Lost Recipes of Prohibition

: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, LC-DIG-npcc-00979. All botanical illustrations: Khlers Medizinal-Pflanzen. Photography of journal pages by John Schulz and Daniel Fishel (StudioSchulz). Book cover photograph by Sean Hemmerle.

Copyright 2015 by Matthew Rowley

All rights reserved

Book layout and design: Nick Caruso Design

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at or 800-233-4830

The Countryman Press

www.countrymanpress.com

A division of W. W. Norton & Company

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

www.wwnorton.com

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Rowley, Matthew B., author.

Lost recipes of Prohibition : notes from a bootlegger's manual / Matthew Rowley.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-58157-265-0 (hardcover)

1. Alcoholic beverages. 2. Drinking of alcoholic beveragesUnited StatesHistory. I. Lyon, Victor Alfred, 1876 Works. Selections. II. Title.

TP507.R69 2015

641.2'1dc23

2015028179

ISBN 978-1-58157-635-1 (e-book)

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Please bookmark your page before following any links

Here, Fritz said. He slid a little blue book toward me across a long folding table. This is more your area than mine.

Before he retired and decamped for a beach life in Thailand, Frederick C. Fritz Blank was owner and chef of the Philadelphia restaurant Deux Chemines. Now closed, the Doo, as he sometimes called it, sat on the corner of Locust and Camac in two Frank Furnessdesigned homes. For decades, it was one of the citys benchmarks of genteel dining. Some patrons addressed him as Chef Blanc. Seemed about right, Frenchifying his name like that. After all, the names of dishes on the menu were heavily Gallicpalourdes rties aux armates, quenelles de brochet la Lyonnaise, ballotine de canard, sorbet au pamplemousse, pt aux coings, and more.

But all that was in the dining room. Downstairs at the restaurant, past a long hall hung with copper pots and pans, it was another matter. In the basement kitchen, the French veneer peeled away and he was Chef Blank, not Blanc. His family was not Parisian or Lyonnais; they hailed from Pennsauken, New JerseyEast Philadelphia, he liked to jokeand, before that, from Wrttemberg in southern Germany. Staff meals downstairs were far more likely to be something from Germany, Austria, Hungary, or other parts of Mitteleuropa than from the French menu upstairs. There might be his grandmothers Kartoffelsalat (a bacon-laced potato salad), for instance, slices of the simmered bread dumpling known as Serviettenkndel, or a Czech sauerkraut soup garnished with smoked sausage and sour cream.

Our mutual obsession with books about food and drinks brought us together, although until I met Fritz around 1997 I had been self-conscious about the sheer number of books at home. As a museum curatorId earned degrees in anthropology as well as museum administrationI was acquisitive by inclination and training. What started as a handful of cookbooks to get me through cooking rudimentary meals in my first apartment during undergraduate years had metastasized into a library that spread over three floors of my home. Not just cookbooks, but all sorts of related volumes: barware catalogs, corporate histories of drinks firms, pamphlets, culinary postcards, technical manuals for making ice cream and bacon, culinary histories, and more. By the time I moved to south Philadelphia, the collection was some two thousand volumesand growing.

Blank, though, owned five times that number. In comparison, his collection made mine seem, well, pedestrian. Completely reasonable, in fact. We both claimed that these were working libraries we used every day. He had an entire wall of boxes filled with menus from restaurants around the world, and stacks upon stacks of magazines about food and beverages stretching back to the 19th century. He was a madman. Me? I was merely touched. We became good friends and, over the course of the next several years, I spent thousands of hours in his library.

Although Id handled literally tens of thousands of cookbooks, bartenders guides, manuals on livestock, butchery, and related material over my career as a collector, the format, color, and size of this little blue book was unfamiliar. Something unusual, then, something rare. I glanced at Fritz sitting nearby, but he looked away, pulling a folder from one of his research piles. I turned the book over in my hands. Gold letters glittered as light hit its spine. I frowned at the name they spelled and turned back to face him. Who is Viereck?

