Published in the UK in 2012 by

Corinthian Books, an imprint of

Icon Books Ltd, Omnibus Business Centre,

3941 North Road, London N7 9DP

email:

www.iconbooks.co.uk

Previously published in 2010 by Integr8 Books

This electronic edition published in the UK in 2012 by

Corinthian Books, an imprint of Icon Books Ltd

ISBN: 978-1-906850-27-2 (ePub format)

ISBN: 978-1-906850-37-1 (Adobe ebook format)

Sold in the UK, Europe, South Africa and Asia

by Faber & Faber Ltd, Bloomsbury House,

7477 Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DA or their agents

Distributed in the UK, Europe, South Africa and Asia

by TBS Ltd, TBS Distribution Centre, Colchester Road

Frating Green, Colchester CO7 7DW

Published in Australia in 2012

by Allen & Unwin Pty Ltd,

PO Box 8500, 83 Alexander Street,

Crows Nest, NSW 2065

Distributed in Canada by

Penguin Books Canada,

90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700,

Toronto, Ontario M4P 2YE

Text copyright 2010, 2012 Michael Calvin

The author has asserted his moral rights.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, or by any means, without prior permission in writing from the publisher.

Typeset in New Baskerville by Marie Doherty

For: My Family.

Thanks for yesterday, today and tomorrow.

About the author

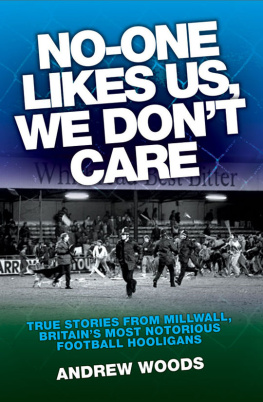

Michael Calvin is one of the UKs most versatile sportswriters, having feigned expertise in everything from frog jumping to Aussie Rules football. He has worked in more than 80 countries, covering six summer Olympics and six World Cup finals. He was named Sportswriter of the Year for his despatches as a crew member in a round-the-world yacht race. He has twice been named Sports Reporter of the Year, has featured in the British Press Awards on four occasions, and has won awards for his coverage of sports for the disabled. He established a global reputation during a decade as chief sports writer with the Daily Telegraph, and has held similar positions at The Times, Mail on Sunday and Sunday Mirror. He took a five-year sabbatical from journalism to help set up and run the English Institute of Sport, which offers strategic support to 35 Olympic sports. When asked by Kenny Jackett what possessed him to choose Millwall as the subject for this book, he admitted: I thought it was worth a punt. Jackett laughed and said: Some punt. Some season

www.michaelcalvin.com

Contents

Chapter 1

Family Ties

The knife penetrated Alan Bakers ribcage, in the fourth intercostal space, just beneath the right nipple. It sliced through veins, nerves, and arteries, puncturing a lung. His breath came in short, searing bursts, and he suffered severe blood loss, but he was lucky. Had the blade been wrenched to the left, instead of the right, it would have hit his heart. The officer from the Police Support Unit, who helped save his life after he had stumbled through an alleyway before collapsing outside a bus garage 300 yards from Upton Park, would have been a coroners witness. His assailant, hidden in a melee of at least eleven attackers, estimated by police to be aged between their early twenties and mid-forties, would have been the central character in a murder inquiry.

The hunt was conducted, with feral efficiency, just after 8.00pm on what the headline writers designated, with a tiresome lack of originality, as footballs night of shame. Only the dates in this case Tuesday 25 August 2009 change. The themes of social dysfunction, institutional arrogance and ritual criticism are constant. Baker was a Millwall season ticket holder, a former fireman of impeccable character who was systematically separated from nine members of his family as they attempted to reach the second round Carling Cup tie at West Ham. The rumour that he had died, given credibility by the sinister atmosphere of choreographed violence, swept through the ground. The following day, Neil Harris, his idol, was at his hospital bedside.

Harris, scorer of Millwalls goal in a 31 extra-time defeat, was shocked to discover the victims identity. He had met Baker during a holiday in Portugal that summer. They had shared ice cream, discussed football folklore and the common challenges of family life. As the teams spiritual leader, Harris led them off during the second of three pitch invasions, when a youth ran across his path and drew his hand across his throat in an unmistakable mime of malevolence. He was as scared as he had been during an exemplary career, which had entered its thirteenth season. Its the only time I have ever felt threatened on the pitch, he admitted. Anyone could have walked past, slashed the back of your leg with a knife, or worse. You are basically putting your fate in the hands of idiots. Youre hoping they are not mad enough to do you harm. During the initial invasion, when he was abused as a fucking wanker and Millwall scum, he had been able to smell the alcohol on fans breath. Local pubs, and bars serving home fans at the ground, had remained open, despite warnings.

In the circumstances, no one gave a thought to Kenny Jackett, the Millwall manager, who considered the scenes the worst he had witnessed in 32 years in football. He had only three outfield players as substitutes, and compiled his game plan from a borrowed DVD and a single scouts report compiled by Steve Jones. It was a masterpiece of economy and tactical insight, almost too good for the common good. Jackett had spotted West Hams limitations out of possession, their reluctance to track laterally, as Gianfranco Zolas system required. He had recognised the potential of exploiting one-on-one situations in wide areas. His preparatory work, on the training ground, took Millwall to within three minutes of a victory that would have caused even more bloodshed.

Ken Chapman, Millwalls security and operations advisor, believed the match finished only because of West Hams 87th-minute equaliser, a Julien Faubert cross swept in by Junior Stanislas. The goal prompted the first incursions, and quelled, temporarily, the pitched battle between home fans, stewards and police, which was building to a crescendo in the north-west corner of the ground. Chapman, who spent 33 years in the Metropolitan Police, the last five as borough commander in Lewisham, was monitoring events at home with an air of foreboding, sadness, and exasperation. His sense of duty was offended.

He shared intelligence, but had been excluded from the planning process by West Hams Safety Advisory Group, which comprises club officials, police representatives, and assorted bureaucrats. Chief Superintendent Steve Wisbey had been involved in policing football matches for 29 years, but was in his first season as match commander at Upton Park. He was dismissive of Millwalls protests about being limited to 2,300 tickets, less than half of what they were entitled to under competition rules. He gave more weight to the advice of Louisa Elliston, a functionary from the Football Licensing Authority. Chapmans fears of problems created by ticketless Millwall fans were realised when between 200 and 300 gained entry to the away end, little more than three minutes after kick-off. Initial reports that they had stormed an exit gate were clarified by CCTV footage, which revealed a white-coated steward opening the door, outwardly. It took precisely 80 seconds to herd them into the lower tier of the Sir Trevor Brooking Stand.