THE ENCIRCLED RIVER

My bandanna is rolled on the diagonal and retains water fairly well. I keep it knotted around my head, and now and again dip it into the river. The water is forty-six degrees. Against the temples, it is refrigerant and relieving. This has done away with the headaches that the sun caused in days before. The Arctic sunpenetrating, intenseseems not so much to shine as to strike. Even the trickles of water that run down my T-shirt feel good. Meanwhile, the riverthe clearest, purest water I have ever seen flowing over rocksbreaks the light into flashes and sends them upward into the eyes. The headaches have reminded me of the kind that are sometimes caused by altitude, but, for all the fact that we have come down through mountains, we have not been higher than a few hundred feet above the level of the sea. Drifting nowa canoe, two kayaksand thanking God it is not my turn in either of the kayaks, I lift my fish rod from the tines of a caribou rack (lashed there in mid-canoe to the duffel) and send a line flying toward a wall of bedrock by the edge of the stream. A grayling comes up and, after some hesitation, takes the lure and runs with it for a time. I disengage the lure and let the grayling go, being mindful not to wipe my hands on my shirt. Several daysin use, the shirt is approaching filthy, but here among grizzly bears I would prefer to stink of humanity than of fish.

Paddling again, we move down long pools separated by short white pitches, looking to see whatever might appear in the low hills, in the cottonwood, in the white and black spruceand in the river, too. Its bed is as distinct as if the water were not there. Everywhere, in fleets, are the oval shapes of salmon. They have moved the gravel and made redds, spawning craters, feet in diameter. They ignore the boats, but at times, and without apparent reason, they turn and shoot downriver, as if they have felt panic and have lost their resolve to get on with their loving and their dying. Some, already dead, lie whitening, grotesque, on the bottom, their bodies disassembling in the current. In a short time, not much will be left but the hooking jaws. Through the surface, meanwhile, the living salmon broach, freshenmake long, dolphinesque flights through the airthen fall to slap the water, to resume formation in the river, noses north, into the current. Looking over the side of the canoe is like staring down into a sky full of zeppelins.

