Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Gordon Gund,

who doesnt miss a word, and

For Yolanda Whitman,

who is unreluctant to say when words

are missing, and

To half a thousand Princeton students,

who have heard it all before.

This book derives from eight essays on the writing process that have appeared in The New Yorker . One of themCheckpointswas included in a miscellaneous collection called Silk Parachute , but to a far greater extent belongs here, and is republished here.

In the late nineteen-sixties, I was working in rented space on Nassau Street up a flight of stairs and over Nathan Kasrel, Optometrist. Across the street was the main library of Princeton University. Across the hall was the Swedish Massage. Operated by an Austrian couple who were nearing retirement and had been there for decades, it was a legitimate business. They massaged everything from college football players to arthritic ancients, and they didnt give sex. This, however, was the era when massage became a sexual synonym, and most eveningsavoiding writing, looking down from my window on the passing sceneI would see men in business suits stop, hesitate, look around, and then move toward the glass door at the foot of the stairs. Eventually, the Austrians had to scrape the words Swedish Massage off the door, and replace them with a hanging sign they removed when they went home at night. Meanwhile, the men kept arriving at the top of the stairs, where neither door was marked. When they knocked on mine and I opened it, their faces fell dramatically as the busty Swede they expected turned into a short and bearded man.

In this context, I wrote three related pieces that became a book called Encounters with the Archdruid . To a bulletin board I had long since pinned a sheet of paper on which I had written, in large block letters, ABC/D. The letters represented the structure of a piece of writing, and when I put them on the wall I had no idea what the theme would be or who might be A or B or C, let alone the denominator D. They would be real people, certainly, and they would meet in real places, but everything else was initially abstract.

That is no way to start a writing project, let me tell you. You begin with a subject, gather material, and work your way to structure from there. You pile up volumes of notes and then figure out what you are going to do with them, not the other way around. In 1846, in Grahams Magazine , Edgar Allan Poe published an essay called The Philosophy of Composition, in which he described the stages of thought through which he had conceived of and eventually written his poem The Raven. The idea began in the abstract. He wanted to write something tonally sombre, sad, mournful, and saturated with melancholia, he knew not what. He thought it should be repetitive and have a one-word refrain. He asked himself which vowel would best serve the purpose. He chose the long o. And what combining consonant, producibly doleful and lugubrious? He settled on r. Vowel, consonant, o, r. Lore. Core. Door. Lenore. Quoth the Raven, Nevermore. Actually, he said nevermore was the first such word that crossed his mind. How much cool truth there is in that essay is in the eye of the reader.

Nonetheless, I was doing something like it when I put ABC/D on the wall. For more than a decade, first at Time magazine and then at The New Yorker , I had been writing profileseach, by definition, portraying an individual. At Time , I did countless sketches, long and short, of show-business people (Richard Burton, Sophia Loren, Barbra Streisand, et al.), and at The New Yorker even longer pieces, on an athlete, a headmaster, an art historian, an expert on wild food. After ten years of that, I was a little desperate to escalate, or at least get out of a groove that might turn into a rut.

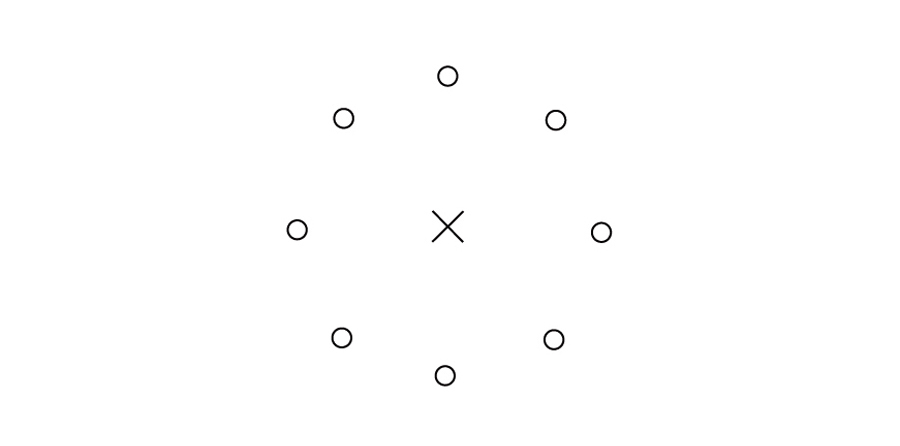

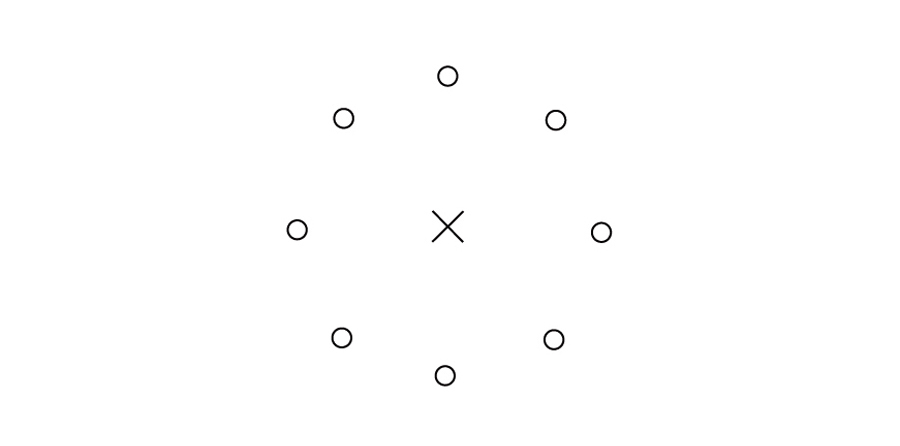

To prepare a profile of an individual, the reporting endeavor looks something like this:

The X is the person you are principally going to talk to, spend time with, observe, and write about. The Os represent peripheral interviews with people who can shed light on the life and career of Xher friends, or his mother, old teachers, teammates, colleagues, employees, enemies, anybody at all, the more the better. Cumulatively, the Os provide triangulationa way of checking facts one against another, and of eliminating apocrypha. Writers like Mark Singer and Brock Brower have said that you know youve done enough peripheral interviewing when you meet yourself coming the other way.

