O THER BOOKS BY L AURO M ARTINES:

The Social World of the Florentine Humanists (1963)

Lawyers and Statecraft in Renaissance Florence (1968)

Violence and Civil Disorder in Italian Cities, 12001500 (1972)

Not in Gods Image: Women in History from the Greeks to the Victorians (1973), with Julia OFaolain

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK,

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF, INC.

Copyright 1979 by Lauro Martines

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York.

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Martines, Lauro. (Date)

Power and imagination, city-states in Renaissance Italy.

Bibliography: p.

1. ItalyPolitics and government476-1268.

2. ItalyPolitics and government12681559.

3. Cities and townsItalyHistory. 4. Italy

Civilization476-1268. 5. ItalyCivilization1268

1559. I. Title.

DG494.M37 1979 945 78-11666

eISBN: 978-0-307-83093-7

v3.1

CONTENTS

Illustrations follow

PREFACE

T he story to be told here begins in the eleventh century, with the rise of warlike cities and their rush, under the leadership of communes, to seize local political power. The years around 1300 betray a break in development: urban Italy passes from one stage to another. The first stage is, however, an organic part of the period as a whole, for the Italian Renaissance issued forth in two grand stages. The first, lasting to about 1300, saw the laying of a basic groundwork: the physical building of cities and the rise of a new economy, a new society, new states, and a new set of vivid, shaping values. In the second stage, extending from about 1300 to the late sixteenth century, high cultureliterature, art, and ideaspushed forward and became more prominent, more important. But the achievement of the second stage was vitally rooted in the resources and values of the first. No other validation is needed, it seems to me, for giving the eleventh and twelfth centuries a place in this history.

The title Power and Imagination is my way of referring to, and altering, the more conventional distinction between society and culture. In telling a story which courses across five centuries, I was driven to pursue a central theme, a thread more easily visible than society. I chose to center attention on the fortunes of power because, in tracing the movement of political authority, I was also compelled, all the way along, to track the direction of social and economic change. And I chose imagination over culture because my supreme concern is with relations between dominant social groups (power) and the articulated, formal, refined, or idealizing consciousness of those who speak for the powerful. In this interplay, the workings of imagination tend to be foremost.

Lauro Martines

Florence, Los Angeles, London

19661978

CHAPTER 1

THE ASCENT OF COMMUNES

BACKGROUND

I t is hard to summarize chaos, yet the narrative history of Italy in the eleventh and early twelfth centuries is a story of political wreckage and confused authority. An image for the age is from the spring of 1121, when the antipope Gregory VIII was led into Rome sitting backward on a camela gesture of disgrace and howling derision; fitting too, in view of the preeminence of violence. For eleventh-century kings and popes were deposed, physically assaulted, or driven into flight as if no better than small game. Bishops and feudal lords were scattered like leaves; some were murdered, maimed, or merely brushed aside, while others, such as Alrico, bishop of Asti, were cut down in full battle gear (1035). Authority had been laid low.

Power in upper Italy was received or seized from the hands of weak kings in the tenth century, with the result that government passed increasingly to the control of feudal magnates. In the eleventh century the fragmentation of authority went further: real power ended by being local power in the hands of local magnates, usually bishops, though it was soon enough claimed or grabbed by cities.

With the end of the Carolingian kings and of others drawn mostly from among the peninsulas Frankish and Lombard feudatories, Italy north of Rome turned to a line of German kings, beginning with the Ottonians (962), who managed dangerously to wear three crownsthe crown of Germany, the iron crown of the Italic kingdom (upper Italy), and the crown of the Holy Roman Empire. They would wage a bitter and vain struggle, centuries long, to impose some kind of central rule on their Italian territories. Their invincible opponents were Roman popes, feudal and episcopal potentates, and a teeming expanse of self-willed cities.