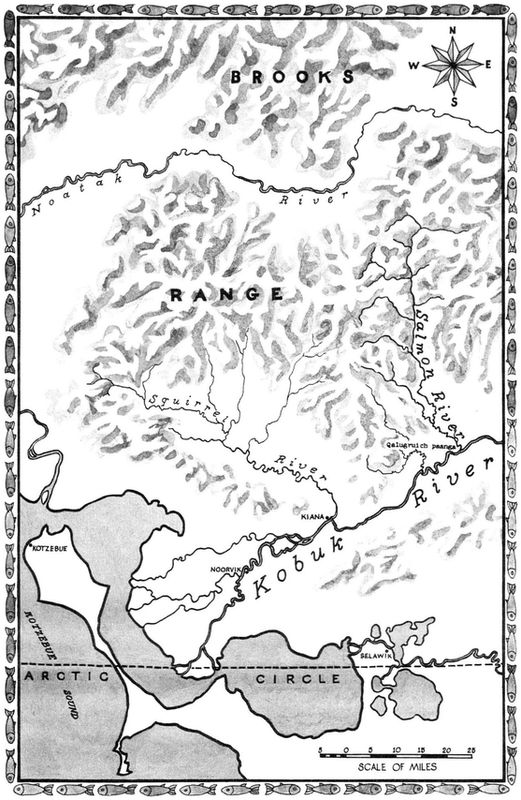

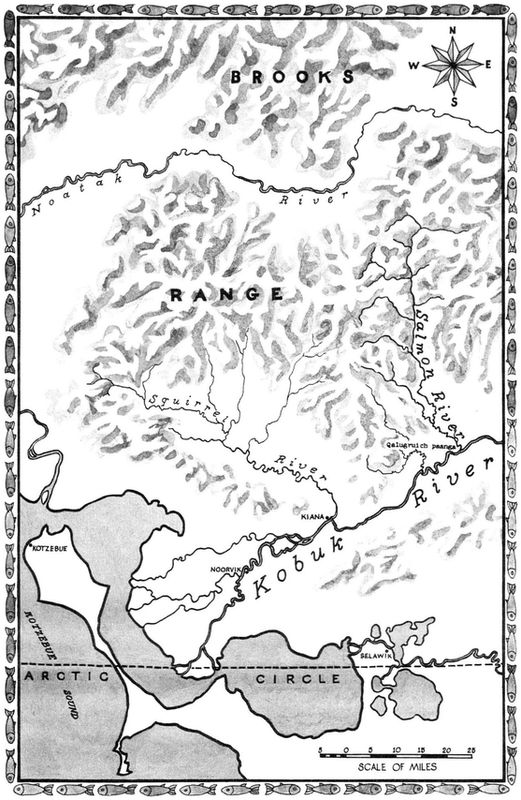

A cloud, all black and silver, crosses the sun. I put on a wool shirt. In Alaska, where waters flow in many places without the questionable benefit of names, there are nineteen streams called Salmonthirteen Salmon Creeks, six Salmon Riversof which this one, the Salmon River of the Brooks Range, is the most northern, its watershed wholly above the Arctic Circle. Rising in treeless alpine tundra, it falls south into the fringes of the boreal forest, the taiga, the upper limit of the Great North Woods. Tree lines tend to be digital here, fingering into protected valleys. Plants and animals are living on margin, in cycles that are always vulnerable to change. It is five oclock in the afternoon. The cloud, moving on, reveals the sun again, and I take off the wool shirt. The sun has been up fourteen hours, and has hours to go before it sets. It seems to be rolling slowly down a slightly inclined plane. A tributary, the Kitlik, comes in from the northwest. It has formed with theSalmon River a raised, flat sand-and-gravel mesopotamiaa good enough campsite, and, as a glance can tell, a fishing site to exaggerate the requirements of dinner.

There are five of us, four of whom are a state-federal study team. The subject of the study is the river. We pitch the tents side by side, two Alpine Draw-Tite tents, and gather and saw firewood: balsam poplar (more often called cottonwood); sticks of willow and alder; a whole young spruce, tip to root, dry now, torn free upriver by the ice of the breakup in spring. Tracks are numerous, coming, going, multidirectional, tracks wherever there is sand, and in gravel if it is fine enough to have taken an impression. Wolf tracks. The pointed pods of moose tracks. Tracks of the barren-ground grizzly. Some of the moose tracks are punctuated with dewclaws. The grizzlies big toes are on the outside.

The Kitlik, narrow, and clear as the Salmon, rushes in white to the larger river, and at the confluence is a pool that could be measured in fathoms. Two, anyway. With that depth, the water is apple green, and no less transparent. Salmon and grayling, distinct and dark, move into, out of, around the pool. Many grayling rest at the bottom. There is a pair of intimate salmon, the male circling her, circling, an endless attention of rings. Leaning over, watching, we nearly fall in. The gravel is loose at the rivers edge. In it is a large and recently gouged excavation, a fresh pit, close by the water. It was apparently made in a thrashing hurry. I imagine that a bear was watching the fish and got stirred up by the thought of grabbing one, but the water was too deep. Excited, lunging, the bear fell into the pool, and it flailed back at the soft gravel, gouging the pit while trying to get enough of a purchase to haul itself out. Who can say? Whatever the story may be, the pit is the sign that is trying to tell it.

It is our turn now to fish in the deep pool. We are having grayling for dinnerArctic grayling of firm delicious flesh. On their skins are black flecks against a field of silvery iridescence.Their dorsal fins fan up to such height that grayling are scalemodel sailfish. In the cycles of the years, and the millennia, not many people have fished this river. Forest Eskimos have long seined at its mouth, but only to the third bend upstream. Eskimo hunters and woodcutters, traversing the Salmon valley, feed themselves, in part, with grayling. In all, perhaps a dozen outsiders, so far as is known, have travelled, as we have, in boats down the length of the river. Hence the grayling here have hardly been, in the vernacular of angling, fished out. Over the centuries, they have scarcely been fished. The fire is high now and is rapidly making coals. Nineteen inches is about as long as a grayling will grow in north Alaska, so we agree to return to the river anything much smaller than that. As we do routinely, we take a count of the number neededsee who will share and who can manage on his own the two or three pounds of an entire fish. Dinner from our supplies will come in hot plastic water bags and be some form of desiccated mail-order stewMountain House Freeze Dried Caribou Cudfollowed by Mountain House Freeze Dried fruit. Everyone wants a whole fish.

