Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

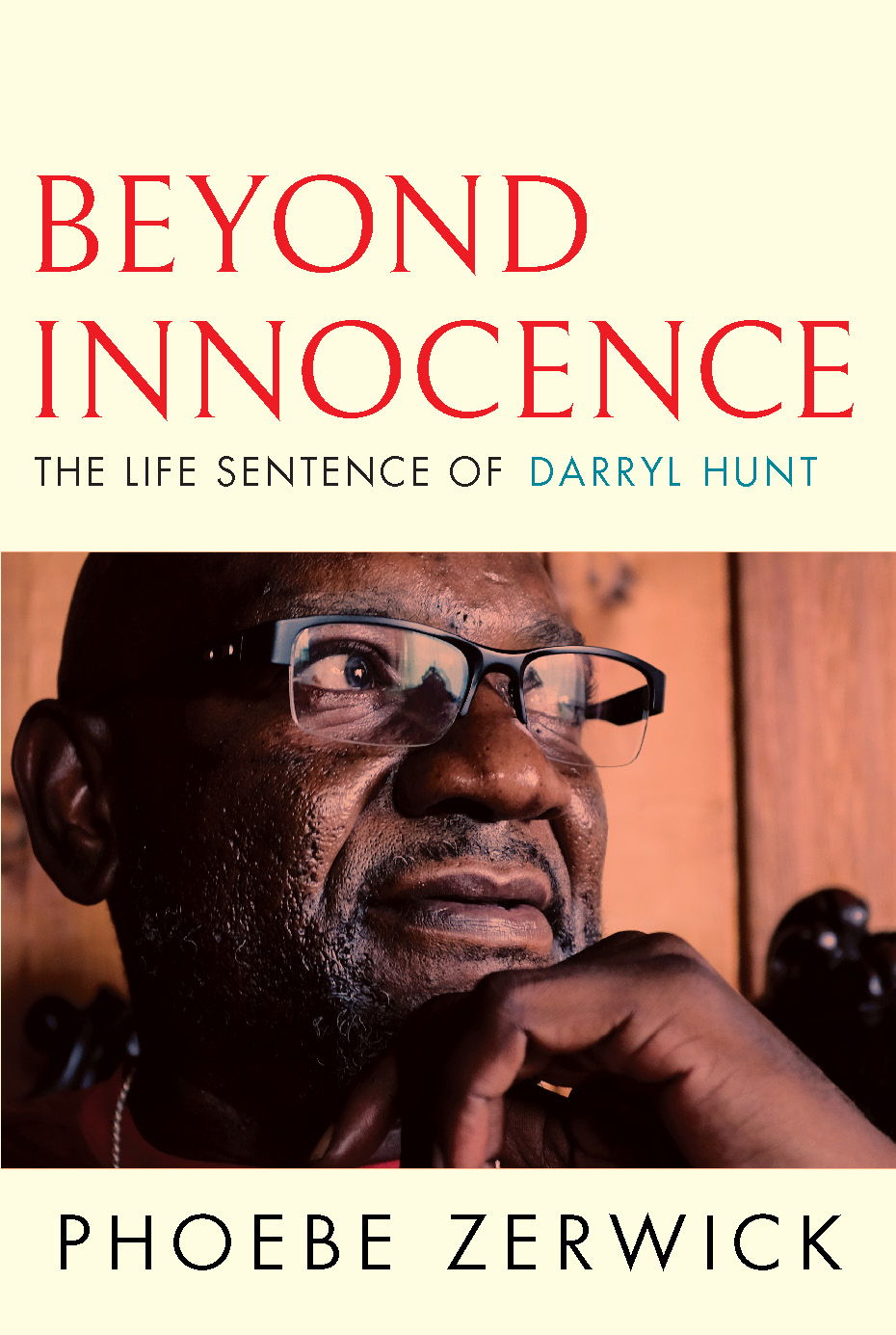

BEYOND INNOCENCE

THE LIFE SENTENCE OF DARRYL HUNT

A true story of race, wrongful conviction, and an American reckoning still to come

PHOEBE ZERWICK

Atlantic Monthly Press

New York

Copyright 2022 by Phoebe Zerwick

Jacket design by Becca Fox Design

Jacket photograph of Darryl Hunt by Andrew Dye,

2014 Winston-Salem Journal

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or .

FIRST EDITION

Epigraph from Essay on Reentry: for Fats, Juvie & Star from Felon: Poems 2019 by Reginald Dwayne Betts. Reproduced by permission of W. W. Norton.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Printed in Canada

First Grove Atlantic edition: March 2022

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is available for this title.

ISBN 978-0-8021-5937-3

eISBN 978-0-8021-5939-7

Atlantic Monthly Press

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

Contents

Dedicated to Darryl E. Hunt

No words exist for the years we lost

to prison.

