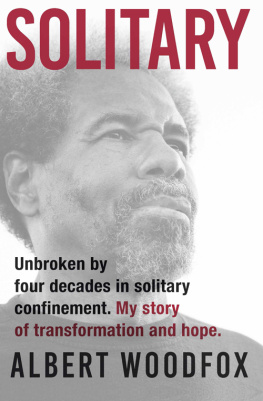

To the late C. Paul Phelps,

my mentor and friend

Success is relative.

It is what we can make of the mess we have made of things.

T. S. ELIOT

Contents

1Ruination

19421961

2Tribulation

19621970

3Solitary

January 1972

4The Jungle

19731975

5Mentor

1976

6Crackdown

1976

7Truth Behind Bars

19771981

8Disillusion

19811986

9Soldiering On

19861990

10Hope

19901994

11Censorship

19952001

12Behind Enemy Lines

20012005

13Deliverance

2005

14Heaven

2005

Authors Note

All the material in quotation marks comes from court testimony, contemporaneous notes made either by me or by others, published sources, or the best of my recollection. I have worked scrupulously to ensure that all the conversations within these pages are faithful in content, if not always to the exact words spoken.

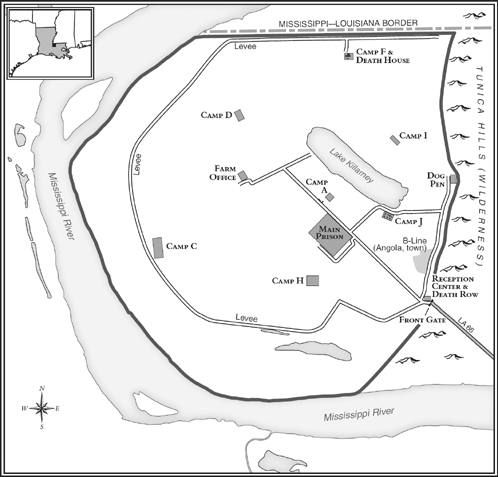

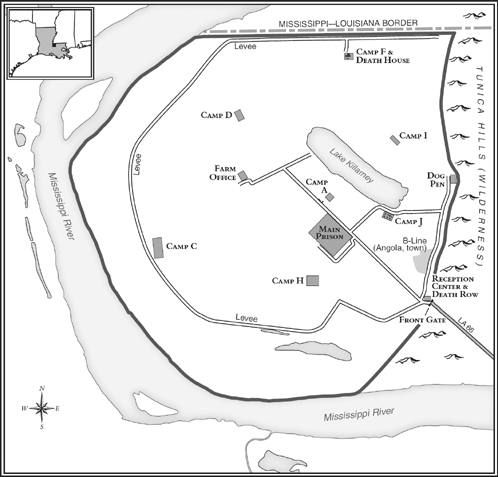

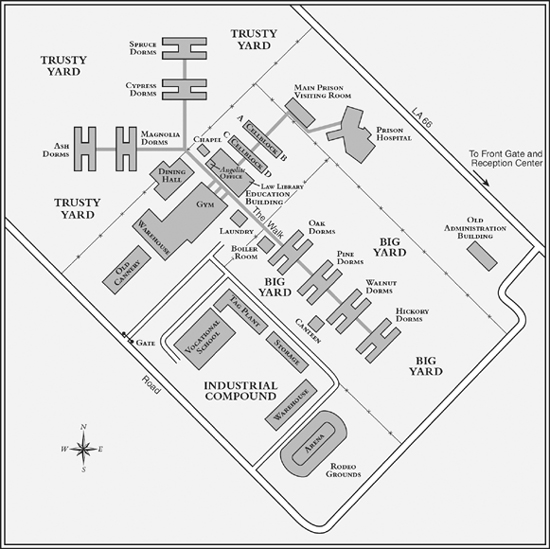

ANGOLA

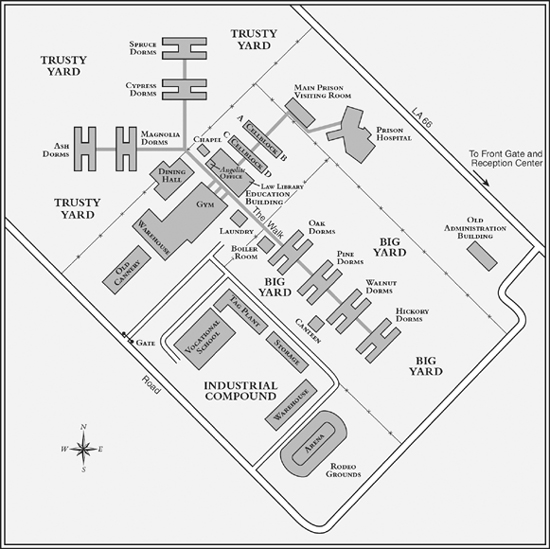

MAIN PRISON

Ruination

19421961

Kill that nigger! a voice barked into the winter night.

