FIRE IN THE CITY

ALSO BY LAURO MARTINES

Non-Fiction

The Social World of the Florentine Humanists

Lawyers and Statecraft in Renaissance Florence

Violence and Civil Disorder in Italian Cities, 12001500

(editor)

Not in Gods Image: Women in History from the Greeks to the Victorians

(with Julia OFaolain)

Power and Imagination: City-States in Renaissance Italy

Society and History in English Renaissance Verse

An Italian Renaissance Sextet: Six Tales in Historical Context

Strong Words: Writing and Social Strain in the Italian Renaissance

April Blood: Florence and the Plot Against Medici

Fiction

Loredana: A Venetian Tale

FIRE IN THE CITY

SAVONAROLA AND THE STRUGGLE

FOR RENAISSANCE FLORENCE

LAURO MARTINES

Oxford University Press, Inc., publishes works that

further Oxford Universitys objective of excellence

in research, scholarship, and education.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Copyright 2006 by Lauro Martines

Published by Oxford University Press, Inc.

198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York 10016

www.oup.com

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without the prior permission of Oxford University Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Martines, Lauro.

Fire in the city: Savonarola and the struggle for the soul of

Renaissance Florence / by Lauro Martines.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-19-517748-0 (alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-19-517748-7 (alk. paper)

1. Savonarola, Girolamo, 14521498.

2. Florence (Italy)History14211737.

3. Florence (Italy)Politics and government14211737.

4. Florence (Italy)Church history.

5. ReformersItalyFlorenceBiography.

6. DominicansItalyFlorenceBiography.

7. Florence (Italy)Biography.

I. Title.

DG737.97.M3 2006

9455105092dc22 2005031802

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed in the United States of America

on acid-free paper

al mio carissimo jairo, un gigante a modo suo

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

M Y IRREDEEMABLE DEBT must be to the Savonarola experts living and dead, whose labours and intelligence made this book possible. Without their work, not a single page of what I have done here would exist. They are all cited in the notes, comments, and Bibliography. The writing of history in the modern world, at all eventscan never be anything but a team enterprise. Those of us who forget this belong to the demon of ingratitude.

Yet once more I have the happy obligation to thank my publishers, Will Sulkin and Peter Ginna, superb readers and editors. In my years as an academic, never did I have critics and commentators as alert and perceptive as they. The university world is far from having all the best of what there is in imaginative talent and intellectual rigour.

My friend and agent, Kay McCauley, an ongoing inspiration, knows how much she is appreciated, but an expression of public thanks can never be wrong. My first reader, as always, Julia OFaolain, deserves all that the heart can offer,

All translations are mine, unless otherwise indicated.

Lauro Martines

London

Autumn, 2005

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

1. Nerli Altarpiece, detail of the San Frediano gate in Florence, 1494 by Filippino Lippi. Santo Spirito, Florence. (Bridgeman)

2. Porta San Frediano, Florence. ( 1990, Photo Scala, Florence)

3. Profile of King Charles VIII, King of France, by the Florentine School. Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence. (Alinari Archives Florence)

4. Portrait of Pope Alexander VI, Spanish School. Vatican, Pinacoteca ( 1990, Photo Scala, Florence)

5. Piazza Signoria, Florence, 1890. (Alinari Archives Florence)

6. Interior of the Florence Cathedral. (Alinari Archives Florence)

7. Detail St Francis receiving the Rule of the Order from Pope Honorius, scene from the cycle of the Life of St Francis of Assisi, 1486 (fresco) by Domenico Ghirlandaio (Domenico Bigordi). Sassetti Chapel, Santa Trinita, Florence. (Bridgeman)

8. The Medici Palace, Florence. (Alinari Archives Florence)

9. The Strozzi Palace, Florence, 1924. (Alinari Archives Florence)

10. Bust of Niccol Machiavelli in profile, polychrome terracotta, in the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence. (Alinari Archives Florence)

11. The Bargello, c. 12561350 (photo) by Italian School. Via del Proconsolo, Florence. (Bridgeman)

12. The Execution of Savonarola (145298), by Italian School, (oil on panel, 15th century). Museo di San Marco, Florence. (Bridgeman)

13. The Lady with the Ermine (Cecilia Gallerani), 1496 by Leonardo da Vinci (oil on walnut panel) Czartoryski Museum, Cracow, Poland. (Bridgeman)

14. Bust of Cardinal Giovanni de Medici, ascribed to Antonio de Benintendi. (Courtesy of the Trustees of the Victoria & Albert Museum)

An X-Ray of

Florentine Government

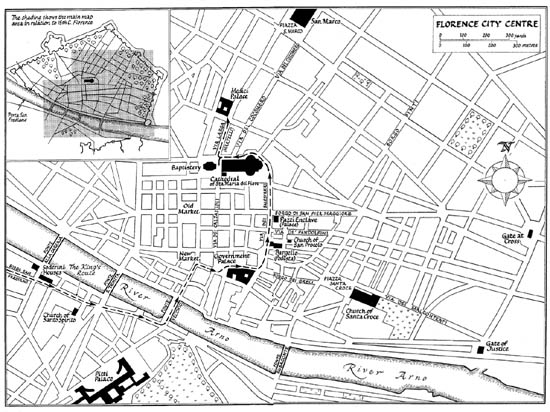

G overnment in Florence was the job of a pyramid of small councils, with the Signoria or Signory eight Priors and the Gonfalonier of Justice at the apex. These nine men held office for two months, and were then replaced by a new group. The city thus saw six changes of government per year. Although seemingly unstable, the system worked very effectively for more than two centuries, because other councils were drawn in to support the Signory.

Two bodies of counsellors, the Twelve Good Men and the Sixteen Gonfaloniers, worked closely with the Signory. They spoke for the different parts of the city and voted on most matters of importance. Their short office terms were staggered, so that the incoming (new) Signory always meshed, so to speak, with counsellors who were fully on top of the current political situation.

In wartime and periods of danger, the Signoria shared diplomatic power with the War-Office Ten, who served for six months or a year and who conducted the war. If the Ten were renewed, owing to strains in foreign affairs, they could be re-elected.

The Eight, a political and criminal police, were continually consulted by the Signory. Like the Sixteen, the Twelve, and the Ten, they met in the government palace, the Palazzo della Signoria.

Everyday Florence, then, was ruled by a cluster of offices. The Signoria took the initiative and introduced all new bills to the Great Council, but only after sustained consultation. Offices were filled by lot or, in part, by election in the Great Council. Action

Next page