Reginald Dwayne Betts, from Essay on Reentry:for Fats, Juvie & Star

Authors Note

Beyond Innocence is my attempt to finish a story I began long ago, in 2003, when I wrote about the wrongful conviction of Darryl Hunt for the Winston-Salem Journal. Hunt was in prison then for the 1984 murder of a newspaper editor who had been raped and stabbed to death, not far from the newsroom where I worked. But a claim of innocence is no defense, and only after 19 years of legal battles and the tireless effort of local activists was Hunt released. It was a triumphant moment for him, for his supporters, and for me.

Its not that case of innocence, however, that led me to this book, but rather what happened over the next 12 years, after Hunt was exonerated by DNA evidence, after he became a champion for justice, after the trauma he had endured finally caught up with him.

To the outside world, Hunt was the man who walked out of prison without rancor or regret. But the past haunted him, and the heroic narrative of a man who fought for justice masked a deep despair.

I first heard about his case when I arrived in North Carolina in July 1987, fresh out of journalism school, having headed south from New York City to a region that felt rich in stories. Most of the other reporters at the Journal were my age, in their mid- to late twenties, all of us looking to launch a career in a state known as a training ground for journalism. Two of my new coworkers proposed a tour one Saturday of local landmarks, ending with lunch of barbecue, pinto beans, and sweet tea.

The first stop was an overgrown park, two blocks away from the back door to the newsroom. I dont remember if we walked or drove, or if I noticed the odd fence made of wood pilings, or the trash that littered the hillside. They told me about Deborah Sykes, a copy editor at the former afternoon newspaper who, three years earlier, had been raped and stabbed to death there one summer morning. She was 25 when she died, young and ambitious like me. They told me, too, that a Black teenager named Darryl Hunt had been convicted in her death and that the case had become a flashpoint in the citys racial politics. Many Black people in town believed that he had been railroaded. It was a story I would need to understand if I was going to understand this place I now called home.

In the 1980s, Winston-Salem was an industrial city of the New South. The R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, headquartered in an art deco building that was the model for the Empire State Building, anchored one downtown corner, and Wachovia Bank, long considered one of the strongest banks in the nation, stood across the street. Piedmont Airlines, HanesBrands, and McLean Trucking were headquartered in town, too. Of these Fortune 500 companies, Reynolds defined the city, filling the air with the sweet smell of tobacco. The Camels my brother smoked were made here. So were Winstons, Salems, and Dorals. In the fall, farmers came to town to sell piles of flue-cured leaves at auction. And in the newsroom, in deference to our readers and to the citys largest employer, we didnt state as fact that cigarettes caused cancer but hedged with the attribution of some medical experts say.

It was also a city divided by the murder of a white newspaper editor and the conviction of a Black teenager. I grew up in New York City and went to college on the South Side of Chicago, so I knew how crime can define a community, and I knew enough about American history to know, even to expect, that race would be the subtext of much of what I would write about.

I began working as a bureau reporter in Lexington, a furniture town a half hour south of Winston-Salem, with enough character to satisfy my romantic notions of the South. The sheriff, Paul R. Jaybird McCrary, ran the local Democratic Party machine. His detectives made fun of the New Yorker the paper had sent to town, but they were kind to me and let me read through their case files and follow them around crime scenes. And I learned about Southern justice from the district attorney, H. W. Butch Zimmerman, whose office was decorated with Confederate memorabilia. Defense attorneys would gather there on Friday afternoons while he read excerpts from his collection of slaveholder diaries, many about their sexual exploits with enslaved women, recited not as stories of rape but for the entertainment of the men in the room. Zimmerman tried the murder cases himself, and lawyers from as far away as Raleigh and Charlotte would come to watch him and to learn from his legendary courtroom theatrics. He rarely lost.

The subtext of racism was not as obvious in Winston-Salem as it was in small-town North Carolina, but it was far from hidden. The city council, then known as the board of aldermen, was divided by race, with four Black and four white members. Often the members agreed, but when they did not, the division typically fell along racial lines. Black aldermen supported naming the local coliseum after a Black Vietnam War hero; white aldermen did not. Black aldermen voted to establish a police review board. White aldermen opposed it. The mayor, a white woman and a Democrat, broke those ties, and when she sided with the Black Democrats on the board, business leaders saw her as weak.

Other reporters wrote about Hunts case over those years in the neutral style we all accepted as objective journalism. The stories dutifully quoted his supportersmen like Larry Little, who in the 1970s had founded the local Black Panther Party, and Rev. Carlton Eversley, who had moved south from New York City in the hopes of becoming an activistwho claimed that Hunt was the innocent victim of a racist justice system. And the stories just as dutifully quoted police and prosecutors who insisted that the evidence against Hunt was rock solid. From that balanced perspective, it seemed impossible that after two trials, three layers of appellate review, and the tireless efforts of attorneys, that a truly innocent man could be imprisoned.