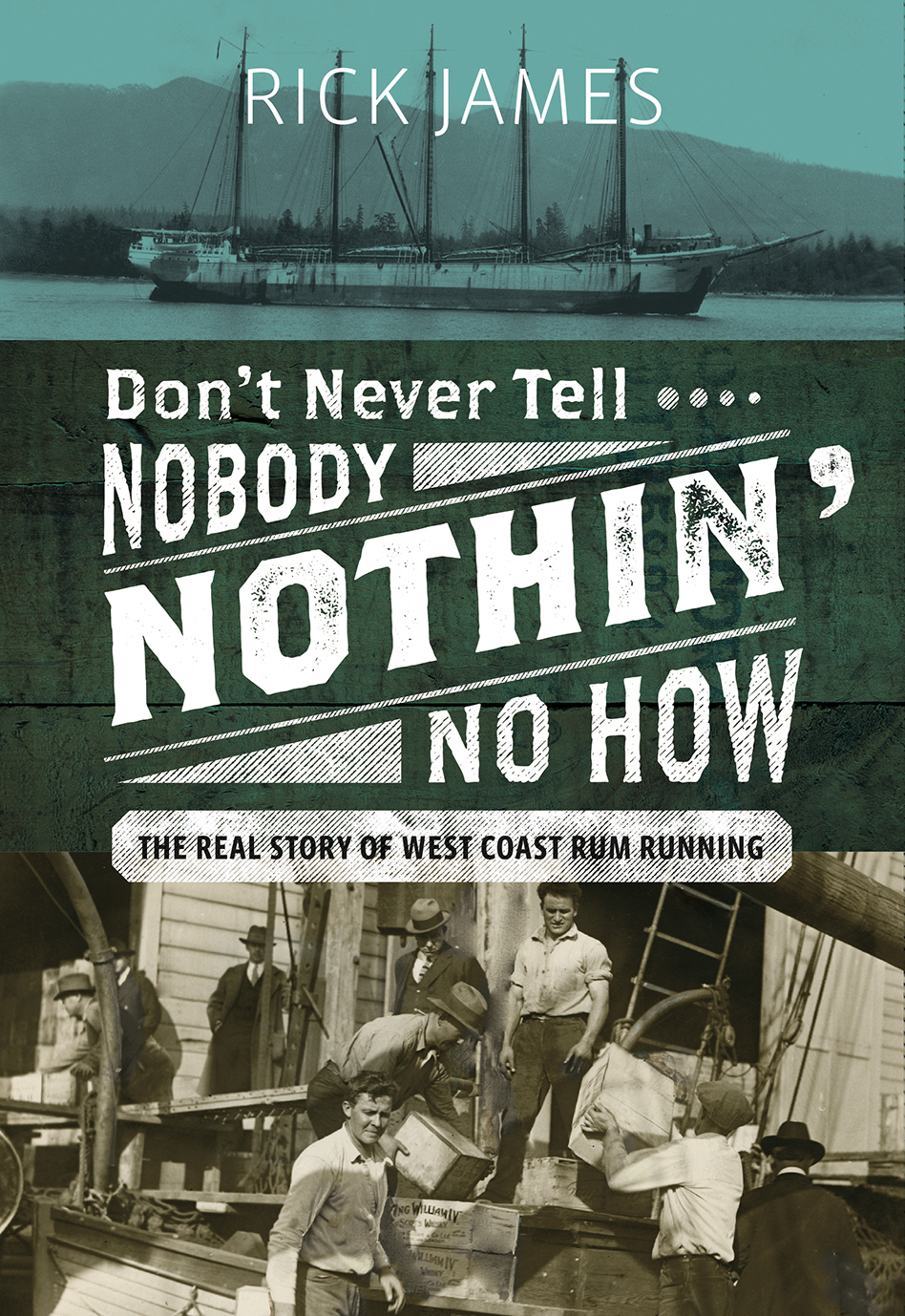

Dont Never Tell Nobody Nothin No How

Rick James

Copyright 2018 Rick James

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, .

Harbour Publishing Co. Ltd.

P.O. Box 219, Madeira Park, BC , V 0 N 2 H 0

www.harbourpublishing.com

Edited by Peter Robson

Indexed by Emma Skagen

Jacket design by Anna Comfort OKeeffe

Text design by Shed Simas / Ona Design

Maps by Roger Handling

Printed and bound in Canada

Printed on FSC -certified paper

Harbour Publishing Co. Ltd. acknowledges the support of the Canada Council for the Arts, which last year invested $ 153 million to bring the arts to Canadians throughout the country. We also gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Government of Canada and from the Province of British Columbia through the BC Arts Council and the Book Publishing Tax Credit.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

James, Rick, 1947-, author

Don't never tell nobody nothin' no how : the real story of West Coast rum running / Rick James.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-55017-841-8 (hardcover).-- ISBN 978-1-55017-842-5 ( HTML )

1. Alcohol trafficking--British Columbia--Pacific Coast--History--20th century. 2. Prohibition--British Columbia--Pacific Coast--History--20th century. I. Title. II . Title: Do not never tell nobody nothing no how.

