WHEN THE SAHARA WAS GREEN

WHEN THE SAHARA WAS GREEN

HOW OUR GREATEST DESERT CAME TO BE

MARTIN WILLIAMS

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON & OXFORD

Copyright 2021 by Princeton University Press

Princeton University Press is committed to the protection of copyright and the intellectual property our authors entrust to us. Copyright promotes the progress and integrity of knowledge. Thank you for supporting free speech and the global exchange of ideas by purchasing an authorized edition of this book. If you wish to reproduce or distribute any part of it in any form, please obtain permission.

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

ISBN 9780691201627

ISBN (e-book) 9780691228891

Version 1.0

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Ingrid Gnerlich & Mara Garca

Production Editorial: Ali Parrington

Text and Jacket Design: Karl Spurzem

Production: Danielle Amatucci

Publicity: Sara Henning-Stout & Kate Farquhar-Thomson

Copyeditor: Karen Verde

Endpapers, inside front cover: Map of major Saharan localities; inside back cover: Map of Saharan and adjacent countries

In memory of Franoise Gasse, Thodore Monod, and Pascal Lluch: You shared my love and respect for our greatest desert. Valete!

CONTENTS

- ix

- xvii

- xxv

ILLUSTRATIONS

Maps

Figures

Tables

Plates

PROLOGUE

An Isolated Mountain

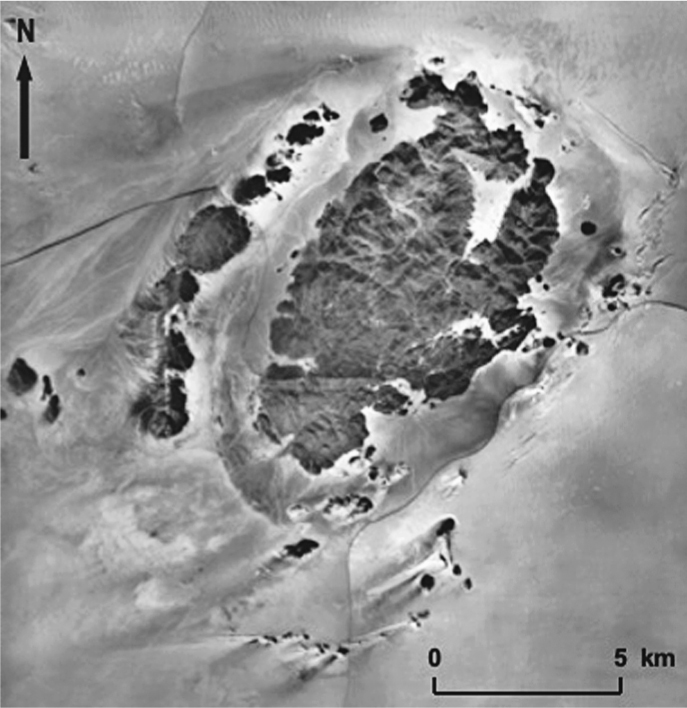

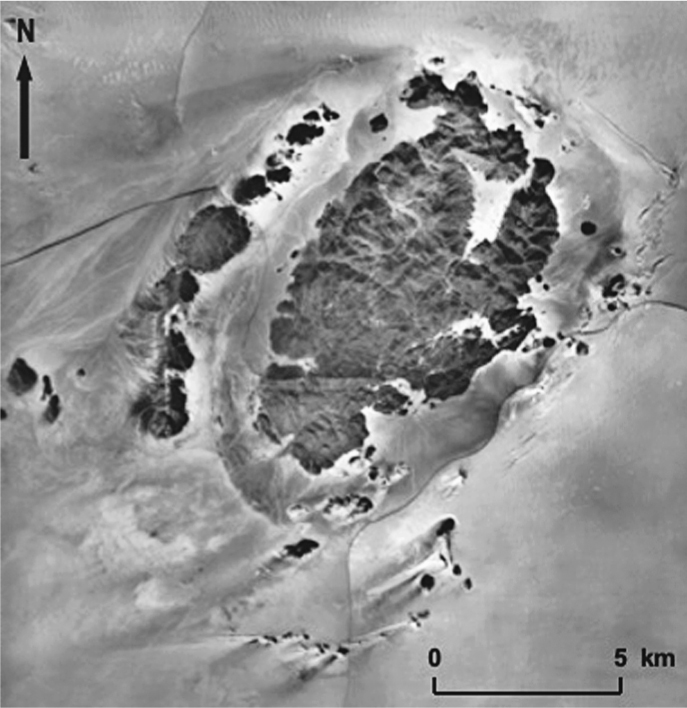

Just after dawn in late March 1970, two men were walking slowly alongside the ancient shoreline (). It was surrounded by rolling sand dunes and undulating sandplains and, lacking water and being mostly devoid of vegetation, was uninhabited.