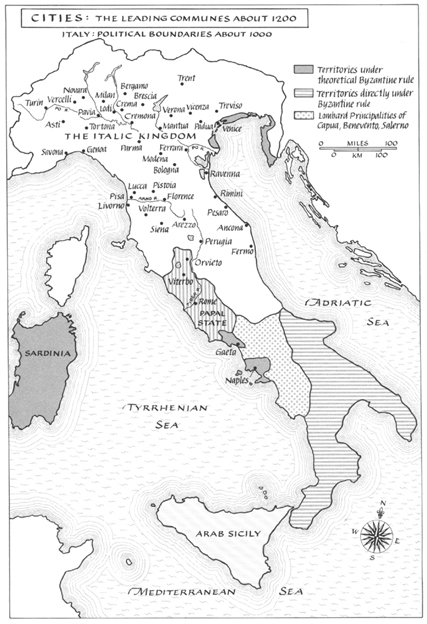

Italy was nothing more than a geographic expressionthe Italian peninsula. Nearly all the upper part belonged to the German kings. In 961, traveling south across the Alps, the king-elect, Otto I, made for the royal capital of Pavia, where he donned the iron crown of Lombardy and then went on to Rome to be crowned Holy Roman Emperor. The Italic kingdom (Map 1) stretched from the southern Alps, taking in the whole northern plain but excluding Venice, down to central Italy along both coasts. Papal territory was the entire region around Rome, from Perugia to Terracino, but reaching only halfway across the narrow width of the peninsula. Next south, on the western side, were the independent principalities of Benevento and Salerno; and farther south still, travelers entered Byzantine territory, which included Naples and the entire foot of the peninsula. Sicily was under Arab rule until the Norman conquest in the 1070s.

The geographic focus of this history will be the Italic kingdom, where dozens of cities were to make an armed bid for independence and the strongest converted themselves into petty empires and city-states.

Apart from their wars in Germany, the emperors of the eleventh century were plagued by four problems in Italy: (1) the rebelliousness of cities and mighty vassals, (2) a blazing reform movement directed against a simonist clergy, (3) the resolute violence of papal factions and a riotous baronage in Rome, and (4) the menacing pressure in southern Italy of Byzantine and especially Norman armies. Each of the centurys triple sovereigns was harried by two or more of these. Henry II (10021024) spent his expeditions to Italy mainly in a struggle against the supporters of his rival for the Lombard crown, the Marquis Arduin, a Piedmontese magnate. The news of Henrys death was greeted with an uprising in Pavia, capital of the kingdom, and the populace set fire to the government palace. Feeling against the royal establishment was rife. Conrad II (10241039) took the field against Pavia and had also to wage wars against stubborn feudatories, Roman noblemen, Milan, and the proud and powerful archbishop of Milan, Ariberto, whom he deposed. He also seized the bishops of Cremona, Vercelli, and Piacenza and packed them off to prison in Germany, thereby making formidable enemies in those cities. Henry III (10391056) enjoyed more peaceful relations with the Church. He inherited, however, the struggle against Ariberto and the big Milanese nobility, and he had formidable opponents in his own vassals, the lords of Canossa, in the antipopes Silvester III and Benedict IX, in their prepotent Roman backers, and then, in 10521053, in the reformer Pope Leo IX. The reign of Henry IV (10561106), which included the years of a regency, was a tumult of criticism against the immoral life and economic practices of the cathedral clergy. Concubinage, simony, and the lay investiture of bishops came under violent attack. The consecrated bread of simonists was called manure and their churches were called stables. The wars of investiture peaked, and every one of Henry IVs trips to Italy must have aged him as he found himself in mortal combat with a reformist papacy, with rebellious cities, and with the prestigious house of Canossa, while also scurrying around to hold on to the allegiance of other cities and of his imperial bishops. Henry fought, in effect, to maintain imperial control over the feudal Church, whose economic and social relations with the entire class of vassals formed a tough membrane which could not be broken save by damage to the landed wealth of the great feudal nobility.