The headlights of the state troopers car blinded me. I was handcuffed and in my stocking feet on the shoulder of a two-lane road, standing between the headlights of their car and the taillights of the one I had been driving before they pulled me over. Murmurs ran like the scent of prey through the small crowd of shadowy figures that rustled on the roadway beyond the lights. I wondered how they had gathered so quickly. An arm punctured the pool of light as a man lunged toward me, intercepted by the young trooper who, responding to a police radio bulletin, had captured me. I didnt need to see the faces to know that they were white.

Give him to us, one man shouted.

Just give us the boy, and go on your way, another said, more kindly.

A second, older trooper looked indecisive as the crowd grew more restless. I felt only fear. The younger trooper cautiously interceded. Look, weve already called this in to headquarters. They know we have him, and theyre on the way. We cant give him up. Well never be able to explain it. The older cop fingered his holstered revolver and told the men he couldnt do what they wanted but assured them that I would be dealt with.

It was a reprieve, but I felt certain this business could end only one way. It was 1961, and we were in Louisiana.

Within minutes more official vehicles arrived, and the road was flooded with law enforcement officers huddled in talk. Then two deputy sheriffs came over, took me roughly by the arm, and hustled me to the troopers car. One of them, red-faced, punched me in my side and shoved me onto the floor of the rear seat. Then he kicked me hard with his cowboy boot as he climbed in. Uh-uhcant have that, the older trooper said. Were taking him to the sheriff.

Hes a dead sonuvabitch anyway, the deputy said, leaning back into the seat and pinning me with his foot. The policemen drove in silence. When the car slowed and turned into a gas station on the edge of the small town of Iowa, I wondered if this was where they were going to kill me. My fear virtually disconnected me from my body.

The deputy led me gruffly to a car occupied by two large white men, who got out to talk to the men who had brought me. I was led into the car, where I sat alone in the back seat, hands cuffed behind me. When the two big men returned to the car and were settled in the front seat, they turned to introduce themselves: The driver was Henry A. Ham Reid, Jr., longtime sheriff of the parish we were in, Calcasieu; the other was Deputy Charles Barrios. The sheriff had questions.

My name? Wilbert Rideau. Address? 1820 Brick Street, Lake Charles. No, its my mothers home. Age? Nineteen. I work at Halperns Fabric Shop in the Southgate Shopping Center.

Barrios got out of the car and went into the gas station.

Wheres the gun? Reid asked.

Threw it away, I said.

You have any other weapons?

A knife.

Where is it?

Threw it away.

Barrios returned. Theyre going to pick up his mother and bring her to the jail, he told the sheriff.

My mother dont have anything to do with this, I said, alarmed.

Well, youre gonna have to help us understand that, Reid said. You can start by showing us where you threw the gun and knife. I directed them off the highway and onto back roads until we reached the spot. In the dark, they couldnt find the weapons in the grassy pasture. Thirty minutes and eleven miles later we were in Lake Charles, a booming oil city of sixty-three thousand.

Its four-story brick jail rose behind the parish courthouse on Ryan Street, the major downtown traffic artery. Reid drove past the courthouse and came to an abrupt halt when he saw several hundred whites gathered in front of the jail.

We cant go through the front, Barrios said, staring at the scene before us.

Lets try the rear, Reid said, as he put the vehicle in reverse.

People recognized the sheriffs car and ran toward us. My heart raced as Reid spun the car around and drove away from the mob.

I was living the nightmare that haunted blacks in the Deep Southdeath by the mob, a dreaded heirloom handed down through the generations. We had seen the photographs, heard the tales. They would beat me and stomp me, then hang me from a tree on the courthouse lawn, castrate me, douse my body with gasoline, and set it afire. The white spectators would revel in the bonfire. Afterward they would cut off my fingers and toes, ghoulish souvenirs of white justice. Theyd leave my charred remains on display as a useful reminder.

You gonna turn me over to em? I asked the sheriff.

Thats not gonna happen, he replied. He talked into his car radio, then made his way, headlights off, creeping toward the jail, stopping beside a large stand of bushes near the jails rear parking lot. Barrios got out of the car to scout the situation.

Sheriff, youre not gonna bring my mother into that crowd? I asked.

Shell be okay, he said, staring intently down the street. Then he turned to look at me. But you have to cooperate with us. A lot of people are mad at you right now. The quicker we can get to the bottom of what happened, the quicker we can explain things and calm people downand your momma can go back home. It all depends on you.

We sat in silence until Barrios returned. We can go in through the back, he said, but we have to move fast.

The sheriff gunned the motor and sped up to an inconspicuous steel door at the back of the jail. He and Barrios leaped out of the car and sandwiched me between them, each holding me under an arm. They hurried me through the door, my feet in the air. As they spirited me into an office, I heard the roar of voices even before I saw the sea of white men stirring around in the lobby of the jail. Standing in a hallway facing them were more white men, in uniforms, with gunsplenty of guns.

The office door closed, leaving me alone with a handful of men. Barrios removed my handcuffs and seated me in a chair next to a wooden desk. He offered me water and a cigarette, which I accepted. The sheriff soon returned, pulled up a chair to face me, and asked if I was okay. I nodded.

I need you to tell me what happened, he said in a kindly voice. Start from the beginning.