BERKLEY

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014

Copyright 2018 by Ambrose, Inc.

Penguin Random House supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for every reader.

BERKLEY is a registered trademark and the B colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Ambrose, Hugh, author. | Schuttler, John, author.

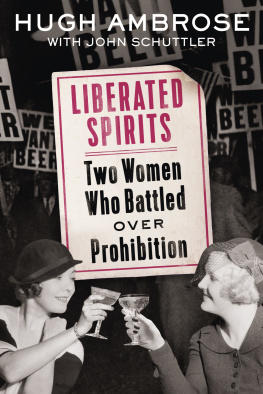

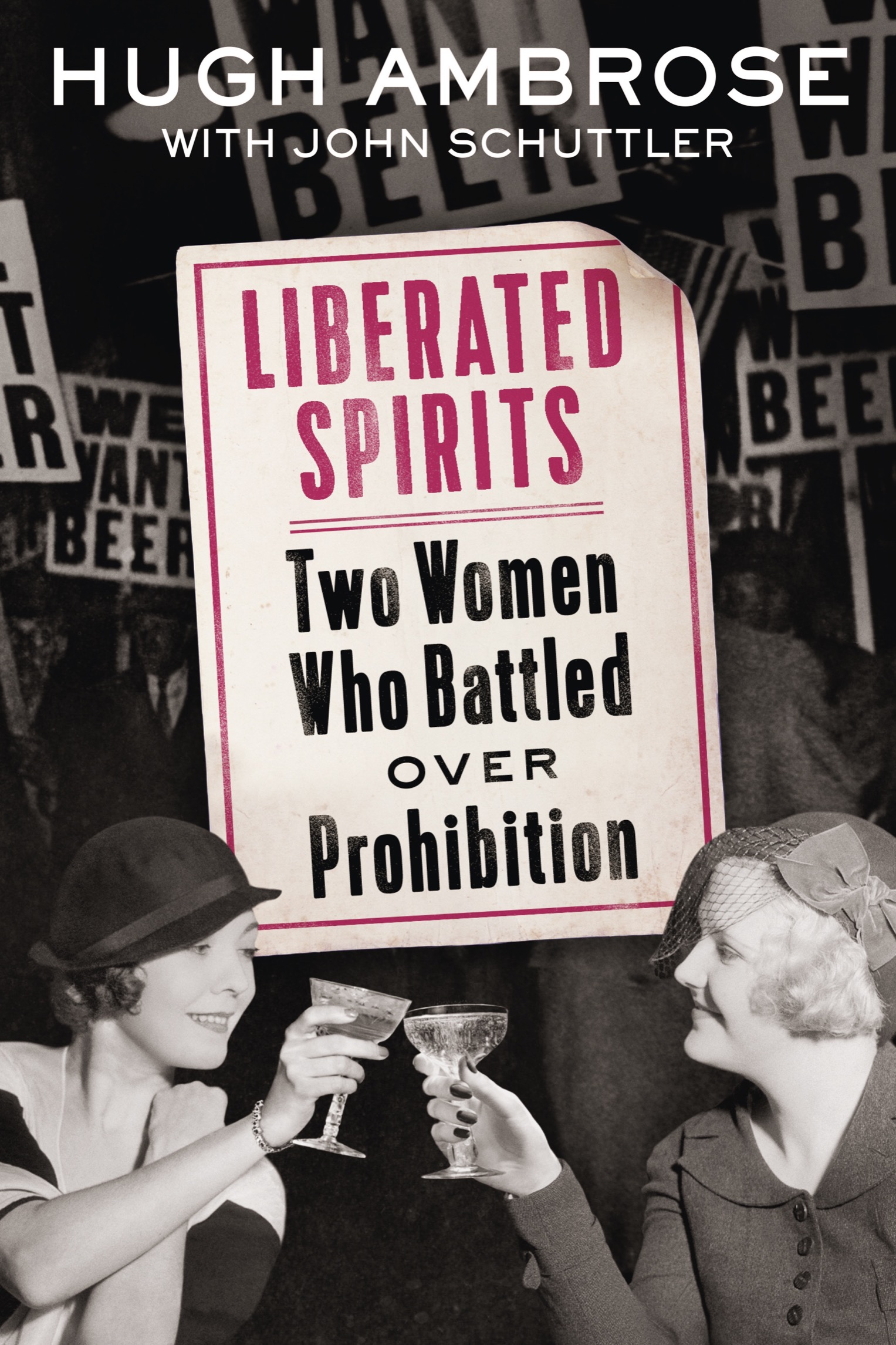

Title: Liberated spirits: two women who battled over Prohibition/Hugh Ambrose, with John Schuttler.

Description: First edition. | New York: Berkley, [2018]

Identifiers: LCCN 2017052487 | ISBN 9780451414649 | ISBN 9780698183636 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Willebrandt, Mabel Walker, 18891963. | Davis, Dwight, Mrs., 18871955. | ProhibitionUnited States. | WomenPolitical activityUnited StatesHistory20th century. | United StatesHistory19191933.