One of the men, Professor John Desmond Clark, was a distinguished archaeologist at the University of California, Berkeley. The younger man was the author, who had been a professional soil surveyor mapping soils along the lower Blue and White Nile valleys in Sudan. The previous night had been very windy, blowing highly abrasive sand grains across the surface of the now dry lake. The lake sediments consisted of easily eroded fine silts. What the nights sandstorm had revealed was the rib cage of a long dead hippopotamus. Even more exciting was what was embedded in the rib cage of the hippo: a barbed bone harpoon point. The two men looked at each other. They agreed: This one stays. Desmond and I had just completed three months of archaeological excavations and geological mapping and sampling, and this was our last day at Adrar Bous before the long journey back to California for Desmond and his archaeological team and to Sydney, Australia for me.

FIGURE P.1. Adrar Bous seen from the air. Photo mosaic compiled by the author from air photos. IGN, National Photo Library.

This chance discovery reminded us of another lucky find three months earlier, on our very first morning at Adrar Bous, when we were the two first members of our team to reach the mountain. Once again, it was an early morning walk, as we began to familiarise ourselves with what was to be our home for the next twelve weeks. Just as the sun rose, a tiny piece of what looked like white bone caught the light. The bone was embedded in a very hard, dark grey clay. The bone was in fact a horn-core. Later painstaking excavation with dental picks revealed the entire skeleton of what turned out to be the oldest complete domestic cow ever recovered from the Sahara. It proved to be about 5000 years old.

It was entirely by accident that we were to spend three dry and windy months at the isolated mountain of Adrar Bous. If you draw an imaginary circle of 1500 kilometres (or nearly 1000 miles) radius, with Adrar Bous at the centre, the circle rim will only intersect the Mediterranean coast of North Africa and the Atlantic coast of West Africa. At Adrar Bous, you are about as far inland as it is possible to be in North Africa, which is one reason why it is so dry. The summer monsoon rains seldom reach this far north; the westerly winter rains seldom reach this far south. Even if they did, by then they would have already lost most of their initial moisture supply so that not much rain would fall. As a general rule, the further inland you go, the drier it becomes, an effect known to climatologists as continentality. So, why did our team choose Adrar Bous as its destination?

Revolution and a Change of Plans

Our initial plan had been to continue our earlier work in Libya in the southeastern Libyan Desert. In the course of two summer expeditions there in 1962 and 1963 led by Captain David N. Hall, a young British army officer with the Royal Engineers, we had made some exciting discoveries. Our first summer was spent at an isolated mountain in the far southeast of the desert known as Jebel Arkenu (). Here we had found many beautiful rock paintings and abundant evidence of prehistoric human occupation. The following summer we mapped and named two huge sandstone plateaux in the far south of the Libyan Desert. Once again, we noticed abundant signs that this now arid region had been occupied on several occasions by prehistoric people, from Early Stone Age times onwards, a lapse of time amounting to nearly a million years. As well as prehistoric stone tools, we saw numerous rock engravings and multi-coloured paintings of people and herds of domestic cattle which offer a glimpse into a way of life that is no longer possible in this now desolate and arid region.

In order to build on our previous work and desert experience, David had assembled a very capable team of people with a range of practical skills; he had invited archaeologist Desmond Clark to bring a small team of graduate students and included me to assist with studying the soils and the landforms. Most of our group were young army and navy officers, all of whom had recently completed a degree in engineering at my old University of Cambridge. We had our team, vehicles, and supplies ready to go when disaster struck. Colonel Muammar Gaddafi staged a coup, the Libyan Royal Family were forced to flee, and foreigners were no longer welcome.

By great good luck Desmond had met the French Saharan archaeologist, Professor Raymond Mauny, at a lecture in California. Mauny had suggested that Adrar Bous in the Tnr Desert () might be worth a visit, so that became our destination. A French expedition sponsored by the Berliet truck company had already spent some time there and had reported abundant surface finds of prehistoric stones and bones. However, said Mauny: There is no stratigraphy! By this he meant that all the material was on the surface, having been concentrated by the combined work of wind and water, so that nothing was in its original position. From a scientific perspective, this meant that little of archaeological value could be culled from the surface finds. Fortunately, Desmond was not put off by this pessimistic verdict, and our later excavations were to prove it wrong. There was plenty of good, undisturbed material, provided you were willing to dig for it, which we did, for many weeks.