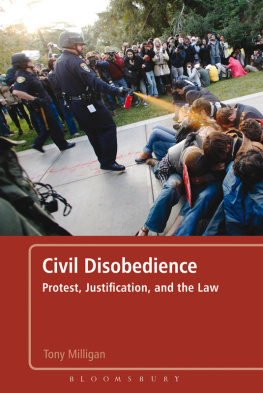

Civil Disobedience

Protest, Justification, and the Law

Tony Milligan

Bloomsbury Academic

An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

175 Fifth Avenue | 50 Bedford Square |

New York | London |

NY 10010 | WC1B 3DP |

USA | UK |

www.bloomsbury.com

First published 2013

Tony Milligan, 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers.

No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury Academic or the author.

ISBN: 978-1-4411-2676-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Milligan, Tony.

Civil disobedience : protest, justification and the law / by Tony Milligan.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4411-1944-5 (hardcover : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-1-4411-3209-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Civil disobedience--United States. 2. Civil rights--United States. I. Title.

JC328.3.M55 2013

303.6'10973--dc23

2012036379

Typeset by Fakenham Prepress Solutions, Fakenham, Norfolk NR21 8NN

To Suzanne, for showing me a gentler strength.

CONTENTS

Civil disobedience has become an endangered concept. Or at least that was the case until a wave of mass non-violent dissent hit North Africa, parts of South-West Asia, Western Europe and North America during 2011, raising all sorts of issues about how to understand contemporary political unrest as well as bringing the legitimacy of economic and political institutions into question. Even at the time, an obvious case could be made for regarding a large number of the protests as civil disobedience, but some commentators were cautious about doing so. They raised concerns about the relevance of the very idea of civil disobedience to something so new and so radical. In the course of this book I will attempt to allay these fears and to show that claims of civil disobedience have a vital, forward-looking role to play. Moreover, they can defensibly be made about a wide range of actions including many of those carried out by participants in the Occupy Movement in America and Western Europe. This opening chapter will be given over to a narrative account of the latter. My undisguised determination to vindicate the relevance of civil disobedience may, however, raise some concerns about the narrative, about the possibility that it could be skewed to support my overall conclusion. Like all such narratives of dissent, it may be challenged in point of detail and interpretation. There is, after all, a gap that invariably opens up between protest on the ground and subsequent reportage. Nonetheless, what follows is an outline of events that should be recognizable to participants and recognizable also to the vastly larger number of sympathetic onlookers whose connection to events was primarily through the popular media. In places, it may also capture a sense of the excitement of the moment.

Zuccotti Park

Between May and December 2011 public squares in Europe, parks in the US and even the precincts of St Pauls Cathedral in London were occupied. Demonstrations in some of the worlds major cities took place on a scale that had been unknown for decades. At its height, the international focal point for this movement was the Occupy Wall Street camp in Zuccotti Park, a 33,000 feet-square area of ground in Lower Manhattan that was once, appropriately, called Liberty Plaza. Located only a block away from the site of the former World Trade Center, Zuccotti is a highly symbolic space. Its occupation in September 2011, only a week after the anniversary of the 9/11 attacks, might have struck a more cautious or leadership-dominated movement as an unnecessary and provocative risk.