HV 5091. C 3 J 36 2018 364.1'3361097111 C 2018-903485-8

C 2018-903486-6

The Two Jims, wherever they are

Table of Contents

Introduction

Dont Never Tell Nobody Nothin No How

Looking back, it seems that I was destined to write about West Coast rum running. My dad, Dick James, was born in the Shetland Islands to Richard Pascoe James, a Cornish tin miner, and Ruby (ne Scott). Grannys family had made a living from the sea for generations and her grandfather and father, both named Peter, supplemented their hardscrabble existence as cod fishermen and whalers by smuggling tobacco and spirits. As it was, smuggling was never considered a crime or a sin by Shetlanders who struggled to get by on the isolated Scottish archipelago off the far end of the North Sea.

William Smith, a merchant and fish curer in the port village of Sandwick, who crewed with Rubys grandfather on the packet boat Rising Sun in 1891, recalled that Scott Jr. (Rubys father), said his father didnt really care for strong drink and so seldom got into positions that he could not extricate himself from. At the time Scott Sr. was running Rising Sun as a Cooper, or smuggling vessel. They would fill the hold with tobacco and spirits at ports in Holland and Germany and then run the cargo across to the Yarmouth, Hull and Grimsby fishing fleets where they carried on a brisk trade. Prior to Rising Sun, Scott Sr. ran Martha of Geestemnde with son Peter as mate. The Scotts acquired the German boat after she was caught smuggling off the Shetland Islands coast in 1886. After they pleaded guilty, master and owner were fined twenty pounds sterling or the alternative of serving thirty days imprisonment, while the three-man crew was fined five pounds each or twenty days in prison. Boat and cargo were subsequently seized and the boat ended up in the hands of the Scott boys.

Four generations later, the appeal of earning a living smuggling came to the fore in my own life. After graduating from Oak Bay High School in Victoria in the mid-1960s, smoking pot and hash was a recreational activity the crowd I hung out with often indulged in. We were in our late teens and early twenties, still trying to sort out how to navigate the adult world and preoccupied with how to get by or, at least, earn a half-decent income without resigning ourselves to a boring, humdrum job around town. Some who were adventurous enough headed up island to work in the woods setting chokers or landed jobs on trollers as deckhands. But living on the south end of Vancouver Island, where its only a few short miles across Haro Strait into United States waters and the San Juan Islands, there was another, riskier enterprise that offered the potential of a very lucrative reward. And a few of my pals were crazy enough to try it.

It only required finding a reasonably reliable boat with a good, fast engine and making a run across Haro Strait, preferably during a dark and overcast night, to pick up an order of a few pounds of product on the other side of the line. Of course, it was all highly illegal but thats how economics works: the higher the risk, especially with the selling of a banned and illegal substance, the greater the potential for an exceptional return on ones investment. The idea seemed so very straightforward when presented by a couple of my colleagues who were always pressuring me to take part in one of their sketchy money-making schemes.

Forty years later, one old friend finally opened up and divulged his secret to success. To begin with, since my crowd was mostly from long-time Victoria families, they either kept their boats at the Oak Bay Marina or trailered them down to the Cattle Point boat launch. Then on a good dark night with no moon in the sky, they would race across into Washington state waters to Deadman Bay on San Juan Island. This particular location on the chart was Vancouver Island drug runners preferred spot for making a pickup. First of all, this rather quiet and isolated bay lies just outside of San Juan Islands Lime Kiln Point State Park, and Lime Kiln Lighthouse serves as an excellent navigational aid for those running across the strait from Victoria. Also, Deadman Bay is reasonably well sheltered with a nice moderately sloped beach for pulling a small boat up on. But not only that, the islands West Side road comes almost right down to the water in the bay. Here, their Canadian partners in the venture car or truck would arrive after picking up some pot in Oregon, so-called cheap Mexican shit selling for around seventy to seventy-five dollars a pound back in those days. After the transport vehicle arrived down at Deadman Bay, the product was discharged and loaded into the boat, which then raced off across the strait into Canadian waters. Once the weed hit the streets of Victoria, the dealers were able to sell it for a hundred and twenty dollars a pound.

Another reason why Deadman Bay worked so well was that there was little in the way of law enforcement on San Juan Island in those halcyon days of the 1960s and 1970s. As my old bud pointed out, there was virtually no US Coast Guard around in those waters, and he didnt recall there ever being any border protection service, drug enforcement or customs agents about, especially on the Haro Strait side of the island. The only police presence there at the time was the local sheriffs office. Even so, a number of the crowd I hung out with didnt have the sense to know when to call it quits. While many of us got into psychedelics, some took it a little too far and not only got into coke but even proceeded into far worse intoxicants like speed (methedrine) and junk (heroin) and bore the consequences. Then there were those who got busted for possession or, worse yet, running drugs into the country, and ended up with a record or even jail time. Even though many were actually quite bright and charming individuals, once they spent time behind bars they were never quite the same.