1

I T WAS A CHILD , screaming in nightmare, which awoke me. As I rose from the depths of my sleep, sluggishly, like a diver surfacing from the seabed, the corridors of the hotel echoed with those pealing, terrified cries. They poured over the balcony beyond my room and filled the courtyard beneath; they streamed out into a town which was cooling itself, ankle-deep in sand under a new moon, and they were lost, plaintively, among the low dunes scattered to the south and to the east. I reached consciousness to the dimmer sound of a fathers voice gentling the infant terrors away, and the night became stealthy with silence again. But the spell of tranquillity had been broken. In a day or two I must leave this room, with its bare security and comfort, and move off into those dunes beyond the mosque, into the awful emptiness that stretched for three thousand miles and more to the east. A man called Mohamed was even now travelling down from his encampment in the desert, to be my companion at the beginning of what seemed to me a very fearful journey.

I, who normally sleep so securely that I have rarely been able to recall my dreams on wakening, had experienced the childish nightmare too, in the past few months. There had been a midsummer night in London when I had dreamt myself deep into the Sahara, among endless sand dunes and a formless, panic-stricken sense of being lost and in peril. I could not tell whether I had failed to find a vital water hole, or whether I was just hopelessly unable to decide which way I must go to safety; the images were inexact, only the torment was penetratingly clear. As I emerged from the horror of it, my body streaming with sweat, my mouth bitterly dry, the woman I loved helped me to safety again.

But now, in this room on the edge of the desert, there was no A to calm my fears. Nor were the fearful images inexact any more. For two or three weeks I had prowled around this rim of the Sahara, preparing myself for my journey. I could visualise its beginning with some clarity, and I now had the name of a companion to give a tiny substance to any event my imagination conjured up. As the childs screams dwindled into sobs and died with a whimper, I lay blankly and widely awake for a while. A couple of dogs barked down by the marketplace, where all the commerce of Islam heaved and badgered and bartered during the day. Then silence and nothing, nothing, nothingness stretching away to infinity around my room. On one side there was an infinity of ocean, on the other three an infinity of desert, all threatening this small remnant of civilisation which man had contrived against nature. What a folly it seemed to abandon that so wilfully.

Gradually, the images crept out of the corners of the room and shaped themselves over my bed. I saw myself asleep somewhere out in the nothingness, then wakening suddenly at some sound. Appalled, I saw that Mohamed was carefully leading our camels away. I was unable to move or call out from my sleeping bag, so transfixed was I by the care he took not to disturb me: he walked them down to the far side of the sand dune before mounting so that I shouldnt hear their protesting noise. By the time Id struggled out of my bag, hed vanished, with the camels, our water and our food. I had nothing but a sleeping bag and the dying embers of our campfire.

The sequence ended abruptly there. I shifted uneasily, aware that the blood was pumping through my chest more obviously than is normal at two oclock in the morning. Then another image crossed my mind. Again I was awakened from sleep in the desert, but this time Mohamed was inert in his blanket nearby. Cautiously I raised my head and saw figures creeping towards us, evidently bent on murder. As one of them approached my companion, I scrambled out of my sleeping bag, kicked Mohamed awake and leapt towards the attacker, my sheath knife already drawn and in my hand. Untidily, the sequence dissolved with me rushing up a dune, pursued by a figure. I stumbled and saw his weapona sword, a club or a knifedescending. Then the vision was gone. Much gratified as I was that my fanciful response had been so heroically in the best white mans tradition, I was nevertheless left pondering for several minutes just how I would get out of my sleeping bag in such an emergency, and whether, indeed, I ought to sleep with my knife quite ready for action of that sort.

Impatient by now of these midnight movies, I switched on the light and, reaching for Solzhenitsyn, began to read myself into torpor again. But my body, I noticed, had become a little clammy, though the night was cool. I was afraid.

