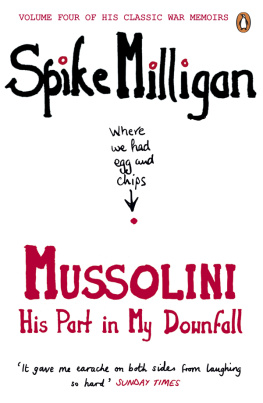

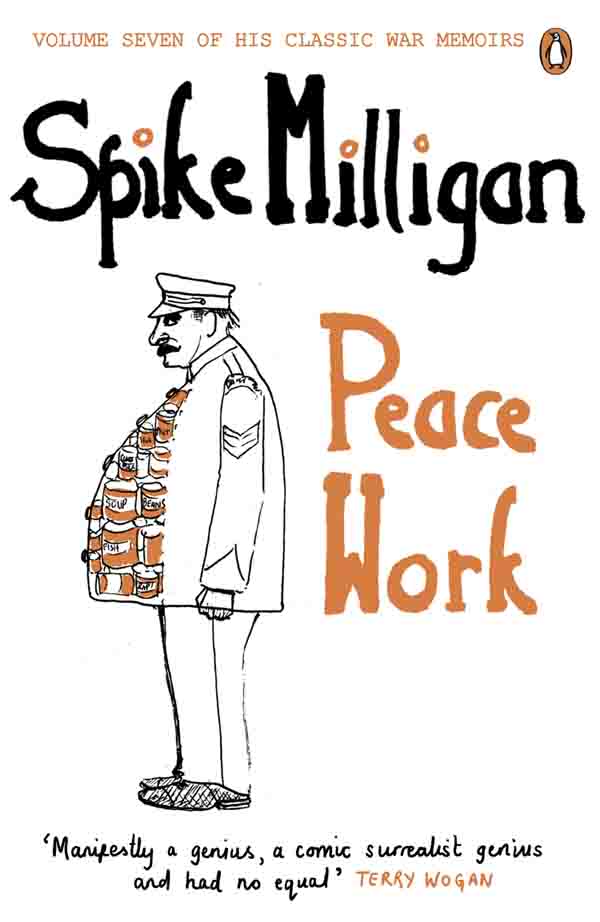

PEACE/WAR AUTOBIOGRAPHY VOL. 7

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, Block D, Rosebank Office Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North, Gauteng 2193, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

www.penguin.com

First published by Michael Joseph 1991

Published in Penguin Books 1992

Reissued in this edition 2012

Copyright Spike Milligan Productions 1991

All rights reserved

ISBN: 978-0-24-196621-1

PENGUIN BOOKS

PEACE WORK

Spike Milligan was one of the greatest and most influential comedians of the twentieth century. Born in India in 1918, he was educated in India and England before joining the Royal Artillery at the start of the Second World War and serving in North Africa and Italy. At the end of the war, he forged a career as a jazz musician, sketch-show writer and performer, touring Europe with the Bill Hall Trio and the Ann Lenner Trio, before joining forced with, among others, Peter Sellers and Harry Secombe, to create the legendary Goon Show. Broadcast on BBC Radio, the ten series of the Goon Show ran from 1951 until 1960 and brought Spike to international fame, as well as to the edge of sanity and the break-up of his first marriage. He had subsequent success as a stage and film actor, as the author of over eighty books of fiction, memoir, poetry, plays, cartoons and childrens stories, and with his long-running one-man show. In 1992 he was made a CBE and in 2001 an honorary KBE, and in 2000 and 2001 he received two Lifetime Achievement Awards for writing and for comedy. He died in 2002.

Home

Indeed, we won the war, but I lost five precious years. I was to mourn and still do, the physical break-up of my family; it was a sort of time-warp Belsen. As my ship left Naples harbour it was the cool end of autumn the year 1946; time, like the ship, was slipping away, an azure twilight glazed the Campania, lights enumerated along that seemingly timeless shore, now lifeless, Vesuvius was turning into a faded amber silhouette. I stood aft on the promenade deck, seamen still fussed around the ships limits, other passengers leaned out at the rail. I watched the oncoming pollution, as they tossed their cigarette ends in the sea.