Five, then. Three of us pick up rods and address the river Bob Fedeler, Stell Newman, and I. Pat Pourchot, of the federal Bureau of Outdoor Recreation, has not yet cast a line during the trip. As he puts it, he is phasing himself out of fishing. In his work, he makes many river trips. There will always be people along who want to fish, he reasons, and by removing himself he reduces the number. He has wearied of take-and-put fishing, of molesting the fish, of shocking the ones that, for one reason or another, go back. He says he wonders what kind of day a fish will have after spending some time on a hook. John Kauffmann has largely ignored the fishing, too. A National Park Service planner who has been working for five years in Arctic Alaska, he is a New England mastertouch dry-fly fisherman, and up here his bamboo ballet is regarded as effete. Others taunt him. He will not rise. But neither will the graylingto his Black Gnats, his Dark Cahills, his Quill Gordons. Sotall, angularhe sits and observes, and his short gray beard conceals his disgust. He does agree to time the event. He looks at his watch. Invisible lines, glittering lures go spinning to the river, sink in the pool. The rods bend. Grayling do not sulk, like the salmon. They hit and go. In nine minutes, we have our five. They are seventeen, eighteen inches long. We clean them in the Kitlik, with care that all the waste is taken by the stream. We have a grill with us, and our method with grayling is simply to set them, unscaled, fins intact, over the fire and broil them like steaks. In minutes, they are ready, and beneath their skins is a brown-streaked white flesh that is in no way inferior to the meat of trout. The sail, the dorsal fin, is an age-old remedy for toothache. Chew the fin and the pain subsides. No one has a toothache. The fins go into the fire.

My bandanna is rolled on the diagonal and retains water fairly well. I keep it knotted around my head, and now and again dip it into the river. The water is forty-six degrees. Against the temples, it is refrigerant and relieving. This has done away with the headaches that the sun caused in days before. The Arctic sunpenetrating, intenseseems not so much to shine as to strike. Even the trickles of water that run down my T-shirt feel good. Meanwhile, the riverthe clearest, purest water I have ever seen flowing over rocksbreaks the light into flashes and sends them upward into the eyes. The headaches have reminded me of the kind that are sometimes caused by altitude, but, for all the fact that we have come down through mountains, we have not been higher than a few hundred feet above the level of the sea. Drifting nowa canoe, two kayaksand thanking God it is not my turn in either of the kayaks, I lift my fish rod from the tines of a caribou rack (lashed there in mid-canoe to the duffel) and send a line flying toward a wall of bedrock by the edge of the stream. A grayling comes up and, after some hesitation, takes the lure and runs with it for a time. I disengage the lure and let the grayling go, being mindful not to wipe my hands on my shirt. Several daysin use, the shirt is approaching filthy, but here among grizzly bears I would prefer to stink of humanity than of fish.

My bandanna is rolled on the diagonal and retains water fairly well. I keep it knotted around my head, and now and again dip it into the river. The water is forty-six degrees. Against the temples, it is refrigerant and relieving. This has done away with the headaches that the sun caused in days before. The Arctic sunpenetrating, intenseseems not so much to shine as to strike. Even the trickles of water that run down my T-shirt feel good. Meanwhile, the riverthe clearest, purest water I have ever seen flowing over rocksbreaks the light into flashes and sends them upward into the eyes. The headaches have reminded me of the kind that are sometimes caused by altitude, but, for all the fact that we have come down through mountains, we have not been higher than a few hundred feet above the level of the sea. Drifting nowa canoe, two kayaksand thanking God it is not my turn in either of the kayaks, I lift my fish rod from the tines of a caribou rack (lashed there in mid-canoe to the duffel) and send a line flying toward a wall of bedrock by the edge of the stream. A grayling comes up and, after some hesitation, takes the lure and runs with it for a time. I disengage the lure and let the grayling go, being mindful not to wipe my hands on my shirt. Several daysin use, the shirt is approaching filthy, but here among grizzly bears I would prefer to stink of humanity than of fish.