I have no idea. He had already pulled his glasses down from their perch on his boxy little chefs hat and was making a show of busying himself with the folders contents. Look inside.

The name bothered me. George Sylvester Viereck. An author, obviously, but something else. A friend of H. P. Lovecraft, maybe? One of his lesser-known colleagues? I did have a sizable collection of Lovecraft material at home. There was something to that, but when I cracked opened the book and began running my eyes and fingertips over the pages, any thoughts of weird fiction writers drained away. The wear on its cover, the brittle and slightly tanned paper, those vanilla smells of slow decomposition, and the archaic handwriting all suggested the thing was older than either of us at the table. The books age, however, might have been one of the few true things about it. The entire thing, from cover to cover, was a deception.

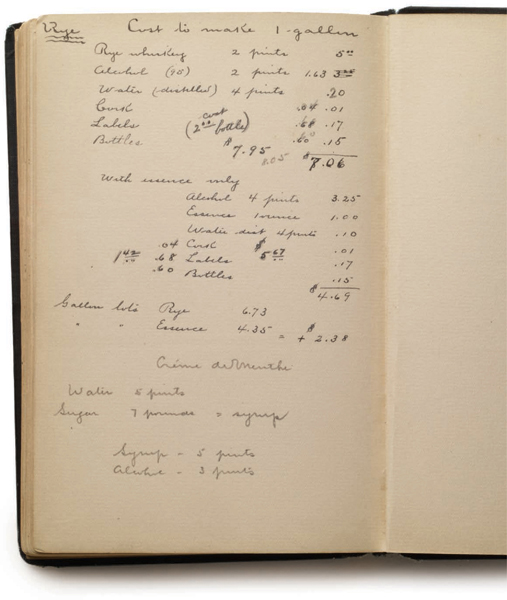

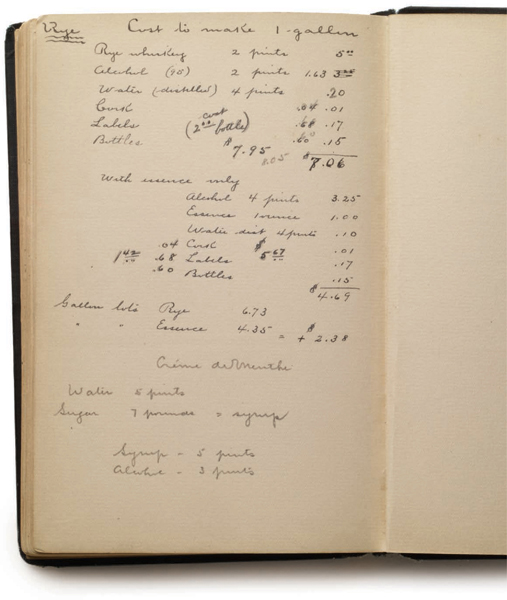

Despite the spines promise of Vierecks writing, there were no printed pages at all. Instead: hundreds of handwritten notes about, and formulas for, booze. Recipes for gin and other juniper spirits cropped up again and again; so did a dozen or so for absinthe. Cordials. Whiskeys, both real and artificial. Brandies. Not brandies for connoisseurs, but there they were along with notes on how alcohol reacts under certain conditions and how Cognac might be colored with oak extract and adjusted with syrups to get ready for market. Loose slips of paper tucked in its pages tied it to Prohibition-era New York; here was a prescription form from a Manhattan hospital, there a business card from Harlem. Flipping between the pages, I realized most of the recipes were in English, but dozens were in German, a language I hadnt spoken since I was an adolescent. There was Kmmel, Doppel Kmmel, and Eiskmmel. Latin, too, crept in as later entries veered into pharmaceutical preparations. Lotion for head lice. Salves for chilblains and cures for freckles. I looked up at Fritz. Freckles need cures?

Next page