Goodbye, here was I saying Goodbye to all that though I was only twenty-eight, here I was saying goodbye, I hated goodbyes, they gave me the same haunting sadness every time. Wherever I had put down emotional roots, it was painful to bid it adieu; I am still haunted by all the homes I have had to leave. What was it like to live in a cottage in a village in the sixteenth century, and never say goodbye to it? Is the modern social pattern of unending change and movement the cause of two modern diseases, insecurity and dissatisfaction? How lucky Thomas Hood was to be able to write:

I remember, I remember,

The house where I was born.

I dont even know what mine looked like! I stayed on deck, smoked a Capstan full strength, one of my last NAAFI-issue cigarettes. On the portside, we passed what were then isles of magic memory, Capri and Ischia, scarlet and bronze in the sunset; the sea was turning to ink, our propellers churning up a Devonshire cream wake, the ships siren sent out a long mournful departure note it echoed across the bay.

Eddy Molloy, who had been below, joined me; hed run out of cigarettes, sure enough, Ive run out of cigarettes, he said. In the Central Pool of Artists he had been known as Virgin Pockets as no human hand had ever entered there for money. Ashore, somehow he had the franchise for the weekly NAAFI Ration. He would sell anything, half of Italy was walking the streets in overcoats made from his army blankets. When asleep, one only had to whisper How much? in his ear, he would leap to his feet and sell you his bed. Yes, Ive run out, he reconfirmed, puffing away; Ive got to cut down, on mine I hoped. Its getting chilly, he said and all his blankets ashore. Ive got a nice cabin, he said. I waited for him to sell it to me. It was dark, better go below before he sells me a torch.

The four-tone dinner xylophone had gone, First dinner sitting, called the white-uniformed steward.

Im first sitting, said Molloy, referring to his seating card.

Good, I was second sitting.

Why dont you change to first? he said. No, wait, Ill change to second.

So while I waited he did. We sat at the pursers table, or was he sitting at ours? Mr Greenidge. Yes, twenty years with P & O and Union Castle, nearly torpedoed twice. He was a man in his middle fifties, or a woman in her late sixties, a repressed homosexual with a wife and one daughter. He was possibly the first human gynandromorph.

Next to him, Eileen Walters, Queen Alexandra Nursing Sister a fine, cheery, plump, sweaty matron, passing forty, at great speed, and mostly uphill. I came out via the Cape, on the er the er. Oh dear, she cant remember. Never mind, she came out on the SS The-er.

Two officers at the table, one in mufti, Carlton Death, tall in a rigid Eiffel Tower way, saturnine, his jet eyes incredibly close together, a forceps delivery Id say. Before we had finished soup, he let slip he was Coldstream Guards and ex-Eton. I heard myself saying I was a Lance Bombardier and ex-Brownhill Road School, Catford, Not many people can say that, you see the school burnt down, I concluded.

There was Captain Manning OBrien, a wayward romantic Irishman, who had produced some of our shows at CSE Naples; how does a man who claims he was dropped with fellow drunk Randolph Churchill into Yugoslavia to organise Titos guerrillas and Alcoholics Anonymous get posted back to an entertainment unit and Alcoholics Anonymous? His first effort was to call a parade. Any Irishmen here? he said. Two of us held up our hands. You four step forward, he said. We need schum more hic, he shed. It was only 8 a.m. His show, Shamrock Review, was unbelievable. The entire cast were untrained Italian POWs. Their sallow complexions done over with a pale make-up, red lips, pink cheeks and the occasional red wig, each one dressed in green breeches smothered in red shamrocks (red?). Every victim had been taught the songs parrot-fashion. The curtain went up on a tableau of an Irish village, harps, jaunting cart, shillelaghs, and the opening chorus Begin The Beguine. Efforts had been made to parachute him back to Yugoslavia, or Greece, or anywhere. He ordered drinks for the table, and I think for the chairs as well. God, you should have seen Tito and Randolph together, he said. I said how sorry I was not to have.