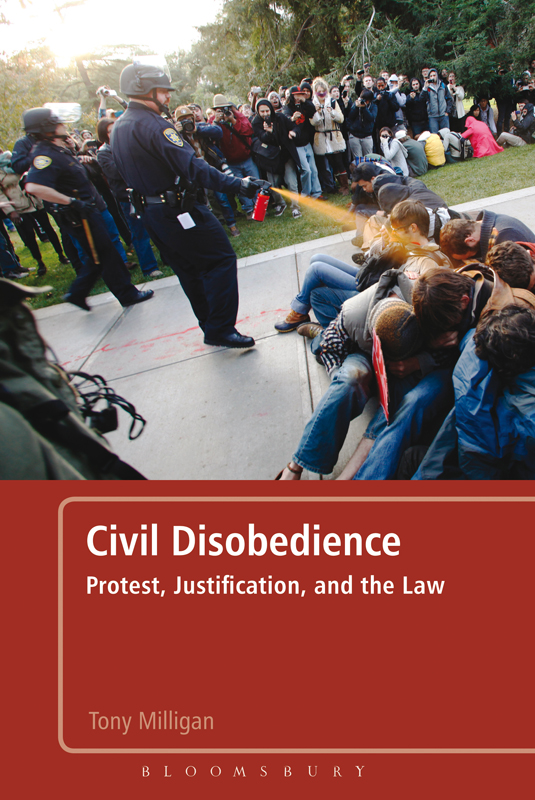

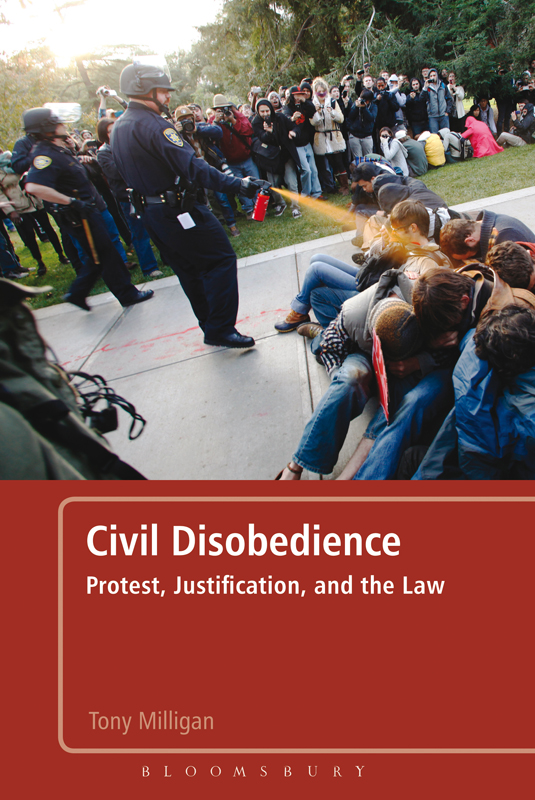

Zuccotti became the focal point by accident rather than design. The occupiers had considered elsewhere. There was talk about a small group trying to occupy the J. P. Morgan building, One Chase Manhattan Plaza, but the Park was more accessible, more public. At first the numbers were small; a couple of hundred protestors camped out by night and slightly larger numbers blocked traffic by day in an attempt to publicize their cause. The police responded with familiar tactics for urban control. Protestors were subjected to kettling, the forcible division of crowds into easily controllable groups followed by the immobilizing confinement of each group, often behind a wall of police officers wielding riot shields. Pepper spray, derived in part from capsicum chillies, was used to facilitate the process. Its use in civil disturbances is not unlike the herding of cattle as they are prodded to go first one way and then another. The impact of the spray can be both physical and moral. It disables individuals and can convince others that they face an overwhelming obstacle. Its use against the protestors in New York had the former impact but not always the latter.

Regularly used in the US since the early 1990s, the spray was first introduced as a way of applying non-lethal force in situations where immediate self-defense or the defense of others might be required. In practice, it has become a favored device of control, a ready multi-tasking solution in a can. It has been used with some regularity to force eco-protestors to unlock themselves from secured positions and, more controversially still, in combination with hoods and control chairs, against problem prisoners in correctional and custodial facilities. As a chemical agent, its use in warfare is illegal under international law. Within the US, state legislatures have differed about how it may reasonably be used. Protestors and legal counsel complain about the spray and some legislators accept that they have a point. If its use would be illegal on a battlefield, there is a question about why it should be considered legal on the streets.

Against the Occupy Wall Street protestors, video footage indicates that pepper spray was used in situations where there was clearly no threat, a

Buoyed by the combination of illegal protest and the largely peaceful occupation of public spaces, the movement spread nationally and internationally. By the end of October, a month after Occupy Wall Street protestors first moved into Zuccotti, there were an estimated 2,300 occupied zones in 2,000 cities worldwide. In London, matters were on a smaller scale. The focal point was a tent village set up just below the steps of St Pauls Cathedral in London. The protest camp was, nonetheless, given daily television coverage while church authorities argued over the respective merits of having the protestors removed by force or washing their hands and passing on the decision to Westminster City Council .

Then came the reaction. An international process of clearance began at the end of October with the forcible removal of the tents in Victoria Park, Ontario. A brief pause followed to avoid the potential flashpoint of Guy Fawkes night, then the curfews and forcible clearances resumed. Some of the camps were able to mount legal challenges, and some were too small to be dealt with in the first wave of removals. But key sites such as Zuccotti and Oakland were cleared, amid scuffles, arrests, attempted reoccupation and the ongoing use of pepper spray to control the predominantly non-violent but now clearly angry protestors. A striking feature of the movement, from the outset, was this ability to remain largely (but not exclusively ) non-violent. Yet the participants in the Occupy Movement also exhibited a strong degree of ideological continuity with the anti-capitalist protesters who had forcibly taken over the streets of Seattle a decade earlier. Both established ground-level assemblies, institutions of direct democracy which were then contrasted with a hierarchical and compromised state-run democracy. Both involved an avoidance of formal leadership, a rejection of the idea that movements need charismatic figureheads who can enter into negotiations on their behalf.

Next page