Classification: LCC HV5089.A576 2018 | DDC 344.7305/41dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017052487

First Edition: October 2018

Jacket photos: image of women courtesy of Old Visuals/Alamy Stock Photo; background image of demonstrators courtesy of Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo/Alamy Stock Photo

Jacket design by Emily Osborne and Colleen Reinhart

While the authors have made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, Internet addresses and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the authors assume any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Version_1

For Ande, Elsie, and Brody

For ever

Introduction

The rumrunner Roy Olmstead had the key assets to succeed: a talent for inspiring confidence in business partners for a venture in which no contract or agreement carried the force of law; the ability to manage an organization, a skill cultivated in his years rising through the ranks of the police force; and all the pluck and entrepreneurship of a born capitalist. This March evening found Olmstead and his associates exercising all their talents to bring in a large shipment of choice liquors and wines.

Just after one oclock on Monday morning, the bootleggers turned left, off the paved road, and drove down the steep hill to the water. Their carsrear seats removed to make room for the bottles, the cargo space supported by heavy-duty springs, the cars engines tuned for maximum powercould not fit into the narrow roadway near the dock, so they stopped in a line and waited. Olmstead had one of his men begin flashing a light periodically, facing westward out into Puget Sound. In less than an hour, the engines of the Jervis Island could be heard approaching. With enough cargo space to convey nearly eleven hundred cases from Victoria, Canada, across the Strait of Juan de Fuca, and down Puget Sound, Roys wooden-hulled boat had not been crafted for speedit couldnt even make ten knotsbut her stout frame handled the job in workmanlike fashion. As soon as she was tied to the pier, the unloading began.

Roy and Tom watched as their foreman, waving an electric flashlight and hollering profusely, directed the process of toting the cases from the boat and up to the waiting cars, sending each loaded automobile on its way and waving in the next. Satisfied with the arrangements, his own car loaded, Roy drove away up the hill, only to find a barricade of logs at the apex. Men brandishing gunsthieves or cops, he did not knowordered him to stop. As they neared his car, Roy spotted a way around and gunned the engine. Shots from their pistols did the men no good as he swerved back onto the dirt road, eventually picking up the pavement and heading south at full speed, surely wondering whether the gunmen were stealing his liquor or arresting his men, who had been instructed simply to turn over the goods if waylaid by hijackers. If the ambushers proved to be revenuers (agents of the federal Internal Revenue Bureau), or former revenuers recruited to be members of the brand-new Prohibition Unit, he had a different set of problems. In more than a century of chasing down moonshiners and others not in compliance with government liquor-tax policy, revenuers had built a reputation for unpredictability, some being virulent Prohibitionists smashing stills and bottles, others willing to take a bribe to turn a blind eye. It was unclear how they would handle their new job, enforcing the federal Prohibition law, any change in their tactics imperceptible since the law had gone into effect two months earlier. What exactly would happen to those arrested and what would be the long-term effects of this new force on his operation were serious questions for Olmstead.

Roy had been at home a few hours when the phone rang just after six a.m., his captain announcing that he knew all about the bust, as did the sheriffs office in Snohomish County, where the raid had taken place. The revenuers had recognized Lieutenant Roy Olm- stead, a well-known rising star in the Seattle Police Department, and had arrested Sergeant Tom Clark and seven others at the scene. The police car arrived at Olmsteads house minutes later, one of Olmsteads own patrolmen at the wheel, to take him down to the station. Olmstead told the officer the same thing he would later tell the police chief: he had been excused from his regular shift to care for his sick wife and daughter, knew nothing of the liquor deal, and stood ready to face his accusers.

The chief did not believe Roy, or Tom Clark, who claimed he had gone to the dock to arrest the bootleggers. Chief Warren fired them both summarily, sending Roy to the county jail to await further questioning and a statement of charges, while Clark, who had been arrested by federal agents, was jailed at the federal immigration detention station, no federal lockup being available.

The newspapers evening editions spread the news across Seattle. In recent weeks, several landings of liquor had taken place at the Meadowdale dock, alarming the station agent for the railroad, a concerned citizen who had gotten in touch with Donald A. MacDonald, State Director of the new Prohibition Unit. MacDonald had been pleased to get the tip, eager to shift focus from arrests of peddlers of a few bottles to the rumrunner of several hundred. Olmstead may have counted on the inexperience of the Prohibition Unit, but not on its luck. MacDonalds agents had almost missed the bust, three of them stumbling in the darkness, nearly shooting one another. As fast as the cars were loaded with liquor and came up the hill wed stop them, line the men up alongside the road and drive the car out of sight and gather in the next one, exclaimed the son of the railroad station agent. After they secured the cars, they went down the hill and tried to take the delivery boat. The boat captain could be heard trying to start its motors. The railroad agent fired repeatedly into its wooden hull before the engines caught and the hulking shape pulled away. Though the dark had prevented a good look at the boat, the agents thought the Coast Guard or U.S. Customs authorities would be able to identify it by all the bullet holes in its side.