*

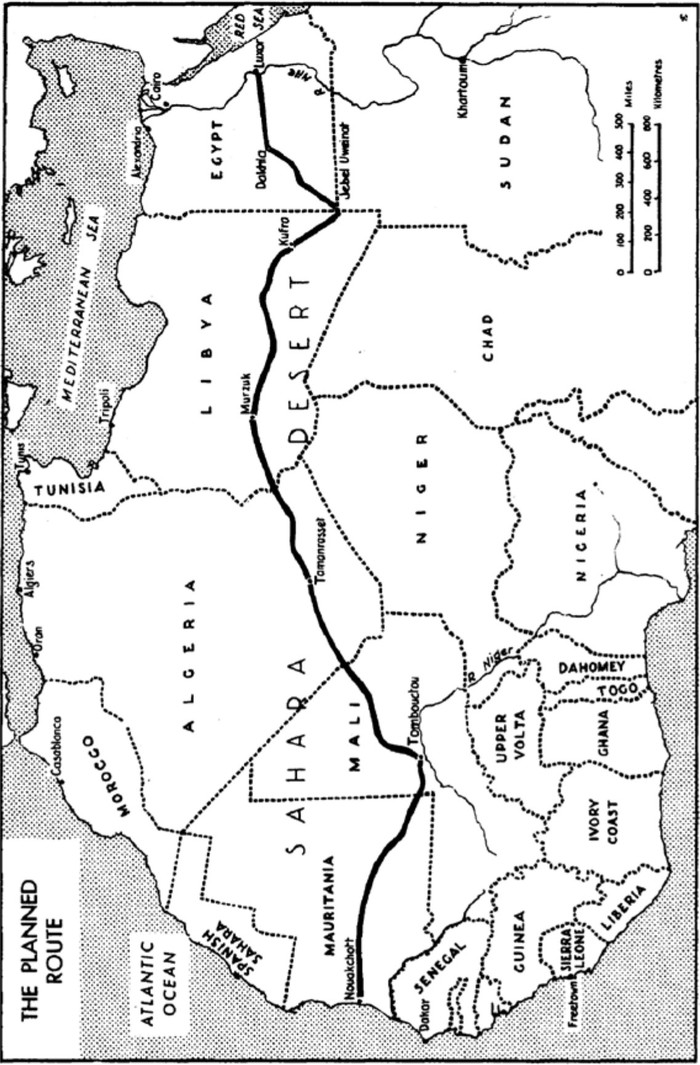

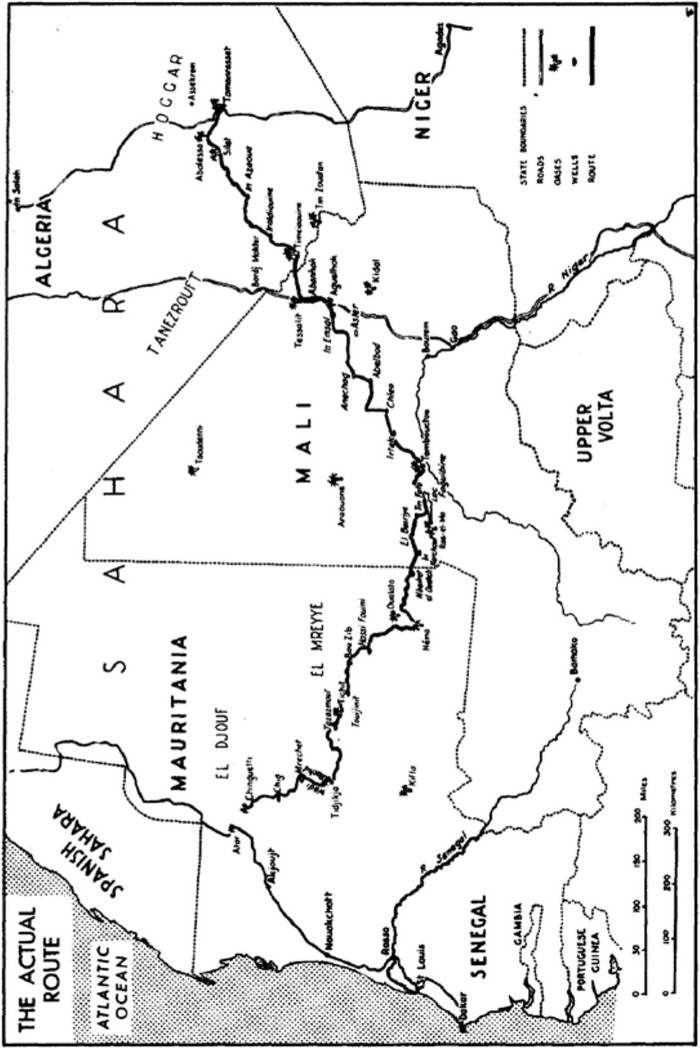

It was because I was afraid that I had decided to attempt a crossing of the great Sahara desert, from west to east, by myself and by camel. No one had ever made such a journey before, though many men have traversed the desert from north to south. For ages before Europeans ventured into the interior, there were well-defined caravan routes from Black Africa below the Sahara to white Africa fringing the Mediterranean. Slaves were regularly herded chiefly to find out what truth there was in rumours that here was a fabulous city on the southern edge of the Sahara. The motives of such men were always strongly seasoned with a taste for adventure on its own account. But always there was also the possibility of some tangible achievement at the end of their quest; and always this logically meant a crossing from top to bottom of the Sahara. There was never any logic to a journey made from the Atlantic to the Nile, or vice versa. The intervening space had gradually been known from the time of Herodotus to consist of nothing but sand, rock and diminishing savannah. The limits could easily be explored from the sea. The only lateral caravan routes in the Sahara were over relatively short distances, like the one from Agades to Bilma, for the conveyance of salt. There was only an adventurous challenge in trying to cross the biggest desert on earth between its most distant boundaries. Men ignored it until 1963, when a party of twelve Belgians with half a dozen vehicles motored from the Atlantic coast of Morocco right across to the Red Sea.

If I managed to make the first great traverse by camel, I would enjoy my success. I recognised that the moment I first thought of attempting the journey. In the spring of 1971, I was flying home from Sierra Leone at the end of some fieldwork for a book on nineteenth-century missionaries , with vague plans for a later history of Saharan exploration swilling round my head. It was a thick, muggy day as we took off from Freetown, and we were soon riding high above continuous banks of grey cloud. After an hour or so, this changed dramatically. The earth beneath was now hidden under a vivid orange fog. Whether it was a sandstorm or merely the colour of the desert reflected onto cloud, I had no means of knowing. But certainly it was the Sahara. And this orange pall covered the earth as far as the eye could see from thirty thousand feet. It was the first time that the terrible immensity of that wilderness had been registered on my emotions rather than my intelligence . Three and a half million square miles of desert at once became a staggering reality, instead of a statistic paraded before the bored glance of a mathematical ignoramus.

My emotions produced two responses, in quick succession . First there was an almost sensuous thrill of anticipation ; impulsively, I wanted to grapple with the void down there, I wanted to plunge into it, I wanted to stretch myself out to its limits. Instantly, my heart and my body recoiled from the prospect. I have climbed and walked among mountains since my school days, but still I have only to look at the photograph of a climber on some awfully exposed slab of rock, and the palms of my hands become damp with sweat. They became damp now, even as another part of me was seriously beginning to wonder whether I could possibly commit myself to the desert. I was aware that it had not been crossed the long way by one man using the deserts most primitive and traditional form of transport. The fantasy of such an achievement danced into already mixed feelings. Of one thing at least I was certain. I should relish that crown.