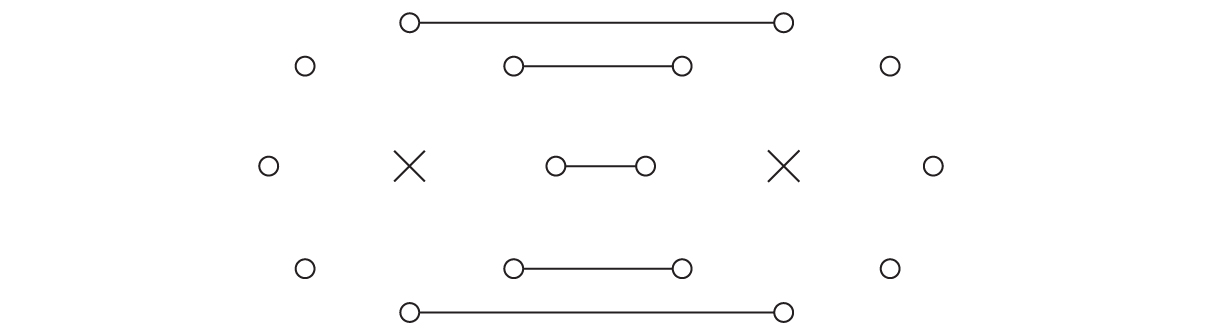

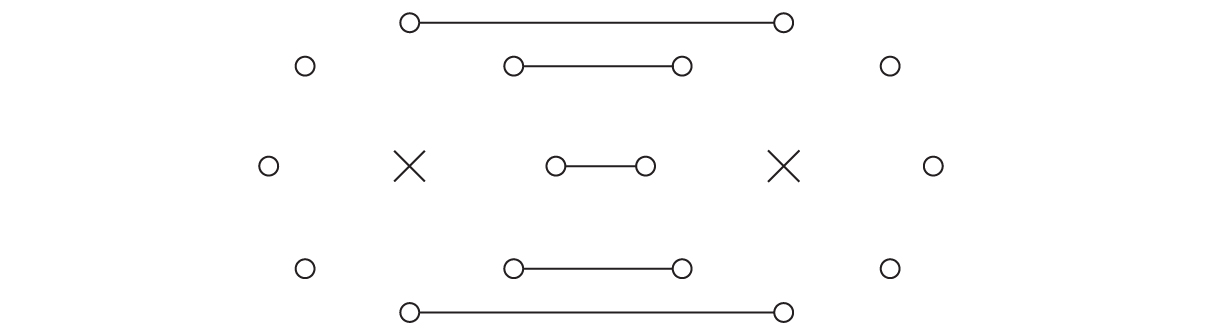

So, after those ten years and feeling squeezed in the form, I thought about doing a double profile, through a process like this:

In the resonance between the two sides, added dimension might develop. Maybe I would twice meet myself coming the other way. Or four times. Who could tell what might happen? In any case, one plus one should add up to more than two.

Then who? What two people? I thought of various combinations: an actor and a director, a pitcher and a manager, a dancer and a choreographer, a celebrated architect and a highly successful bullheaded client, 1 + 1 = 2.6. One day while I was still undecided, I happened to watch on CBS a mens semifinal in the first United States Open Tennis Championships. Two Americansone of them twenty-five years old, the other twenty-fourwere playing each other. One was white, the other black. One had grown up beside a playground in inner-city Richmond, the other on Wimbledon Road in Clevelands wealthiest suburb. On their level are so few tennis playersand the places they compete are so organized nationallythat these two would have known each other since they were eleven years old. For something like three weeks, I kept thinking about that combination and its possibilities, and then decided to attempt a double portrait, letting the match itself contain and structure the story. I would not be able to do that without a copy of the CBS tape. In those days, tapes were not archived. They saw repeated use. The copying would have to be done as something called a kinescopea sixteen-millimeter film shot from a television monitor. I asked William Shawn, The New Yorker s editor, if he would pay for the kinescope. Very well, he said, sighing. Go ahead. I called CBS. A guy there said, You havent called a minute too soon. That tape is scheduled to be erased this afternoon.

Called Levels of the Game, the double profile worked out, and my aspirations went into a vaulting mode. If two made sense, why not four people in one complex piece of writing? That was when I put the block letters on the bulletin board. A, B, and C would be separate from one another, and each would interact with D, yes, but who were these people? As things would eventuate, the two projects I am describing1 + 1 = 2.6 and ABC/Dwould be the only ones I would ever do that began as abstract expressions in search of subject matter. Quoth the raven, Nevermore. Meanwhile, there was still no theme for the quadripartite profile. What to write about?